Their Solution (Formula, Part 1)

The evolution of the Beach Boys' formula for success, 1961-63.

Several chapters in the History of Brian Wilson posting-series have concerned the Beach Boys’ “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” 45-rpm single, released in August 1964. (See Parts 23-26, and also here). Part 26 suggested that Capitol Records released “Little Honda” as a single in September (via Four by the Beach Boys) as a subtle corrective to Brian Wilson’s choice of “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man).”

Even if it wasn’t, Four by the Beach Boys at a minimum signified Capitol’s belief that “Little Honda” was singles chart material—and should be promoted as such. This little rift—Brian and “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” on one side; Capitol and “Little Honda” on the other—can be seen as an early manifestation of the famous “art vs. commerce” issue in Beach Boys history.1

Upon review, Part 26 was pretty cavalier with respect to various terms: “fad,” “formula” (or “formulaic”), “salesmanship,” “commerciality,” etc. The post says that the Beach Boys established an identity as a “surf/teen/fad band”—as if all those things were basically equivalent. But they’re not. As will hopefully become clearer by the end of this (two-part) post, Brian Wilson didn’t think they were the same.

Before moving forward with the next post in the History of Brian series, it probably would be a good idea to insert an Appendix post on the subject of “fad,” “formula,” and “teenage music.” The goal isn’t to provide a textbook definition of these concepts, but only to better clarify what the words mean when applied to Brian Wilson’s music and career with the Beach Boys.

Today, it is commonly accepted that a “Beach Boys formula” existed, which—at least among critics and a subset of fans—has come to be deplored. What the critics object to isn’t the musical part of the formula, for example the multi-part harmony vocals that often gave the records a distinctive and appealing sound. It is the group’s overall presentation—its stance, themes, and song concepts—that embodies “formula” in the negative sense.

As specifically applied to Brian Wilson as an individual distinct from the Beach Boys organization, the word formula has become an outright pejorative, owing to the commonly-held opinion that (1) Brian’s best and most sophisticated music deviated from formula; (2) in trying to make this kind of music, Brian faced opposition from his family, the other Beach Boys, and Capitol Records—which in turn means; (3) those parties obstructed and ultimately thwarted Brian’s effort to make great music. While this controversial issue does not come to the fore until sometime in 1966, it is already detectable in the opaque maneuvering surrounding “Little Honda” and the more unconventional “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man).”2

Figuring a way into the music business is not easy, and there shouldn’t be anything wrong with using a predetermined procedure—working like a set of instructions—to do it. (Just as there’s nothing inherently wrong with using a cooking recipe, medical prescription, mathematical theorem, statistical analysis, or computer programming algorithm to solve a difficult problem.) In the pre-Beatles world of 1961-63, it was very difficult to break in just by playing rock ‘n’ roll, in a band format with vocals and lyrics. (Rock instrumental groups were more in vogue.) Everybody, even Bob Dylan, needed some kind of hook.3 The Beach Boys found an effective and original formula (and it found them) that was theirs alone. They achieved success in the business as originals, not copycats following a template laid down by a preceding band.

If there’s a problem with the Beach Boys’ relationship to formula, it shouldn’t be formula per se—the original discovery of a “secret sauce” and its practical application. It is more likely the group’s failure or unwillingness to sufficiently separate itself from the original formula that puts people off. By the mid-1960s, the Beach Boys formula had arguably exhausted its usefulness, while Brian Wilson was—allegedly, and controversially—providing the group with better options.

Whatever it was that occurred between Brian and the Beach Boys at mid-decade (around the time of Pet Sounds, “Good Vibrations,” Smile, Smiley Smile, etc.) is one of the central issues of the entire Beach Boys Saga. For now, a different question: what, exactly, was the Beach Boys formula?

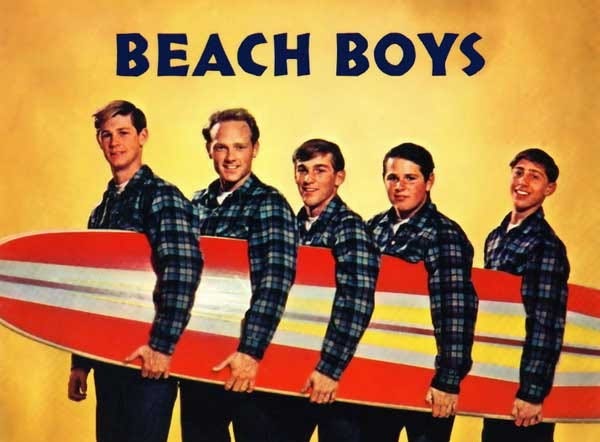

Although Dennis Wilson’s initial idea for a “song about surfing” was honestly rooted in his real-life experience as a teenage surfer, it had inherent commercial potential. Still, it wasn’t formulaic. Nor was Hite & Dorinda Morgan’s decision to publish the song “Surfin’” and find a label to put it out. That was just business. But when some record-biz guys refashioned the “Pendletones” as “Beach Boys,” a formula—a special combination of elements—was in the making: if a group is singing about going surfing, they should be called “Beach Boys.”

The boys didn’t like their new name, not necessarily because it was formulaic, but because it was goofy. But they came to accept it once they discovered that “Surfin’” was getting played on the radio. In their “Pendletones” guise, the group already had impressive musical (vocal harmony) talent, but that didn’t count for much. Being “beach boys” who sang about surfing was what got them into the business.

After “Surfin’” became a local hit, Brian Wilson and Mike Love took another step toward formula by “doing it again” and writing “Surfin’ Safari,” a vastly improved version of “Surfin’.” Brian then took up with Gary Usher, with whom he wrote a set of more generic teenage pop songs. Given what had recently transpired with “Surfin’,” Brian and Gary would have been justified in writing some zippy surf songs (besides the beach-ballad “Lonely Sea”). They didn’t. In retrospect, this indicates Brian’s ambivalence toward the idea that surfing or beach culture should be his primary, if not exclusive, subject matter.4

However, the Wilson-Usher tunes didn’t make it, while “Surfin’ Safari” stood out as the Beach Boys’ best and most commercially successful recording of 1962. Next, Brian went back and did it again once more with “Surfin’ U.S.A.,” the song through which the Beach Boys broke through nationwide. By embracing their identities as “beach boys” and singing three increasingly successful songs about going surfing, the Beach Boys became stars. The group’s name, combined with that initial sequence of surfing songs established a marketing concept, and in in the mind of the public, the Beach Boys’ raison d’être.

Perhaps that explains why, to this day, it’s commonly assumed that the Beach Boys formula required Brian to write songs “about the beach.” That was literally true only during a brief window of time, starting after Surfin’ Safari and the Gary Usher era, and extending through the first half of 1963, the period covering “Surfin’ U.S.A.,” the album of the same name, and the Surfer Girl album at mid-year. After Surfer Girl (released September 1963), the Beach Boys were basically done with the beach and surfing (though “summer” would remain a recurring theme).

In fact (as mentioned in Part 14), even before then, during the Surfin’ U.S.A. period of early 1963, Brian and the Beach Boys were already turning toward car songs, with Capitol’s blessing. It was late 1962 or early 1963 when Brian commenced a partnership with lyricist Roger Christian for the express purpose of writing car songs. As the successful B-side of “Surfin’ U.S.A.,” their early collaboration “Shut Down” pointed the way toward “Little Deuce Coupe” (successful as the B-side of “Surfer Girl”), Little Deuce Coupe (the album on which the Beach Boys firmly recast themselves as a car band), and ultimately, Shut Down Volume 2 at the beginning of 1964.

History now views “car songs” and “surf songs” to be fundamentally indistinguishable within the Beach Boys’ discography. While there was a distinction at the surface level—a beach song was about the beach and a car song was about a car—few would bother to delineate the surfing Beach Boys from the car-club Beach Boys. From a musical or stylistic perspective, there was no meaningful difference. Underneath, all these songs were alike, easily grouped together under one unifying principle: fad.

Click here to continue on the subject of fad (and “The Formula”), as the Beach Boys move from 1963 to 1964.

Part 26 could have better emphasized that Capitol released “Little Honda” via Four by the Beach Boys while “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” was still in play, climbing the charts. Capitol was aware that Beach Boys singles shouldn’t compete in the marketplace, but did it anyway, working around the conflict by conjuring a new, corporate/marketing fiction: because Four by the Beach Boys was a new format—the “space-age super single”—it was not a traditional A-side/B-side, and therefore not in competition with “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man).” In Billboard magazine, Capitol merchandising VP Brown Meggs claimed that Four by the Beach Boys would be only “complementary” and not competitive with the Beach Boys’ current albums and singles. (How was that supposed to work?) In all, it suggests that Brian’s decision to go with “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” (and/or give “Little Honda” away to Gary Usher) hamstrung the label, incentivizing this roundabout method of getting “Little Honda” out as a single (in substance) while presenting it (in form) as something other than a regular single.

This might not be accurate. A less cynical explanation for Four by the Beach Boys is that Capitol was merely trying to develop the concept previously seen on Four by the Beatles. Or Capitol came up with the strange “4 singles = 1 single” concept as an experimental new product (“New Coke”) and was merely testing it with the Beach Boys. Or maybe the company recognized that the Beach Boys had an abundance of singles-quality songs on their albums that were relatively unheard and under-exploited. Maybe the 4-in-1 concept was nothing more than an effort to get a return on those songs without releasing them as standard singles. (The real solution to this problem was for groups like the Beatles and Beach Boys to lead with an entire album as a musical statement instead just one song/single. According to the conventional narrative, this first began to happen with the Beatles’ Rubber Soul in late 1965.)

It should again be noted that the idea of a behind-the-scenes “Little Honda” vs. “When I Grow Up” switcheroo (and Capitol’s response) is conjectural. Still, as things shook out in August and September of 1964, it just looks strange: Brian went with a song that from a business standpoint was not the best choice, when a recognizably safer option was available. And then Capitol tried and failed to make something happen with that safer option. It appears that Brian gave priority to the “art” song over the “commerce” song—for the first time in his career, and when there was a material distinction between the two categories. On previous singles, art (creativity, craft, purpose) and commerce had always been aligned. The “Surfer Girl” single was particularly strong on art, but well-aligned with commerce too. There was no conflict. “Be True to Your School” was bad art but good (short-term) commerce—a very acceptable pairing in the record business. The “Ten Little Indians” single from 1962 was bad as both art and commerce. Again, no conflict—everybody, Brian included, could it agree it wasn’t good.

Dylan’s first album on Columbia Records in 1962 was mostly blues and folk-blues covers, and his first single, “Mixed-Up Confusion,” was rock ‘n’ roll. Neither made much of an impression, and Dylan didn’t establish himself until he turned toward folk, politics, protest, and lyrical poetry. Maybe it’s heretical to portray this move as Dylan’s “hook” but it turned out that way. For Dylan, folk-protest would become formulaic—which helps explain why it was necessary for him to move away from it. More on a Brian Wilson-Bob Dylan comparison when (if) we get to 1965 in A Book of Brian Wilson.

Brian Wilson and Gary Usher began their partnership before the Beach Boys signed to Capitol Records and became a going concern. When he first partnered with Usher, Brian was behaving like a free agent, and less like a member of an extant band. (And to his father’s chagrin). In those early months, it wasn’t preordained that Brian would soon be posing with a surfboard out with the family in Malibu for the Beach Boys’ first album on Capitol. (It only seems that way in hindsight.) This could account for the bizarre absence of surfing songs on a “Beach Boys” album titled “Surfin’ Safari”: when the time quickly arrived to record the album, what Brian had ready to go was stuff like “County Fair,” “Heads You Win—Tails I Lose,” and “Cuckoo Clock.” Still, the fact remains that Brian (i) could have written surf songs with Usher; (ii) had justification for doing so; and (iii) didn’t.