The recording and release of “I Get Around” precipitated a period of subtle creative transition for Brian Wilson, signified by the August 1964 single “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)”/“She Knows Me Too Well.” Preceding posts (here, here, and here) have dealt with the significance of these tunes in the overall context of Brian’s creative and personal development during the critical year of 1964. The introspection of “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” and the adult character of “She Knows Me Too Well” were appropriate to these times—during which surfing and car songs were becoming stale, the “British Invasion” was underway, and the Beach Boys had fired Murry Wilson as band manager.

If the new single indicated that Brian was going to “grow up” (as man or musician) did it mean the Beach Boys would necessarily do the same? Did Brian’s idea of maturity or “manhood” line up with that of his bandmates? Did growing up require the Beach Boys to dispense with some of the old themes that were unlikely to fit with Brian’s evolving conception of the group and its music? As discussed below, the answer to the last question appears to be yes—at least for a brief moment in the middle of 1964.

Part 26:

First released on August 24, 1964, “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” entered the Billboard singles chart on September 5, the same week the previous Beach Boys single, “I Get Around” (released back in May), made its exit. “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” momentarily became the sole Beach Boys record on the chart, but not the only Beach Boys song: during those weeks in September and October when “When I Grow Up” made its way into the Top 10, “Little Honda,” a Brian Wilson-Mike Love composition founded on the current popularity of Honda motor scooters, was also climbing up the chart—but as performed by a new group called the “Hondells.”

It wasn’t the first time another group scored a hit with a Brian Wilson song. The previous year, Jan & Dean had a No. 1 with “Surf City,” written by Brian and Jan Berry. But with “Little Honda,” circumstances were different, and maybe a little strange too.

On “Surf City,” Brian strayed from the Beach Boys to collaborate separately, as a writer, with Jan & Dean on a new song that never properly belonged to the Beach Boys. In contrast, “Little Honda” was not only written in-house by Brian and his fellow Beach Boy Mike Love (who received formal credit at the time), but also recorded by the Beach Boys, and then released under the band’s name as an album track on All Summer Long in July. Moreover, the Beach Boys’ version was easily superior to the Hondells’. It had better vocals and production, notable for its fuzzy, distorted guitar and the classic Phil Spector-styled “Wall of Sound” effect.

Yet it was the Hondells, not the Beach Boys, who took “Little Honda” all the way into the Top 10. By the end of October, their cookie-cutter rendition peaked at No. 9, thereby matching the chart performance of the Beach Boys’ more difficult “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man).” Along the way, the Hondells appeared on the TV program Shindig, lip-synching “Little Honda” while straddling the mini-bikes. [Watch here.] But as it was originally a Beach Boys album track written by Brian Wilson and Mike Love, shouldn’t it have been the Beach Boys out there on TV, fake-singing their hit while humping (figuratively and literally) those little toys?

Maybe yes, maybe no. The answer varies in accordance with one’s opinion as to what the Beach Boys were about, and what they should have been doing in the late summer and fall of 1964.

Three years earlier, 16-year-old Dennis Wilson innocently suggested that the barely-formed Beach Boys (then calling themselves the “Pendletones”) could sing a song about surfing. Music publishers Hite & Dorinda Morgan recognized the marketability of the idea, and the Beach Boys were born. Still, nobody could have foreseen the extent of what was to occur; that somebody would think of blending Chuck Berry, the Four Freshmen and surf-lyrics; that by 1963 a national craze would be in full swing, with beach and surfing songs forming the basis of an entire (albeit very short-lived) sub-genre of pop music. The Beach Boys and Capitol Records had smartly capitalized on the opportunity, but the whole phenomenon was founded on an element of dumb luck.

It was only after the Beach Boys broke through and the money started pouring in that people would be motivated to reverse-engineer the band’s success, break it down to its component parts, and then try to replicate it. As Brian Wilson himself explained (or at least implied) in an interview in August 1964 (in the trade publication Music Business), the trick was to identify with “the young people” who comprised the teenage record-buying market. Brian specified two distinct ways through which a songwriter might do this: (1) identify with what teenagers do; and/or (2) identify with what teenagers think about. (He humbly left out the part about exceptional songwriting, production, and vocal talent.)

On the internal, thought-driven “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man),” Brian chose the latter strategy, and tried to connect with (what he hoped were) the inner thoughts of the audience. But up until that point, he and the Beach Boys had most often opted for the first method, on stuff like “Surfin’ Safari,” “Shut Down,” “Be True to Your School,” “Fun, Fun, Fun,” and most recently, “I Get Around”—songs that were based on the (presumed) lifestyle and physical activities of America’s teenaged Baby Boomers.

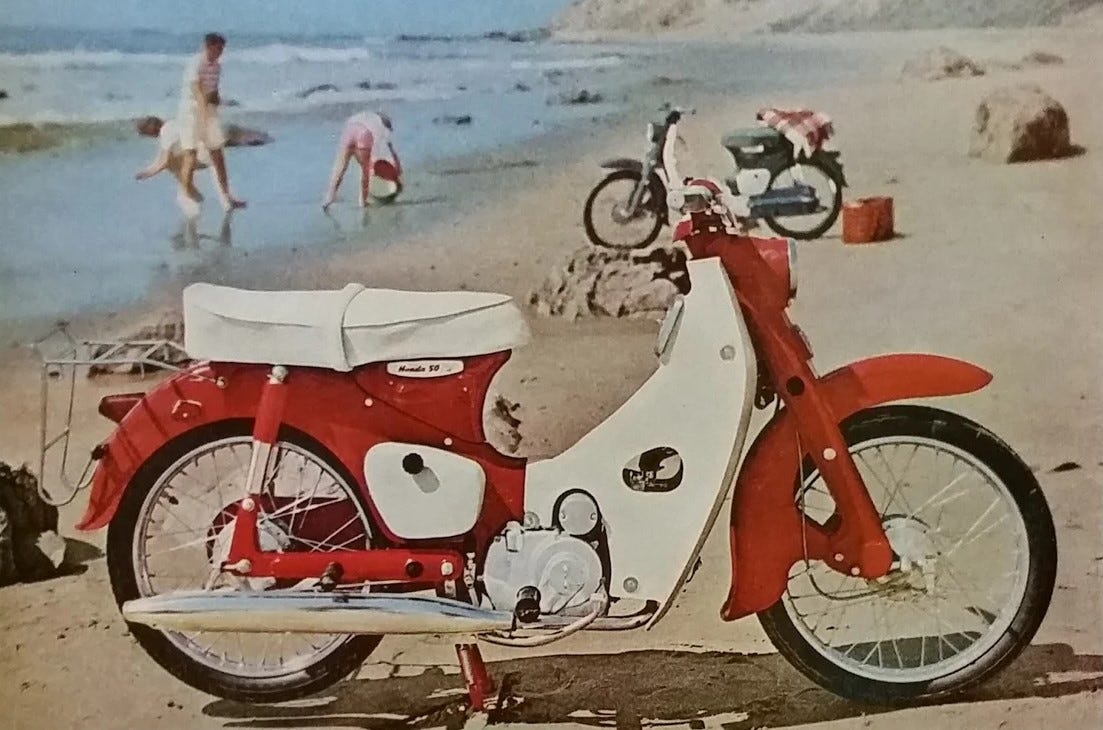

A song about having fun on one of Honda’s popular 50cc motorbikes was therefore consistent with the standard Beach Boy song concept, and as originally done by the Beach Boys, “Little Honda” was quite good. It succeeded entirely on the terms it set for itself. It’s hard to imagine a record that could better communicate the thrill of riding around on a Honda scooter. In fact, the recording itself was probably more exciting than the real thing. As a Honda sales pitch or radio commercial, it was outstanding—American Honda Motor Company, Inc. should have been delighted, especially if the Beach Boys weren’t paid for their promotion.1 However, for that very same reason, “Little Honda” was (and remains) sort of ridiculous if judged not as a commercial recording, but as a song, or piece of music outside the frame of commerce.

While Dennis Wilson’s original idea for the “song about surfing” had been honestly naive—Dennis himself was a surfer who had a genuine sense of what was happening at the South Bay beaches—“Little Honda” was more calculated. Without a doubt, it was conceived from the very beginning with an eye toward pumping, and then capitalizing on, a potential recreational craze. It was particularly crass too, marking the first time the Beach Boys went so far as to flag an actual consumer product—by name—in the song itself. It was as if “Little Deuce Coupe” had name-checked Ford, or if “409” specified that it was about a Chevy, while trying to make even the trip to the dealership sound like fun (as “Little Honda” does in the lyric about “going down to the Honda shop”). Or if “Catch a Wave” had specified a particular brand of surfboard that was best-suited for the new coastline craze.2 It’s possible that no Beach Boys song to date had been so purposefully formulaic.

Since the beginning, the Beach Boys had worn their commerciality on their sleeves, projecting an element of salesmanship in their songs—come on down and catch a wave, and you too can be sitting on top of the world! The band’s records succeeded not only as popular music, but also (even if people didn’t think of them like this) as advertisements for a semi-imaginary Southern California lifestyle. But that’s apparent mostly in hindsight. In the Beach Boys’ defense, they couldn’t have been too aware of what it was they were doing; that for whatever reason, they were good salesmen. Rather, they were just making the music they wanted to and getting on the charts the only way possible. Theirs had been an honest, uncynical commercialism. Still, at some point, somebody—perhaps a member of the Beach Boys group itself—was going to notice what they had been doing, and be concerned. And maybe try to do something about it.

But that person would have been a member of a very, very small minority. Few would have cared about the prospect of the Beach Boys becoming overly commercial—and therefore creatively insincere. As the Hondells would prove, in 1964 “Little Honda” was solid product. It was what American teenage music was supposed to sound like. (British teenage music was a separate matter; during the ‘64 “Invasion” it was sort of its own separate sub-genre.) It was a good song because the Hondells could get it to No. 9. It was a bad song insofar as it couldn’t reach No. 5 or No. 1. “Little Honda” fit comfortably within the Beach Boys’ established image, and nobody would have batted an eye if the Boys had kept it for themselves and released it as a single.

It’s not just that “Little Honda” could have been a Beach Boys single, but that it sounds like it was written expressly for that purpose. However, the group declined the chance to follow “I Get Around” with another dynamic record on the youthful theme of motorized fun & recreation. Instead, the Beach Boys put out the unique and inward-looking “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” (with “She Knows Me Too Well” on the B-side), while “Little Honda” migrated over to Brian’s friend and former songwriting partner Gary Usher, the producer who basically fabricated the Hondells, putting together a band whose very name was welded to the Honda brand.

In the end, the Beach Boys missed the opportunity to put out a single that would have outperformed the lesser version by the unknown Hondells—meaning also that the Beach Boys would have bested their own chart performance on “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man).”

Something was going on here. Considering that Brian maintained significant, if not total authority to choose the recordings the Beach Boys released as singles, it seems obvious—though not absolutely certain—what occurred. Brian might have understood how something like “Little Honda” was okay for the Hondells, an unknown group that was looking for a break (just as the Beach Boys had been in 1961-62). But in mid-1964, in the midst of the British Invasion and after the crowning achievement of “I Get Around,” the Beach Boys had to distance themselves from yet another fad—especially one that was still more childish and regressive (and frankly, feminine) than surfing or cars.3 It was better for the Beach Boys to move up and out, as indicated by both “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” and “She Knows Me Too Well.”

Yet Brian and Mike were the guys responsible for bringing “Little Honda” into existence in the first place. They wrote it. Moreover, they did good work—Brian took care in the production and arrangement while Mike’s lyrics are excellent for what they are. But they did this in service of a dumb, transparently commercial idea.4

Does the fact that Brian and Mike wrote the song automatically mean that they came up with the original concept? It seems possible that the idea didn’t originate with them, but somebody else. Maybe Gary Usher. This could explain why it was Usher and his Hondells who took “Little Honda” onto the hit parade.5

From a strictly short-term business perspective, the Beach Boys missed out on a good score when they let “Little Honda” go. Because the Hondells’ hit version was on the Mercury label, Capitol Records missed out too. Capitol was, at best, ambivalent about this turn of events. Somebody at the Tower really wanted to see the Beach Boys up on those little Hondas, for at some point a studio photo shoot was arranged in which the Boys posed astride the scooters in a manner similar to what the Hondells did on Shindig (or for that matter, what Capitol had done two years earlier, when the Beach Boys were photographed with a surfboard and “woodie” station wagon for the cover of Surfin’ Safari).

Soon after the Hondells entered the Billboard singles chart with their version on Mercury, Capitol tried playing catch-up, releasing “Little Honda” as the lead track on a quickly-assembled Beach Boys EP called Four by the Beach Boys, which Capitol marketed as a four-song, 45-rpm single.

Only then did the Beach Boys’ “Little Honda” appear on the Billboard chart. But it was too late. As of the time the Hondells hit No. 9, the Beach Boys’ original was languishing at No. 73. It would get no higher than No. 65. From Capitol’s perspective, a missed opportunity.

For whatever reason, as things played out, Brian and the Beach Boys remained at an arm’s length distance from “Little Honda”: album cut—yes; single—no.6 The Hondells’ unfortunate appearance on Shindig (and the Beach Boys’ silly Honda photo shoot) indicates what could have happened had the Beach Boys thrown in with the scooter-fad. Fortunately, they didn’t. With knowledge of the difficulties Brian would later experience in getting the public to take the Beach Boys more seriously, it would appear that the band dodged a bullet—one they themselves had fired off by writing and recording the song in the first place. However, doing that may have come at the cost of creating a little tension between Brian Wilson and Capitol Records.

Here in the fall of 1964 there is evidence that Brian and Capitol are not seeing eye-to-eye. “Little Honda” flattening at No. 65 was not good. Something like this had never happened with the Beach Boys. Although their forgettable second single, “Ten Little Indians,” had stiffed back in 1962 (peaking at No. 49), that was before the group had established its commercial reputation and fully-defined identity as a surf/teen/fad band, and in any case, failure could then be attributed to the poor quality of the song. In the case of “Little Honda,” the release of a surefire Beach Boys hit was, for whatever reason, just botched. It’s possible to see how, from Capitol’s perspective, the young man with the magic touch—the one who had just delivered “Fun, Fun, Fun” and “I Get Around”—picked the wrong song. What was up with Brian Wilson?

More ‘64 in Part 27 (not yet posted)

Back to previous entry, Part 25

Selected References for Part 26

Doe, Andrew. “Shows and Sessions 1961-2024.” Bellagio10452.com. At: www.bellagio10452.com/gigs.html

Grevatt, Ren. “The Beach Boys Ride the Trends.” Music Business, August 15, 1964.

Tiegel, Eliot. “4-in-1 Single to Be Bowed by Capitol.” Billboard, September 12, 1964.

It seems that Brian and Mike went so far as to ensure that the music and lyrics on the chorus accurately reflected Honda specifications: these bikes had three-speed transmissions, and the chorus duly runs through the gears—first, second, third—in succession, as the Honda goes “faster, faster.”

This shouldn’t mean that using the brand name of a scooter or motorbike in the lyrics or title of a song is inherently chintzy or undignified. See, for contrast, Richard Thompson’s 1991 folk-ballad, “1952 Vincent Black Lightning.”

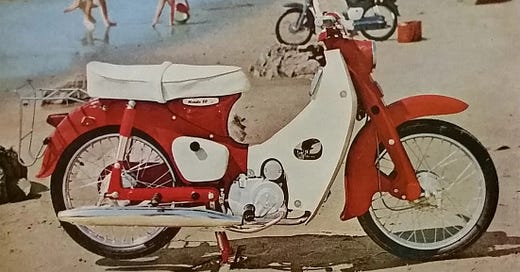

As seen in the photo at the top of this post, the Honda scooter featured a “step-through” body design—similar to the standard frame for (what were once called) “girls’ bicycles.” The step-through design is/was intended to accommodate riders who wear skirts. (Also, for what it’s worth, the Honda probably topped out at around 40-45 mph.) In England, the (Vespa) scooter had come to be associated with the cool “mod” scene; in Italy, a swaggering youth on a Vespa could be a chick-magnet. Not so in America; at least not in the mid-1960s.

If the absurdity of “Little Honda” doesn’t come through on the Beach Boys’ version, it’s because of the high level of musical and lyrical craftsmanship. The Hondells’ appearance on Shindig exposes the underlying problem with the song. By 1997, the year critics’ faves Yo La Tengo put out a heavily distorted, alterna-slacker version of “Little Honda,” none of this mattered.

The Beach Boys’ recording of “Little Honda” dated back to April, around the same time the band was filmed lip-synching their version for a teen movie then in production called The Girls on the Beach. The music soundtrack for the movie was credited to Gary Usher. It seems possible that Usher was the one who came up with the idea for “Little Honda,” basically commissioning the song (and also “Girls on the Beach”) from his friend Brian: can you give me a tune about Honda scooters? And then with Mike, Brian writes the song in a purely business frame-of-mind, and effectively gives it to Usher to produce for the Hondells or otherwise do with as he pleased. Still, even if that’s what occurred, Brian did take the time to record “Little Honda” with the Beach Boys (in a manner not unlike his production of “Don’t Hurt My Little Sister,” a song that wasn’t really intended for the Beach Boys). Why? Because the Beach Boys’ version was required for their appearance in the movie? Because Brian needed filler for the All Summer Long album? To provide Usher with a template to follow with the Hondells?

Because 1964 was a singles-driven era, it was possible for the Beach Boys to stay distanced from “Little Honda” while still including it on one of their albums. As of the time the Hondells put out their version of “Little Honda,” the Beach Boys’ original had already been released via the All Summer Long album. Still, enough people bought the Hondells’ record to get it to No. 9. It’s unlikely they would have bought the copycat single if they already owned the Beach Boys’ (better) version on All Summer Long. The inference is that the Hondells’ fans weren’t aware of the Beach Boys’ version because they didn’t own All Summer Long. In this genre of popular music, it was about singles, not albums. So Brian could, in effect, de-emphasize the Beach Boys’ version of “Little Honda” just by leaving it on All Summer Long as album filler.

Concerning "Little Honda" not being a BB single, the story goes that as Brian was mixing it, a complete stranger stuck their head into the studio and asked what it was. Brian said something like "our new single, what do you think of it?". The reported response was "don't like it" - and Brian canned it as a 45 on the spot.