In the middle of 1964, positive changes were in the offing for Brian Wilson. In April he took the landmark step of sacking his father Murry as formally-titled Beach Boys manager. Meanwhile, with “Fun, Fun, Fun” and especially “I Get Around,” Brian and the Beach Boys were proving they could stay competitive and innovate during the height of the Beatle-craziness. The group was unified as a band both on the road and in the studio. Brian was rapidly evolving as a producer, learning to synthesize Phil Spector’s methods with his own unique sensibility. Released in July, All Summer Long was the most well-produced Beach Boys album to date.

The latter portion of the previous chapter (Part 22) attempted to set the stage for the next offering from the Beach Boys: the “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” single in August 1964. In short, for somebody raised the way Brian had been, the process of “becoming a man” was no simple matter. Part 22 left off with the idea that the 21- or 22-year-old Brian would have been feeling the need to grow up, and that music would be the way for him to do it.

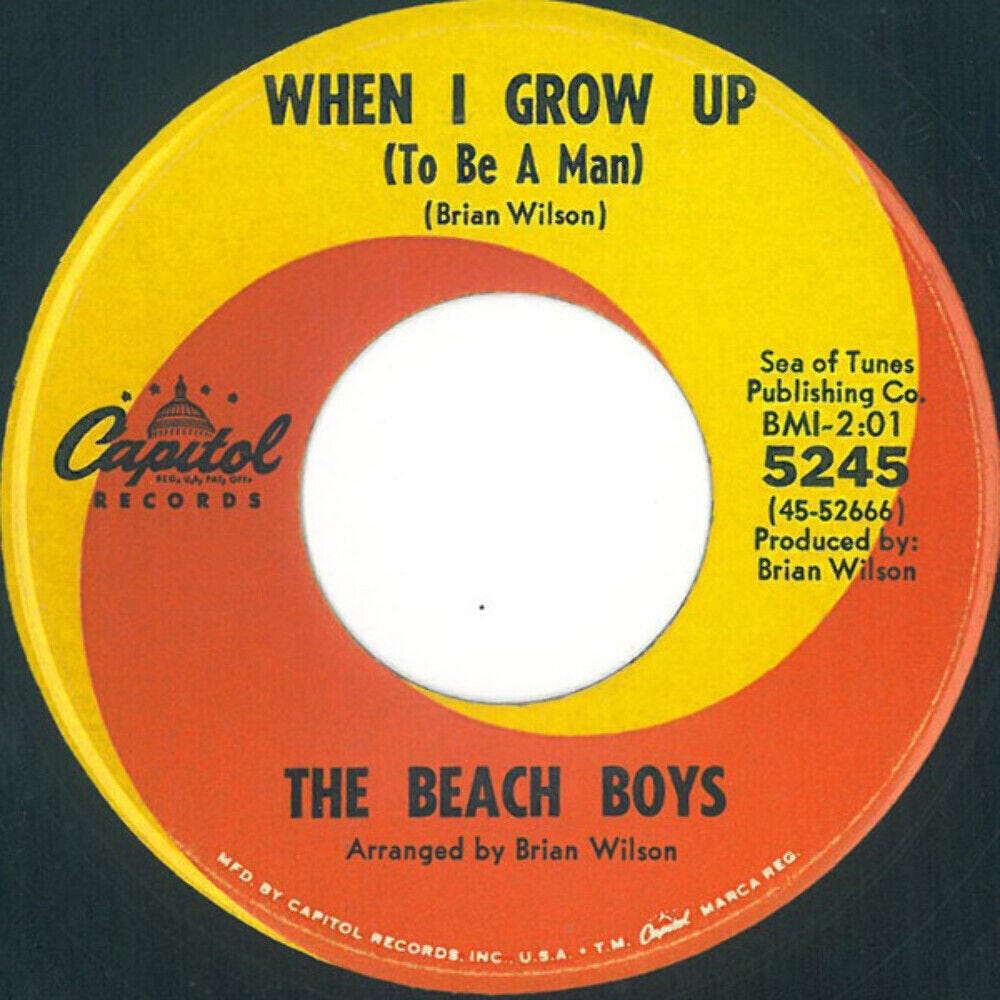

As of August 24, 1964 it had been about 3 months since the release of the Beach Boys’ most recent single, “I Get Around,” and only a month-and-a-half from its ascension to No. 1. The All Summer Long album—featuring about 10 new songs in addition to “I Get Around”—had appeared even more recently, in mid-July. Having given the group’s young fans more than enough time to take in all this new music, it was time for Capitol Records and the Beach Boys to put out the new late-summer A-side single, “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man).”1 On this tune Brian steered clear of high school imagery, teen scenes, custom rods, cruising, and summer fun. The song instead finds a teenage boy alone with his thoughts, asking himself specific, pointed questions about adulthood and the future, as time hurtles forward.

“When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” entered the charts in early September of 1964 and by the middle of October had gradually peaked at No. 9. Although a hit (or modest hit), the song never attained the standing of other well-known Beach Boys recordings of both earlier and later times. Arguably, it’s not well-suited for either fun, radio-friendly listening or live performance. It was musically and thematically complicated by the pop standards of the era. The song asked questions and gave no answers. While Mike Love sang the verses in what sounds like a purposeful attempt to sound accessibly “teenage,” his vocals don’t enter until after the song has already taken the listener unawares with the dissonant harmony tag/refrain.

In his 2017 book about the music of Brian Wilson, Christian Matijas-Mecca wrote that Brian arranged the harmony parts to “sit high in the band’s vocal register and it sounds somewhat strained, not unlike a male prepubescent voice that has not yet dropped but cannot easily find where it is supposed to sit.” Brian himself has disparaged the “whiney” quality of his own high-pitched vocal.

Meanwhile, throughout the song, a background vocal motif conveys the relentless passage of time, as the Beach Boys count off the years flying by, one after the other. Author Philip Lambert writes that the tune’s overall effect is to look “ominously and curiously into the future.” That sounds about right; the problem is that curiosity and ominousness make for a very disturbing combination, a pairing that forms the basis for suspenseful, grisly scenes in horror movies. “When I Grow Up” was not intended to horrify its young listeners, and of course didn’t, but with the passage of time, and with greater knowledge of Brian Wilson’s life story, a strain of anxiety and foreboding is undeniable.

This is all to say that “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” communicates the sense of a young life in transition, with the potential to achieve a state of being in the future, accompanied at the same time by a fear of not becoming something, or becoming something undesirable—all while the sands of time run out. At the time he wrote it, Brian seems to have convinced himself that such subject matter was commercial, claiming in the press that the song “certainly touches what every guy is thinking about.”

Maybe some guys think about the future like this, but certainly not every guy. Oddly enough, the depth of this two-minute number is most likely to be appreciated and understood not by young guys, but old(er) men who have learned that life does not in fact turn out as imagined; that years fly by mercilessly. An old man tells a youngster to spend the time he has wisely, because it will soon be gone, but the boy—the very person “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” was made for—doesn’t quite understand. He’s not able to grasp the power of time on that level. Yet Brian was sensitive to it at age 22, conceptualizing beyond his years. Maybe too far beyond. This is an old man’s song, written by a 22-year-old, intended for 15-year-old boys.

The subtlety of “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” is obscured by its frisky musical arrangement, its brevity, and the boyish vocals of the Beach Boys. Childlike the song may be, but not childish. It has a level of insight and intelligence that distinguishes it from similarly-themed songs—for example, the Four Seasons’ “Walk Like a Man,” which had fairly recently (in early 1963) established a precedent for teenage songs on the theme of being or becoming a man. Brian’s approach to the question was quite different, at least upon close examination.2 “Walk Like a Man” had focused on only one specific issue—what it means to behave like a man in the context of the young narrator’s current girl-problem. And the matter was resolved in two verses, as the father passes down the tenets of manhood to his son, who successfully applies them to a satisfying conclusion.

In contrast, “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” looked at manhood across the span of an entire life, while raising some pretty sophisticated questions: will I marry young? What kind of father will I be and what will my kids think of me? Will I have regrets later on? The song perceives that girls and women are not the same—that girls grow up too—and asks if the things that make girls attractive are the same as what will make a woman attractive. (Again: this is a song for middle-aged and old men to reflect upon.) And will the young singer be able to love his wife for the rest of his life?

The song answers none of these questions. It can’t answer them because they’re not answerable. And there’s also no father-character in the song to provide guidance. Neither Brian Wilson nor co-writer Mike Love were the type of son to seek dad’s counsel and dutifully follow his advice or direction, and it’s hard to imagine them injecting that element into a Beach Boys song. (The last time a father figured prominently was in “Fun, Fun, Fun,” where he comes off as a punitive buffoon.)

In 1964, nobody would have expected or wanted something like this from any popular teen-focused group. And even if, for the sake of argument, there was a place for such unsettled questions somewhere on the hit parade—as there was in the mid-1950s with Doris Day’s whimsical (and annoying) hit “Que Sera, Sera”—it’s not what anybody wanted from the Beach Boys, a group whose songs (ballads aside) leaned toward the extroverted physicality of surfing, car culture, and youthful sexuality.

It has never been said that anybody inside or outside the Beach Boys organization was bothered by “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” or otherwise gave Brian any grief about recording the song and then submitting it to Capitol as the new single. It came out, reached No. 9, and was more or less forgotten as everybody moved on.3 But even if nobody noticed it at the time, “When I Grow Up” signified a sharp left turn for Brian Wilson as songwriter and creative leader of the Beach Boys.

Still, “When I Grow Up” was not entirely unprecedented, necessarily. This wasn’t the first time the theme of a Beach Boys song diverged from commercial (audience) expectations. Back in the summer and fall of 1963—at which point the Beach Boys were widely celebrated as beach-surf-car band, and when that material was still fresh—they went sideways by putting out “In My Room” and “Be True to Your School.”

Appearing first as an album track on Surfer Girl, “In My Room” was a solitary, introspective ballad dealing with a teenager’s internal and unexpressed feelings, with not one nod to surfing, the beach, sunshine, car culture, or the outdoors. “Be True to Your School” might have been even stranger when it first appeared on the car-focused Little Deuce Coupe album in October 1963: seemingly from nowhere, amongst a collection of car songs (with a hot-rod on the cover), the surfing, drag-racing Beach Boys included this brassy production number evoking high school football games, cheerleaders, and lettermen jackets.

“In My Room” had been something of a happy accident. Writing the tune with Gary Usher back before the Beach Boys fully merged with the surfing fad, Brian did not really intend to do something so inward, expressive, and personally meaningful. The goal in these days, as Usher would later remember, was rather to write songs like Carole King and Gerry Goffin, whose “Up on the Roof,” as performed by the Drifters, first entered the charts at the end of 1962 and whose theme and lyrics could very well have inspired “In My Room.”

With “Be True to Your School,” Brian again turned away from tried-and-true Beach Boys themes, but with more awareness and conscious purpose than he had on “In My Room.” It’s unlikely he just stumbled into that extroverted “school spirit” concept and its massive studio production, and then decided to release it as an attention-seeking single in late October 1963 (with “In My Room” on the flip). It seems that Brian the teen-pop craftsman was then searching for new “fun” teen themes, and lit upon school spirit as something Beach Boys fans might be able to get behind.4 But he himself was unlikely to have cared about school pride any more than whitewall slick tires or “shooting the pier” at Huntington Beach. It was just something to make a record about.

And now, in the late summer of 1964, another unusual offering with “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man).” Like “Be True to Your School,” it was an A-side that unabashedly turned from typical Beach Boys subject matter, but this time the song hit closer to home, with Brian returning to the theme of solitary teenage introspection for the first time since “In My Room.”

All told, with “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man),” Brian was starting to stick his chin out as an artist. He was (1) writing from an internal perspective; (2) doing so with an increased level of awareness and purpose; and (3) leading with this material by putting it out as an A-side. He had never done anything quite like this before.

Keep reading about Brian Wilson and “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” here, in Part 24 of A History of Brian.

Selected References for Part 23

Benci, Jacopo. “Brian Wilson: Jacopo Benci Lets the Beach Boys’ Troubled Genius Have His Say.” Record Collector, January 1995.

Carlin, Peter Ames. Catch a Wave: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Beach Boys' Brian Wilson. Emmaus, PA: Rodale, 2006.

Felton, David. "The Healing of Brother Bri'." Rolling Stone, November 4, 1976.

Gaines, Steven. Heroes and Villains: The True Story of the Beach Boys. New York: Dutton/Signet, 1986.

Grevatt, Ren. “The Beach Boys Ride the Trends.” Music Business, August 15, 1964.

Lambert, Philip. Inside The Music of Brian Wilson: The Songs, Sounds and Influences of the Beach Boys' Founding Genius. New York: Continuum International, 2007.

Matijas-Mecca, Christian. The Words and Music of Brian Wilson. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2017.

Sharp, Ken. “Mike Love of the Beach Boys: One-On-One.” Rock Cellar, September 9, 2015. At: https://web.archive.org/web/20180612170213/https://www.rockcellarmagazine.com/2015/09/09/mike-love-of-the-beach-boys-one-on-one-the-interview-part-1/2/ (last accessed May 24, 2024)

This might be a good point at which to remember the rapid rate of commerce in pop music during the early and mid-1960s. Groups like the Beach Boys and the Beatles were expected to put out three albums per year, and new singles every three months or so. There were probably many reasons for this mode of business, one of which being that none of the music was taken very seriously. (The serious part, as always, was the money the songs generated.) At the same time, the incessant churn of commerce may have given some of the more talented music makers—those who were young and exceptionally creative, like the Beatles and Brian Wilson—the impetus to evolve and innovate as songwriters and record-makers. It’s possible that for a truly creative person, it’s easier (at least for a while) to keep up with the demands of commerce by coming up with fresh ideas. Today, an interval of say, one year, (roughly the time between “Little Deuce Coupe” in 1963 and “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” in 1964) is nothing, but back then, it was enough time for capable musicians to take great strides in terms of theme, sound, and presentation. As mentioned in Part 15 of this series, the transition from 1963 to the era of “I Get Around” and “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” in 1964 was dynamic, as it is commonly understood to mark the phase during which “Fifties” culture (and music) ended, and the “Sixties” began. (1964 was not only the year of “I Get Around” and the Beatles’ British Invasion hits, but also The Kinks’ “You Really Got Me” (August). Though Bob Dylan wouldn’t record the definitive version of “Mr. Tambourine Man” until 1965, he wrote it and frequently performed it live in 1964.)

In 1994, Mike Love successfully brought a lawsuit to retroactively secure a writing credit on “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” and other Beach Boys songs. While “When I Grow Up” obviously bears all the hallmarks of the classic, introspective “Brian Wilson song,” it can be assumed that Mike duly contributed to the lyrics—most likely in the verses where he takes the lead vocal. But Mike’s motivation as a songwriter probably differed from Brian’s. In 2015, journalist Ken Sharp asked Mike about the song, noting specifically how mature and forward-thinking it would have been for a writer in his early twenties. “What prompted that kind of thinking?” Sharp asked. Mike then expounded on astrology (the difference between his and Brian’s astrological signs), and how he wanted to mitigate the “desperation” and “melancholy” in Brian’s songs. This indicates that Brian was the one interested in the subject matter of “When I Grow Up”—growing up, uncertainty, becoming man, asking questions, the passage of time—while Mike was motivated to make the song more “positive,” without giving much thought to what it was actually about. This doesn’t mean Mike is undeserving of credit for his contribution. In the end, and for different reasons, neither of the credited songwriters of “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” have been willing or able to comment on the song with much clarity or insight. This is typical for the Beach Boys.

One reason “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” fell through the cracks is its absence from the Beach Boys’ Endless Summer, the smash hit compilation album from 1974. For the normal person with finite resources who was unable or unwilling to buy several Beach Boys albums, Endless Summer (as compilation albums tend to do) conveniently dictated which songs were worthiest. In addition to well-known hits like “Surfin’ U.S.A.,” “California Girls,” “Little Deuce Coupe,” and “I Get Around,” Endless Summer brought lesser-known album tracks and B-sides into wider public awareness—songs like “The Warmth of the Sun,” “Wendy,” “Catch a Wave,” “Let Him Run Wild,” and “Girl Don’t Tell Me.” Had “When I Grow Up” been included in the set, it would have been less likely to become a curio in the group’s ‘60s singles discography, known only to serious Beach Boys fans.

The weirdness of “Be True to Your School” and Brian’s possible motivation for doing it was addressed in Part 15 (“The Birth Pangs of an Artist”). It’s only speculative though; Brian has scarcely commented on “Be True to Your School” beyond saying that doing the song was a big mistake. In contrast, Mike Love—who takes credit for the lyrics but not the music, original subject matter, or title—takes pride in the song, stating, “I took great care in every word.”