In April 1964 the Beach Boys fired Murry Wilson as band manager. In May, “I Get Around” came out as a single, ascending the national chart throughout June and reaching No. 1 by July 4. With “I Get Around” as the anchor, the Beach Boys’ album All Summer Long was released in mid-July, in the midst of the band’s summer tour.

It is commonly said that Carl Wilson was the “peacemaker” in his family—a thankless (and impossible) job he may have intentionally taken on as a personal responsibility or one that he just assumed naturally, as a matter of his personality. Among the Beach Boys, Carl was the member who was most able to empathize with Murry’s plight. And so (as mentioned at the end of the previous post) it was Carl who helped Murry connect with a new upstart rock ‘n’ roll band to manage. That band was then calling itself “The Renegades.”

The following chapter in A History of Brian Wilson looks at what transpired once the Renegades partnered with Murry Wilson.

The Renegades were a pretty decent band. Though perhaps untutored in the finer aspects of the music business, they had been knocking around for a while, had done some recording, and were well-practiced. They were good enough in any case to impress Murry Wilson, and more importantly, Carl Wilson—Carl wouldn’t have set them up with his father if he thought they were no good. Carl was the “rock ‘n’ roller” in the Beach Boys—the youngest member, the guitar player, the one who really dug Chuck Berry, and now, the Beatles. (In 1964, Brian admired and respected the Beatles, but Carl was an outright fan.) Carl was likely to have been receptive to the Renegades’ rock ‘n’ roll stance—they probably leaned more toward instrumental chops than vocals, and their R&B-influenced sound was somewhat rare for a white (i.e., non-Chicano) Los Angeles youth band of this period. (They had covered Willie Dixon and had a noticeable Ray Charles influence on a song or two.) Arguably, the Renegades were reasonably well-positioned to make some noise in the new post-Beatles scene, at a time when papa-doo-run-de-run-day was being replaced with yeah-yeah-yeah.

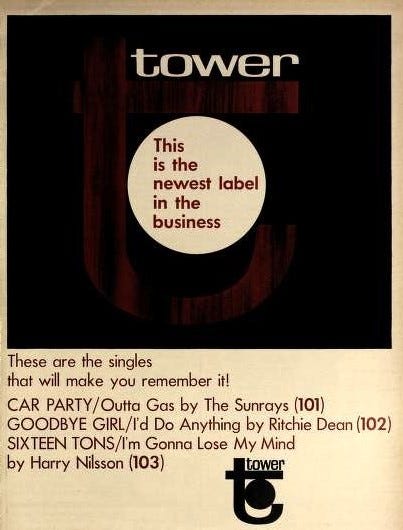

Having been sacked by the Beach Boys in April of ‘64, Murry was probably working with the Renegades no later than summer, shaping their musical sound and negotiating a recording deal. Murry’s contacts were of course with Capitol Records, which always had to exercise caution in its dealings with the man who was strategically positioned as the overbearing father of cash-cow Brian Wilson. Capitol would of course agree to release the Renegades’ music—but only on its newly-formed “Tower” imprint, a down-market subsidiary.1

The Renegades’ debut single came out in September. By then, under the guidance of Murry and the label, the somewhat rough, R&B-tinged band had become “The Sunrays,” a lineup that would soon mutate fully into a five-man vocal harmony group wearing Kingston Trio-style striped shirts while singing about sunshine and cars. In his book The Nearest Faraway Place, Timothy White observed that the name “Sunrays” is basically an anagram of “Murry Wilson.” (Mur-ray Wil-sun.)2

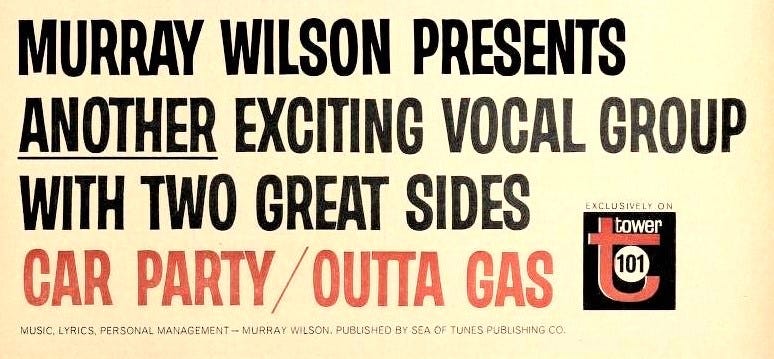

What Murry had not been able to accomplish with the Beach Boys he would now do with the Sunrays: use the band as a vehicle to further his own songwriting career. The new Sunrays single boasted Murry Wilson compositions on both sides. Promotional ad-copy in the trades (e.g., Billboard) stated that Murry was not only manager of the Sunrays, but also provider of music and lyrics.

If that isn’t enough to clarify Murry’s state of mind with respect to Brian and the Beach Boys, there is the substantive content of Murry’s songs themselves. Anyone doubting that Brian Wilson’s success threatened and offended his father should listen to Murry’s “Outta Gas” and “Car Party,” as recorded by the Sunrays in 1964. When heard in their proper historical context, these obscure recordings defy belief.

It comes as no great shock to find that neither “Outta Gas” nor “Car Party” are very good. “Outta Gas” is flat and musically unremarkable; whatever garage-band chops the Sunrays had are awkwardly shoehorned into Murry’s faux-Beach Boys pastiche. “Car Party” (the A-side) is a bit more interesting; the dynamism and creativity of “I Get Around” may have inspired Murry to push himself. Just as Brian did on “I Get Around,” here Murry experimented with musical “texture”—the time signature shifts from 2/4 in the verses (bringing to mind Gilbert & Sullivan’s “Three Little Maids”) to 4/4 in the chorus. Murry answers Carl’s “I Get Around” guitar solo by having one of the Sunrays play a matching eight-bar break, which is followed (at about 1:00) by a two-bar transition lifted from the intro of Elvis Presley’s “Jailhouse Rock.” The song then returns to the square-dance feel of the verse.

Certainly, it’s the lyrics of both “Outta Gas” and “Car Party” that are most important. Back at the tail end of 1963, the new Wilson-Love tune “Fun, Fun, Fun” had stirred things up with its playful element of defiance. This was probably what motivated (at least in part) Murry to obstruct its creation by canceling its first recording session (as mentioned previously in Part 16). A few months later, “I Get Around” communicated something about adulthood, independence, success, and the prerogatives of youth—particularly during the chorus on which Brian soared, singing about mobility, steadiness, and “good bread.” It was that very bread—Brian’s money—that was the focus of “Outta Gas.”

As suggested previously (in Part 18, “The Firing of Murry Wilson”), Brian was by now making good bread not only for himself, but the entire Wilson clan. He had supplanted Murry as provider and had therefore implicitly challenged the power Murry had always held in the family. Murry was in denial of that humiliating reality, telling himself (and probably anybody that would listen) that he was responsible for the Beach Boys’ success.3

If that was true, it meant Murry was not receiving handouts from his son but had instead duly earned his newly-acquired song-publishing wealth. It meant Brian and the Beach Boys had been insufficiently grateful for the gifts Murry had selflessly bestowed upon them. And it meant Brian and the Boys had benefited from a windfall that rightly belonged to Murry. All around, it was a great injustice. Accordingly, “Outta Gas” was focused on the issue of money, reflecting Murry’s wish that Brian didn’t have so much of it, and/or Murry’s belief that Brian hadn’t worked hard enough or otherwise deserved his wealth.

Therefore, the teen narrator of “Outta Gas” does not make good bread, nor does he get around. He’s sort of a loser—off the scene with no money and no car, striking out with the girls at school:

Outta gas (outta gas)

ain’t so funny

outta gas (outta gas)

havin’ no money

outta gas (outta gas)

ain’t so cool

it’s a drag losing out with the girls at school (wah-ooo)

As the song ends, the poor guy has taken on menial jobs (“serving pizza and washing trays”) and is working hard to make money, but it’s clear he still hasn’t made it.

Murry didn’t write this as a gag. It wasn’t one of those comedy songs in which the very premise is a joke. (Like for instance, the Beach Boys’ “No-Go Showboat,” a song about a custom-rod that was all flash and no engine; so slow it loses a street race to an ice cream truck.) Murry intended “Outta Gas” to be fun listening, but the underlying message was sincere. The song effectively told Brian he was a loser—or at least that Murry would have preferred to see him mowing the lawn in Hawthorne or sweeping the floor at a pizza parlor.4

When “Car Party” begins, the kid-narrator is “having some fun” cruising with his friends (in a deuce coupe, it seems) and “nothing is wrong.” Then the cops pull them over and the fun stops. In the second chorus Murry’s oafish lyrics reiterate the element of “Fun, Fun, Fun” he approved of, as the singer comes to realize:

Car party / isn’t so cool now

car party / I’ve been a fool now

car party / like the Beach Boys say

yes my dad’ll take my keys away!

The morality tale reaches its climax as the kid is humiliated before a court of law while the Sunrays sing, “I gotta call my dad so he’ll pay the fine” several times over the fade-out.

The message of “Car Party” differed from “Outta Gas.” “Car Party” was less about money than Murry’s opposition to Brian’s personal freedom and independence. Once the boys in the song start “cruisin’ the town,” they’re quickly “flagged down” by the “red light” of the police car, leading ultimately to the courtroom denouement and the singer’s acknowledgement that he needs his dad’s help.

This was an authoritarian pop song whose prime concern wasn’t money but control for its own sake. Heard in this light, Murry’s musical quotation of “Jailhouse Rock”—which ushers in the punitive part of the song and the courtroom sequence—seems rather sinister. (And perversely clever, even if Murry did it inadvertently.)

In his 2016 book I Am Brian Wilson, Brian looked back and observed that his cruising songs “were about getting in the car with your buddies and driving around with the top down and getting burgers and looking at girls.” This was true for the normal teenage listener, but for Brian and Murry, “Fun, Fun, Fun” and “I Get Around” were freighted with deeper, symbolic meaning. Those two Beach Boys hits, together with Murry’s “Outta Gas” and “Car Party,” constitute a secret dialogue on 45-rpm vinyl, in which father and son send coded messages to each other. Brian’s message was I’m leaving and I’m going to be free. Murry’s response: No—you’re not going to “get around.” You’re “outta gas” and you’re not going anywhere—not without me.

In the end, we are left with an unanswerable question: did Brian and Murry have any awareness that they were communicating with each other in this manner, or was it unconscious?

I really think Murry wanted to talk to his kids through the radio while they toured the country.

—Rick Henn, Sunrays

Brian Wilson biographer David Leaf has observed that once the Sunrays started releasing singles, Murry and Brian were in direct competition. This is true, but Murry had always competed with Brian. The difference was that it was now occurring openly, in the public arena of the record business.

While it is doubtful that Brian ever took Murry or the Sunrays to be genuine musical competition, the situation was awful for him because his own father was out to prove that he was nothing. Brian was now too big to be forced to defecate on a newspaper, but if the Sunrays—dressed the same as the Beach Boys, singing about the same things in the same musical style—could overtake the Beach Boys on the charts for even one week, Brian’s humiliation would have been sufficient. Those were the stakes. As always, the one-way competition between Murry and Brian was not so much about music as basic human dignity.

Meanwhile, the Sunrays took a shine to Murry. They would literally sing his praises the following year with a song they wrote and recorded especially for him called “Our Leader.” Harmonizing in Beach Boy-style, on this track the Sunrays prostrated themselves before Murry, honoring him as “a very great man.” (This was recorded as a private token of gratitude and not originally intended to be heard by the public.)

The Sunrays were young and naïve. They had no way of knowing the underlying depravity of Wilson family politics or the unfortunate role they were now playing. Still, they were everything Murry wanted Brian and the Beach Boys to be: humble, pliant, willing to sing Murry’s songs (and unsuitable cover tunes of Murry’s choosing), and so honored by the opportunity to bask in Murry’s radiance that they are moved to write songs in praise. This is what had been expected from Brian—to use his talent not only to make his parents rich, but genuflect while doing so.

Brian had indeed made some concessions, but he had so far refused to hand over his music. He kept his balls, and instead created some durable rock and pop. And the Sunrays never made it, of course. In later years some of them would make public statements in defense of their “leader,” whose reputation they believed to have been impugned by false or overblown stories of child abuse.

The 2015 motion picture Love & Mercy portrays Murry’s Sunrays gambit as a hurtful betrayal of Brian, and indeed it was. Which is to say, it was business as usual for Brian, consistent with the only life he had ever known. Yet there was a potential upside. If it is assumed that Murry would not have remained bedridden forever after being fired, and that he would rise again to pursue and harass Brian, it was better that his challenge came externally than from within. The more distanced Murry was from the Beach Boys’ spiritual and creative center, the less damage he could inflict; the less likely he would be falsely praised as a stalwart protector and supporter of the Beach Boys; the less likely it was he could seize credit for the group’s musical quality or success.

In short, it was better that Murry destroy the Sunrays’ career (for instance, by directing them to record garbage like “Car Party”) than that of the Beach Boys.

Seen in this light, it would appear that Carl Wilson’s intra-familial diplomacy smoothed things out for the Beach Boys in 1964. Murry had been marginalized (though not fully put out of commission) and his corrosive effect on Brian could now perhaps dissipate. Hopefully Murry would channel his destructive energy toward the hapless Sunrays while the Beach Boys could forge ahead with more breathing room, as a unified, five-man group that could exercise greater autonomy over itself.5

The Beach Boys now had about two years of professional experience under their belts. Collectively, the group could write, produce, and perform its own material, and, as now demonstrated by “I Get Around,” reach the very top of the national singles chart with a record that had nothing to do with the beach. Everything pointed to the possibility that the Beach Boys could not only survive, but improve and evolve—and do so with reduced meddling from both the label and Murry Wilson.

Of equal if not greater importance were the implications for Brian Wilson as an individual. He would never really be able to liberate himself from either the past or the crippling situation that had long been forming, which would eventually solidify and encircle him. Awful as it is to recognize, Brian would indeed be “outta gas”—defeated, in a sense—by the end of the decade, as the intractable realities of his life subsumed him and short-circuited his career.

As of the middle of 1964, however, Brian had successfully stiff-armed his father, creating some much-needed space between himself and the noisiest, most readily identifiable source of negativity, suppression, and illness in his life. To better appreciate what this portended for Brian, the Beach Boys’ music of 1964 should be explored in further detail.

A closer look at the musical and personal changes of 1964 starts in the next chapter, Part 22 of A History of Brian Wilson

Back to Part 20 of A History of Brian Wilson

Selected References for Part 21

Brian Wilson: A Beach Boy's Tale. Directed by Morgan Neville. Peter Jones Productions, 1999.

Bündler, David. “The Pageant of Richard Henn.” 21st Century Music, Vol. 7, No. 2, February 2000.

Carlin, Peter Ames. Catch a Wave: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Beach Boys' Brian Wilson. Emmaus, PA: Rodale, 2006.

Crowley, Kent. Long Promised Road: Carl Wilson, Soul of the Beach Boys. London: Jawbone Press, 2015.

Ear Candy Mag. “Interview with Eddy Medora (10-28-03).” At: https://www.earcandymag.com/sunrays.htm

Gaines, Steven. Heroes and Villains: The True Story of the Beach Boys. New York: Dutton/Signet, 1986.

Leaf, David. The Beach Boys and the California Myth. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1978.

Murphy, James B. Becoming the Beach Boys 1961-1963. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2015.

Stebbins, Jon. The Beach Boys FAQ: All That’s Left to Know About America’s Band. Milwaukee: Backbeat Books, 2011.

White, Timothy. The Nearest Faraway Place: Brian Wilson, the Beach Boys and the Southern California Experience. New York: Henry Holt, 1994.

Wilson, Brian, with Ben Greenman. I Am Brian Wilson. Boston: Da Capo Press, 2016.

Wilson, Murry. Letter to Brian Wilson. May 8, 1965. Collection of Hard Rock International/Hard Rock Memorabilia.

It is possible that Capitol created the Tower label for the express purpose of putting out Sunrays singles. In his book Long Promised Road: Carl Wilson, Soul of the Beach Boys (Jawbone Press, 2015), Kent Crowley wrote that the idea behind Tower was to avoid any confusion that might result from having two similar groups—the Beach Boys and the Sunrays—on the same label. If this is true, it suggests that in the end, Capitol wouldn’t have formed Tower but for Murry Wilson’s effort to compete with the Beach Boys. On the other hand, Harry Nilsson claimed to be the first artist signed to Tower. See Alyn Shipton, Nilsson: The Life of a Singer-Songwriter (Oxford University Press, 2013). If that’s true, then it might cast some doubt on the idea that Tower was formed for the express purpose of putting out Murry’s tunes with the Sunrays.

At this point, it’s worth taking a moment to recall the origins of the Beach Boys back in 1960-61, when (in various formations) they auditioned for Hite & Dorinda Morgan of Guild Music. The Morgans recognized the boys’ raw talent, but initially passed because they presented themselves as imitators—of the Kingston Trio and probably the Four Freshmen too. But the Morgans didn’t reject the future Beach Boys outright; they (apparently) only encouraged them to do something new with their abilities. Which the group of course did—and all without the assistance or guidance of Murry Wilson. (For more on this, see the four-part supplement “The Founding of the Beach Boys.”) In the case of the Renegades/Sunrays, Murry did the opposite—he suppressed the band’s natural musical inclinations and shaped them as rank imitators of the Beach Boys, right down to their striped-shirt attire. (The reason the Beach Boys had worn the stripes in the first place was because it was Murry’s idea to imitate the look of the Kingston Trio.)

Again, as previously suggested in Part 18, it was humiliating only because Murry—an egregiously abusive father—was the type of man who would be humiliated by his son’s success. A different kind of father wouldn’t necessarily have been “humiliated” at all by this turn of events.

Murry could (and maybe would) have justified “Outta Gas” by pointing to Eddie Cochran’s hard-luck tale “Summertime Blues” (covered by the Beach Boys in 1962), which established a precedent for songs in which a teenager is busted, frustrated, and thwarted by adult authority.

This is not at all to imply that Carl matched his father with the Renegades/Sunrays as a Machiavellian diversionary scheme. It’s very unlikely Carl intended the Renegades to serve as Murry’s chew-toy, or that Carl expected Murry to mismanage them. Things may have turned out that way, but it’s more probable that at age 17, Carl just wanted to improve his dad’s situation, believing that Murry’s management of his pals in the Renegades would (or could) be win-win-win: for Murry, the Renegades, and the Beach Boys.