The previous chapter dealt with the Beach Boys’ mastery of an intentionally “teenage” and fad-oriented model of record-making. This mode of business differed from what was to occur within a couple of years, by which time a new kind of artistry was finding its way into the youth-driven commercial pop scene.

What qualifies as “art?” As of 1962 and 1963 (their heyday as purveyors of good surf and car songs) were the Beach Boys “artists?” Was Brian Wilson born an artist, or did he only become one later in life? If the latter, how and when did it happen?

Though Brian was talented, clever, and creative, the primary impetus for his earlier songs was most often commercial rather than self-expressive. He made good records about things that meant absolutely nothing to him: Brian didn’t surf, didn’t like the beach, and didn’t customize hot cars in his spare time. If he didn’t already know it when the Beach Boys first stumbled into success with “Surfin’,” Brian would soon learn that pop records, regardless of quality, were conceived and crafted to meet preexisting consumer preference. And that was okay—whatever artistic ambitions Brian had in the early days were adequately satisfied by the record-making process itself.

The next several installments of A History of Brian Wilson examine Brian’s transition from record-maker to artist in the mid-1960s.1

In 2002, a journalist asked a 60-year-old Brian Wilson if he would have become a musician without his “dysfunctional” family background. Brian’s reply was semi-contradictory. “Probably not,” he said, and then followed up with, “but I was definitely born to sing, to be an artist.”

Picasso said that “if a work of art cannot always live in the present, it must not be considered at all.” An exacting standard, but if true, the artist creates something of lasting worth; something that will outlive him and successfully communicate with people in the future. Insofar as Brian had artistic impulses in 1963, he would have been facing a quandary. He would have been feeling the need to create durable work while nevertheless wanting to remain a hitmaker. He would have to figure out a way to reconcile these two goals. The performer who’s in it just for the dough doesn’t have to deal with this challenge, nor does the maniacal purist toiling anonymously in the basement. On the Little Deuce Coupe album in fall 1963, Brian’s musical ideas and the Beach Boys’ fine harmonies were put to service in celebration of “Naugahyde bucket seats.” In the future, that wasn’t going to cut it.

The tension was embedded in the grooves of the Beach Boys’ main 45-rpm single of the time frame between fall and Christmas 1963. The A-side was “Be True to Your School,” the only non-vehicular song on the Little Deuce Coupe album. It was a big, orchestral production that sought to convey energetic high school spirit while lecturing listeners in the value of loyalty to one’s school (or at least to the school’s football team). Though not wholly inconceivable that Brian really felt this way about high school, “Be True to Your School” comes off as one of the most insincere and pandering pieces of music ever to bear his name.

This song seems to have just come out of nowhere, in the midst of the Boys’ surf-and-car era, which had been purring along nicely. What was going on?

It could be that in middle of 1963, following “Surfin’ Safari,” the inauguration of the surf-craze with “Surfin’ U.S.A.,” the release of the surf-heavy Surfer Girl album, and the writing and recording of the car songs with Roger Christian, Brian was searching for non-beach and non-car song ideas. The implied question: is there anything else we can sing about?

If Brian was motivated to move beyond surfing and cars, his instincts were sound. However, there was a catch: any new song concepts had to be purposefully tailored for the Beach Boys’ teen and pre-teen fans. Brian would have been aware of this reality.

An imaginary internal dialogue:

Q: What’s going on in the lives of teenagers that would work for a Beach Boys single in 1963?

A: Surfing! Kids are really into surfing right now, and they want to be surfers.

Q: No. Something besides that. We can’t do beaches and surfing forever.

A: Are you sure about that?

Q: Look—

A: The kids are into cars. Hot rods, racing.

(pause)

At least the boys are into that stuff.

Q: No, not that either. We just wrote and recorded a bunch of songs about cars—hot cars, fast cars, slow cars, “cherry” cars, girls who like cars, car clubs, custom-rods, drag racing, even a car crash ballad—and we’re gonna put those out soon. I mean besides surfing, pretending to be a surfer, or fixing up a cool car. Something kids can relate to.

A: Well, kids go to school, don’t they? Do a song about school.

Q: But going to school isn’t fun. The Beach Boys are supposed to make happy, fun music.

(pause)

At least on their A-sides.

A: “Surfer Girl” was the last A-side. That was a ballad. Was it “fun?” Was it “happy?”

Q: It had the “surf” thing going for it. Even though it wasn’t really about surfing, we could get away with it because it had surf imagery. Also, it’s great.

A: Then do another ballad. Just make sure it’s as good as “Surfer Girl.”

Q: We could put out a ballad last time because we were coming off “Surfin’ U.S.A.”/”Shut Down.” We were hot. We had leverage. And by the way, “Surfer Girl” was buttressed by a very strong B-side. But we can’t do two emotional ballads in a row. This is a business, you know.

A: Not even a car ballad?

Q: We already did one. Literally—“Ballad of Ole Betsy.” And it’s not hit single material. Good tune, nice, a bit corny and old-fashioned.

A: Then write a car ballad that is good enough. Challenge yourself! Is it possible to write a song about cars or drag racing that is nevertheless honest, sensitive, and meaningful?

Q: Yes, and that would be “Don’t Worry Baby,” but I’m not aware of that yet. This is still the middle of 1963.

A: I’m telling you, look to school for song ideas. Chuck Berry made school sound fun—just listen to “School Days.” It can be done, you know.

Q: Hmm. You’re right.

(pause)

Uh, I think I’ll go back and listen to “School Days” more carefully to see if Chuck was really saying school was fun, or whether the fun started after—

A: Forget that! It’s a good idea to put out a single that’s not about beaches or cars, but we’re on a tight deadline. The Beach Boys can do this! All we have to do is figure out a way to emphasize the fun parts of school—the part of the school experience that the kids like.

Q: And what part would that be?

Of course, it’s impossible to know Brian’s actual thought process, but the decision to make “Be True to Your School” had at least something to do with these sorts of concerns.2 With Mike Love’s lyrics clarifying the general concept, “Be True to Your School” went all the way to No. 6 on the singles chart—higher than any Beach Boys single to date except “Surfin’ U.S.A.”—suggesting that the song did not conflict with American youth culture as it existed in fall ‘63, and that Brian’s commercial instincts were sound. There’s also the possibility that with the previous A- and B-sides being “Surfin’ U.S.A.,” “Shut Down,” “Surfer Girl” and “Little Deuce Coupe,” the Beach Boys had accrued a level of credibility and trust from their fans, who bought “Be True to Your School” out of habit or reflex, resulting in an inflated chart performance.

Regardless of its success and the reasons for it, “Be True to Your School” had an expiration date shorter than any surfing or car song the Beach Boys ever recorded. It’s just a bad song; one of the most backward hits ever recorded by a great rock ‘n’ roll group. While the Beach Boys subsequently recorded many great songs (hits and non-hits alike) as well as some clunkers, “Be True to Your School” lingers as an example of the group’s retrograde tendencies and a subtle indicator of the punitive authoritarianism that was baked into the group and constrained its creativity.

As such, the song eventually earned its place alongside the various other millstones round Brian Wilson’s neck. When asked about it approximately 10 years after its release, an effectively-retired Brian said he wished people would ignore the words and just listen to the music. Although later versions of the Beach Boys would become more purposefully associated with conformity and authoritarianism, from Brian’s perspective as a creator, “Be True to Your School” was a self-gifted Trojan Horse through which the group symbolically, and in Brian’s own words, “blew their career” back in the fall of 1963. In short, Brian would come to recognize that he had made a mistake.

If listeners flipped the single over, they would hear “In My Room,” a song that dated back to the partnership with Gary Usher and the days when Brian was still writing songs in his parents’ house. Murry and Audree had previously converted the Wilson garage into a music room, and that is where Brian studied, played, and eventually began to write music. At some point during his teen years Brian moved out of the cramped bedroom he shared with his brothers and started sleeping in the music room too.

Later, during one of the writing sessions in which Brian and Usher batted ideas around, the topic turned to the very room in which they were writing, and Brian’s relationship to it. Their discussion eventually resulted in “In My Room.” At the most literal, outermost level, the song is about a teenager’s bedroom. Underneath, it’s about the actual music room in the Wilson home. At its truest core, however, the “room” is a metaphor, as the song deals with the process through which Brian used music to safely express himself without fear of assault and persecution by his father. Beach Boys fans certainly didn’t know this at the time, nor did Brian even; it was only later that he came to understand he had written about the reality of his own life.

It therefore seems that at age 20 in late 1962 (which was around the time “In My Room” was written), the creative process had liberated Brian’s unconscious to tell him things about himself that he wasn’t fully aware of at the time. It appears that Gary Usher could be a sympathetic and non-judgmental collaborator, willing to write words that acknowledge not just tears, but isolation, worry and fear. Conceptually, the song was well off the beaten path for 1962 or ‘63.

“In My Room” boasts one of the great group vocals from the Beach Boys. Still, because it says so much about Brian, it belongs on the short list of his signature songs. At the same time, it remains as accessible as any of the other teenage songs that the Beach Boys were doing in these days. Any young person should be able to relate to “In My Room.” Its placement on the flipside of “Be True to Your School” helps explain why. The same youth who spends his days penned with the herd in the Pavlovian environment of high school might value a little time alone to actually feel like a living person. As would a kid like Brian, one who is struggling with an impossible situation at home.

The “Be True to Your School”/”In My Room” single presented two sides of the teen (and adult, for that matter) experience: on the A-side there was falseness and doing what they tell you to do with a smile on your face. On the flip, there was realness. The distinction was also between group identification and individual self-awareness—that is, individual self-respect.

This one single, with its A- and B-side, illustrates how as of late 1963, Brian was already approaching a vaguely-defined crossroads. In one direction there were songs purposefully conceptualized for the teen and pre-teen market, which included surfing and hot-rod/street-rod songs, and now perhaps, the high school song. In the opposite direction was unspoiled territory where Brian could choose to write music that came directly from his heart and life experience, with no regard for sales. Somewhere in the middle was a narrow path along which he (and by extension, the Beach Boys) could make relatable, commercial music that still meant something to him as a person.

“In My Room” was that kind of song, and so was “Surfer Girl,” a romantic love ballad that as Jim Miller of Rolling Stone once noted, was “tied to surfing in name only.” Every artist who wants to make a dime with his work has to deal with commercial reality, but for Brian, the divide between business and creativity would become a vast chasm, resulting in lovely “art” songs on one hand and on the other, second-rate “commerce” songs that often rang hollow.

Over the long run, it would be impossible for all these songs to comfortably coexist under one banner, but for a brief time in the mid-‘60s, Brian would figure out a very elegant method through which to handle the art-vs.-commerce issue. He would do this not just because he wanted to, but because he had no choice. For as the year 1963 came to a close, the life that Brian lived as a young American working in the L.A. rock ‘n’ roll business was on the precipice of change.

On November 22, 1963, the President of the United States was murdered and a couple of days later Americans watched as the prime suspect was gunned down (or if you prefer, “whacked”) on live television. This was a shared, collective trauma, which is why Americans remember that it occurred, and where they were when it went down. As with the innumerable atrocities and obscenities that are now recorded for daily public absorption, we didn’t really understand what we were looking at. California historian Kevin Starr writes that the “the assumptions of the 1950s” had been firmly in place up until the assassination, but were now coming dislodged; that the decade of upheaval now recalled as “The Sixties” didn’t really begin until after this event.

This view is commonly accepted by those that lived through the era, and the Beach Boys’ music of ’61-’63 correlates with it. Stylistically, the Boys’ early songs are rooted in 1950s sounds like doo-wop, rhythm & blues, the Four Freshmen vocal blend and Chuck Berry’s rock ‘n’ roll. Thematically, they were perhaps more contemporary as surfing and car songs were fads of 1962 and ’63. Conceptually, “In My Room” was modern and forward-looking, while “Be True to Your School” could not have succeeded commercially without a prevalent “Fifties” culture.

The Beach Boys were on top in 1963. Surfing was cool, car songs were cool, and the Beach Boys had seamlessly merged different musical styles within a fresh West Coast packaging. As a rock ‘n’ roll group, they were unchallenged in America. As a male vocal group, they were rivaled only by New Jersey’s Four Seasons, a lineup of much older guys with a good in-house writing team. However, the Four Seasons’ Italian-American street-corner/social club vibe was even more of a ‘50s throwback. While still respecting the Four Seasons, the Beach Boys could happily view them as competitors.

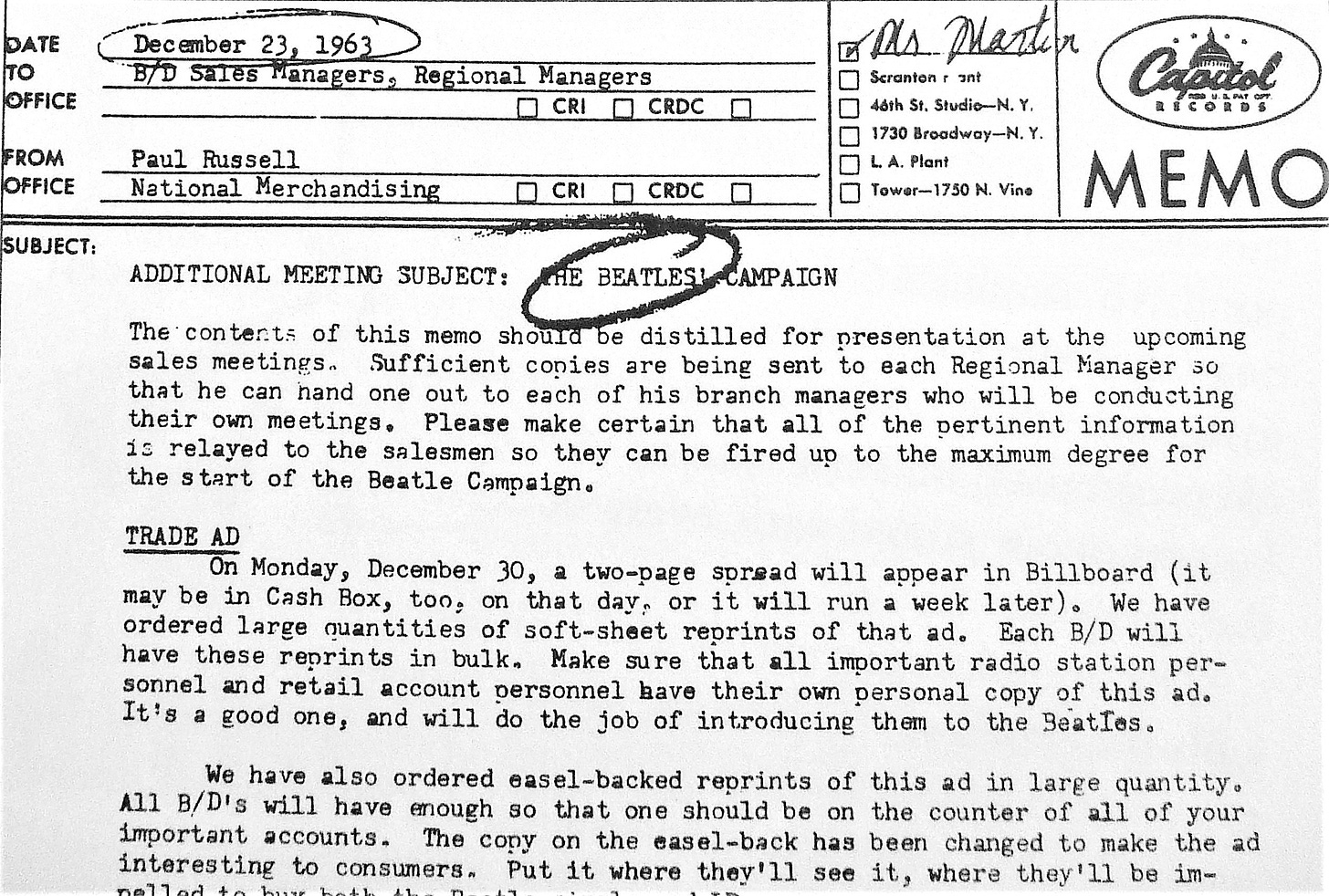

Meanwhile, the real threat to the Beach Boys’ preeminence was on its way from points farther east than New Jersey. During 1963 the Beatles had been releasing hits in the UK, but only by the end of the year was their American label, Capitol, ready and willing to promote them in the United States.

1964 would prove to be one hell of a year for the Beach Boys and Brian Wilson especially. Whatever path Brian was going to take, one thing was expected to remain constant: Murry would be right there with him in one form or another, indefinitely, as both father and manager. Murry was going to lead Brian, or more likely, follow closely on his heels. He could instruct or obstruct him, or do both at once. He could compete with Brian, “protect” him, and above all, continue to be the same man he had always been.

1964 would start with yet another conflict between father and son—the point of dispute this time being the Beach Boys’ new single. It would end with Brian wobbling at the brink of psychological collapse.

A History of Brian Wilson turns toward the critical year of 1964 in Part 16.

Selected References for Part 15

“Brian Wilson: 1974 Interview (The Beach Boys).” At YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WEeqwNl17YM (last accessed September 13, 2023)

Leaf, David. The Beach Boys and the California Myth. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1978.

Love, Mike, with James S. Hirsch. Good Vibrations: My Life as a Beach Boy. New York: Penguin/Blue Rider, 2016.

Marcus, Greil. “The Beatles.” In Anthony DeCurtis, James Henke and Holly George-Warren, eds. The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll. New York: Random House, 1992.

Pewter, Jim. “Brian Wilson Tells Jim Pewter All About the Early Days!” Bomp! Winter, 1976-77.

Riley, Tim. Lennon: The Man, The Myth, The Music—The Definitive Life. New York: Hyperion, 2011.

Simon, Alex. “Brian Wilson: Good Vibrations.” Venice, October 2002.

Starr, Kevin. Golden Dreams: California in an Age of Abundance 1950-1963. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Whitmer, Peter O., with Bruce VanWyngarden. Aquarius Revisited: Seven Who Created the Sixties Counterculture That Changed America. New York: Citadel Press, 1991.

Some may say there’s no real distinction between art and business-craftsmanship; that “Little Deuce Coupe” is just as artistically valid as “Caroline, No.” Or that “Caroline” was just as commercially motivated in 1966 as “Little Deuce Coupe” was in 1963, with the only difference being that “Caroline” stiffed as a single. Others might say that because this is the record business, anything anybody ever does is always done for business reasons first. “Kokomo,” “Surf’s Up,” “Catch a Wave,” “Ding Dang,” “Love and Mercy”: all of it is business, and let’s not pretend otherwise. And if you want to be an artist, get out of the business.

Or at a minimum, stay in the business making records, but keep your “art” to yourself. Which is what Brian was arguably doing as of 1970, at least with respect to one special piece. That year, Rolling Stone asked him about his unreleased song “Surf’s Up” (co-written with Van Dyke Parks), for which there was not even a finished recording that would have been suitable for commercial release. Brian was unenthused about fixing “Surf’s Up” within the frame of business: “Instead of putting it out on a record, I would just rather leave it as a song. It rambles—it’s too long to make it for me as a record, unless it were an album cut, which I guess it would have to be anyway… It’s so far from a singles sound—it could never be a single.” Possible translation: as a piece of art (a “song”), “Surf’s Up” is finished and complete. As a piece of business (a “record”) it does not exist, and that’s the way I want it.

This assumes that doing a song about school spirit was Brian’s idea. But loyalty too? Sure, absolutely possible, though it’s not totally inconceivable that he was influenced (encouraged, validated, browbeaten) by others who were more commercially-minded and/or of the authoritarian temperament. Still, Brian was calling the shots in these days—musically, conceptually, and to a significant extent, lyrically. So it’s on him.