From Brian Wilson’s point-of-view, the arrival of the Beatles in February 1964 demanded that some changes occur. For starters, Brian’s music with and for the Beach Boys had to evolve in some way. As discussed below, the Beach Boys’ Shut Down Volume 2 album—in terms of both its concept and music—concisely summarizes the problem facing the group. Were changes necessary in any other respect?

It seems they were. No later than the Beatles’ February appearance on Ed Sullivan, the Beach Boys had come to understand that retaining Murry Wilson as band manager wasn’t going to work out. If the Boys hadn’t already sensed this for a while, Murry’s conduct during the Australia tour in January made it obvious: the man had to go. But how to get rid of him?

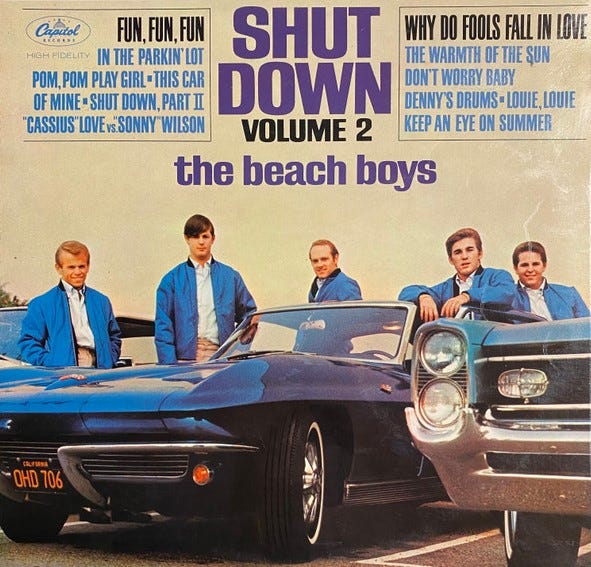

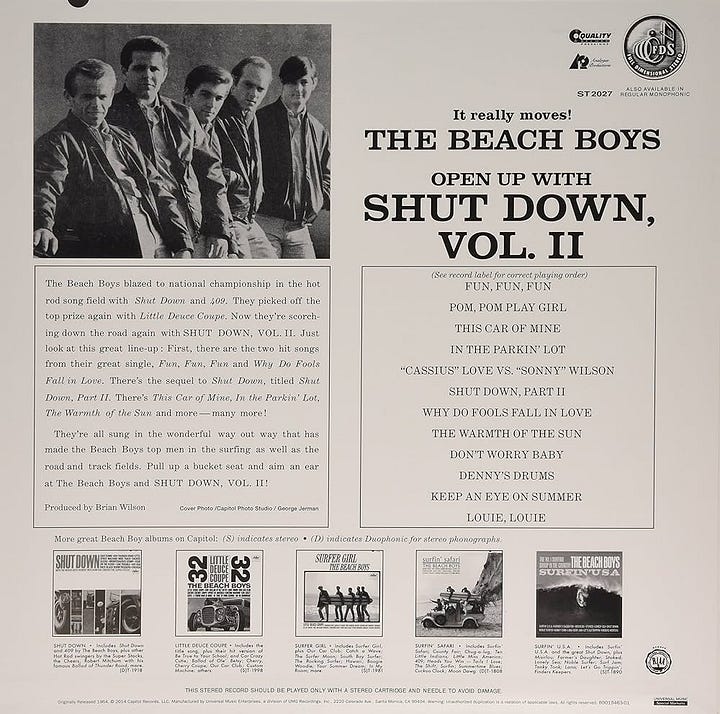

The Beach Boys’ first album of 1964, Shut Down Volume 2, was a post-Beatlemania release: it came out on March 2, a month after the Beatles shot to No. 1 with “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” and three weeks after the landmark Ed Sullivan performance. Yet Volume 2 was, in substance, a pre-Beatles album. The writing of some of the songs went back to 1963 and the meat of the album was recorded in January, before “I Want to Hold Your Hand” entered the singles chart. In other words, the Beach Boys recorded (most of) Shut Down Volume 2 while blissfully ignorant of the imminent Beatle invasion.

By the time Volume 2 was conceived, written, and recorded, the Beach Boys had ceased to be just a “surfing” group. They had established a secondary identity as a car band. During the Surfin’ Safari era of mid-1962, “409” had been the group’s first car song, but the Beach Boys didn’t really establish their car-cred until the spring of 1963 with “Shut Down,” the popular B-side of the “Surfin’ U.S.A.” single that was distinguished by lyricist Roger Christian’s vivid description of a drag race.

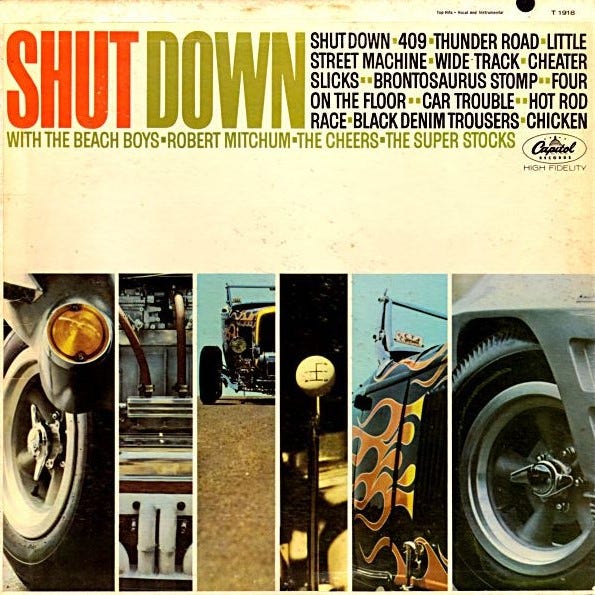

In June 1963, Capitol Records leveraged the success of “Shut Down” by slapping together an entire compilation album—titled, naturally, Shut Down—that was presented as a sampler of car songs and instrumentals from a variety of performers. The Beach Boys were represented on the album with reissues of the title track and “409,” which at that point were the band’s only car songs.

Beach Boys cuts aside, the Capitol Shut Down compilation (aka “Vol. 1”) was pretty much crap. Yet by August it managed to reach No. 7 on the album chart, an improbably strong performance made possible only by Capitol’s exploitation of the Beach Boys’ name and the title of one of the band’s hot new songs. Luckily for the Beach Boys, their inclusion in Capitol’s Shut Down hustle didn’t seem to do them much harm, for at the same time Shut Down was peaking on the album chart, the Beach Boys’ new car song, “Little Deuce Coupe” was doing quite well as the flipside of the “Surfer Girl” single. The Boys followed up by going back into the studio to record still more car-themed tunes that would eventually appear on the Little Deuce Coupe album in early October. Then came the anomalous “Be True to Your School” single (through which, as suggested in this post, Brian may have been trying to break out of the surf-and-car rut), followed at year’s end by the classic Christmas single “Little Saint Nick”—basically a revamped “Little Deuce Coupe,” in which the band reimagined Santa’s sleigh as a hot rod.

All this goes to explain the conceptual presentation of Shut Down Volume 2. If it had made sense for the Beach Boys to pose as surfers while singing about the beach, why couldn’t they pose as drag-racing grease monkeys while singing about cars? Here, in the waning days of their pre-Beatles existence, the Beach Boys (with Capitol’s encouragement and/or guidance) were presenting themselves as a tough car club—with matching jackets—ready to “shut down” any musical competition (such as the Four Seasons). Shut Down Volume 2 bore the same relationship to the Little Deuce Coupe album that Surfer Girl had to Surfin’ U.S.A.: it was an album that intentionally built on the theme introduced by its predecessor, solidifying the Beach Boys’ connection to the prevailing musical fad.

This didn’t mean there wasn’t great stuff on the album. In addition to “Fun, Fun, Fun,” Volume 2 featured two notable songs that have proven to be among the Beach Boys’ very best: “The Warmth of the Sun” and “Don’t Worry Baby.” The first, written by Brian Wilson and Mike Love, was another fine ballad with a traditional triplet cadence, an arresting chord progression, and mature, writerly lyrics. With “Don’t Worry Baby,” Brian (with Roger Christian credited as co-writer) repurposed the shopworn drag-race concept to craft what has proven to be a very significant song that deals with competition, fear, doubt, and how love provides a sense security. “Don’t Worry Baby” was in fact a complete inversion of Wilson-Christian’s “Shut Down.” The very same drag race described in the earlier tune was revisited from the racer’s internal, emotional perspective. Of course, the listener needn’t (and maybe shouldn’t) dissect the thematic elements of “Don’t Worry Baby” to enjoy it; the main thing was that it sounded good. As with “In My Room,” the deeper meaning of the song is felt by the listener, not shoved into his consciousness.

In spite of these advancements, as an overall collection Shut Down Volume 2 was barely an improvement (if at all) on the Surfer Girl and Little Deuce Coupe albums. “The Warmth of the Sun” and “Don’t Worry Baby” were at this point presented only as low-profile album cuts, alongside lesser stuff like the blown-up rearrangement of “Louie Louie.” There was Brian’s Phil Spector-influenced reading of the ‘50s nugget “Why Do Fools Fall In Love”—more grandiose than the original, but certainly not any better. “This Car of Mine” paired the shuffle-groove of “Little Deuce Coupe” and “Little Saint Nick” with the sentimentality of “Ballad of Ole’ Betsy.” The replacement of Mike Love’s swaggering vocals with Dennis Wilson’s cuddly sincerity made it kind of endearing, but the song was filler and Brian didn’t put much care into it. Two high-school portraits, “Pom Pom Play Girl” and “In the Parkin’ Lot” were musically inventive, well-produced, and probably not as embarrassing for the teen fan of early 1964 as they would be for listeners of later years. Still, those tunes were forgettable, surviving mainly as evidence of why Brian Wilson needed the Beatles to kick him in the ass.1

Notwithstanding the album’s shortcomings (which are in any case most apparent only in hindsight), it was still the individual recording—the single—that really mattered as a group’s most important musical statement. During the week of March 21, the irresistible “Fun, Fun, Fun” reached its peak at No. 5. The Beatles occupied the top three slots with “She Loves You,” “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and “Please Please Me.” (The Four Seasons had No. 4 that week with “Dawn.”) The confident young car-clubbers pictured on the cover of Shut Down Volume 2 had unwittingly been on the brink of extinction; they were the very sort to be eradicated by the invasive British species. However, the solid performance of “Fun, Fun, Fun” kept the Beach Boys in the game during the first blast of Beatlemania.

Fast-forward a couple of weeks to April 2, 1964: with Shut Down Volume 2 in the stores for only a month, it was time to start sessions for the follow-up to be released in about three months’ time, during summer. This would be the Beach Boys’ first batch of songs to be written and recorded within a post-Beatles reality, and the group had to deliver.

The early sessions were for “I Get Around,” a song that would be the showpiece of the album and the main summer single. Brian had sketched it out on the upright piano at his girlfriend Marilyn’s family home in the Fairfax district and had an idea in his head of what the finished product was going to sound like. To do the job, Brian was going to use the Beach Boys singing and on their respective instruments plus a few studio pros adding critical percussion, guitar, bass and horn parts. And of course, Murry Wilson would be present in the studio for the session—not only in his formal capacity of business manager, but also that of unofficial co-producer and father-protector-controller.2

Whatever it was that occurred between Murry and Brian during the recording of “I Get Around,” it was ugly. As Brian tried to lead the session, Murry taunted, insulted, and attacked him verbally. A mawkish, Father-Knows-Best reflex dictates that Murry did this to “drive” Brian and get the best out of him, but everything that is known about Murry Wilson shows that he was not a dad who merely “criticized” his son, constructively or otherwise. In reality, Murry was driven to compete with Brian, fight him, abuse him, control him and exploit him. Alternatively—or preferably, even—he would break Brian decisively and simply destroy him. Obstructing Brian’s creation of music was the most effective way for Murry to accomplish these goals.

Murry hadn’t liked “Fun, Fun, Fun” and he now had problems with “I Get Around,” a song that offended him.3 Murry chipped away at Brian’s confidence, denigrated the music, and ordered Brian to cancel the session. Mike Love has reported that Murry went into the studio control booth and ordered Brian to “get out of the way.” Brian refused.

A number of witnesses (e.g., Mike Love, session drummer Hal Blaine) have recalled hearing Murry insult Brian and his music during this era, but what these people couldn’t know was that Murry’s cut-downs, as bad as they were on their face, also had a subtext reaching back to Brian’s childhood. Whatever emotions Brian was experiencing during this confrontation were not simply the immediate result of Murry’s actions at that particular moment; this wasn’t just some disagreement that flared up about the proper way to record a song. Rather, it was everything—what this man had been doing to him his entire life.

Between Murry and Brian, there was an intimate and secret personal history of grotesque parental violation that was always implicated in their current-day interactions. Recalling the fateful “I Get Around” conflict in his 1991 autobiography, Brian said that Murry specifically warned him to “remember who you’re talking to.” This is a believable account. If a third-party outsider ever heard Murry say that to Brian, it would have meant something like, “don’t talk to your father that way.” But in this case, “remember who you’re talking to” translates to, among other things, remember what I did to you. I made you shit on a newspaper, so don’t ever forget what you really are. Some accounts of the session depict Murry shoving Brian and jabbing him with his finger, which too would have been a way of sending Brian back to childhood—like Biff Tannen in the movie Back to the Future, still rapping his knuckles on George McFly’s head after thirty years, in McFly’s own home.

It would have injured and enraged Brian to be denigrated by his father, particularly during an important session taking place in the midst of Beatlemania, when Brian’s career, and that of the Beach Boys, was on the line. And it wasn’t just Brian who was feeling it. Murry took aim at Dennis too, driving Dennis to punch a hole in the studio wall in a spasm of frustration and impotent rage. (It’s possible Dennis was actually taking a swing at Murry and missed.)

Murry needed to be shut down, with merciless finality. That was theoretically possible, but in practice extremely difficult if not impossible, for a bunch of reasons. We can idly speculate that there was a part of Murry—festering somewhere deep within his tormented psyche—that sought this from his firstborn son all along: do something to put me out of my misery, please.4 Yet how to make him go away? After all, Brian wasn’t even going to put Murry on the deck as Gary Usher had once counseled him to do.

Something had to be done. At the barest minimum, the time had come for Brian to assert dominance within the physical space where music was being created. For Brian, the professional recording studio was the adult version of the humble music room back in Hawthorne. The studio was his optimal environment, his “room,” the place where he expressed the healthiest and most capable part of himself. Murry was not going to relent until he either conquered that territory, or wrecked it completely.

This continues in Part 18

Selected References for Part 17

Brian Wilson: Songwriter 1962-1969. Produced by Prism Films, Chrome Dreams Media. Sexy Intellectual Productions, 2010.

Doe, Andrew. “Shows and Sessions 1961-2024.” Bellagio10452.com. At: www.bellagio10452.com/gigs.html

Gaines, Steven. Heroes and Villains: The True Story of the Beach Boys. New York: Dutton/Signet, 1986.

Granata, Charles L. Wouldn’t It Be Nice: Brian Wilson and the Making of the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds. Chicago: A Cappella Books, 2003.

Love, Mike, with James S. Hirsch. Good Vibrations: My Life as a Beach Boy. New York: Penguin/Blue Rider, 2016.

Williams, Paul. Brian Wilson & The Beach Boys: How Deep Is The Ocean? New York: Omnibus Press, 1997.

Wilson, Brian, with Todd Gold. Wouldn't It Be Nice: My Own Story. New York: HarperCollins, 1991.

"Pom Pom Play Girl” was a song on which the Beach Boys returned to the high-school-football-game scenery of “Be True to Your School.” It was one of four tunes the Beach Boys recorded after the Beatles’ Ed Sullivan broadcast had opened the floodgates for Beatlemania. Who knows what Brian was thinking as he cut “Pom Pom Play Girl,” but it’s the most puerile song on Shut Down Volume 2. Could this have something to do with Brian’s decision to assign the lead vocal to the baby of the group, high school-aged Carl Wilson?

It goes without saying that Murry’s studio presence had been at best superfluous. People like session drummer Hal Blaine and recording engineer Chuck Britz have basically said he was out of his depth in the studio. There are reports (rumors?) that Brian once went so far as to install some kind of fake mixing console for Murry to play with during sessions while Brian proceeded to actually produce the records.

Murry’s subjective inner feelings about “I Get Around” are further discussed in Part 19 (“How Do You Fire Your Dad?”) of the History of Brian Wilson post-series, and comprise the main subject matter of Part 21 (“The New Rays of the Rising Sons”). (click links to read.)

As terrible as it is to contemplate, actual murder—parricide—does indeed occur from time to time in families like this. Parricide refers to the murder of a close relative, often one’s parent. Research (“data”) in this field depicts the most common parricidal scenario (as it occurs in the United States): a parent—often the father—who maintains the outward image of a hardworking, successful, and law-abiding wage-earner—engages in a chronic pattern of senseless, sadistic persecution of his child (or children) behind closed doors, over a very long period of time. The child is effectively trapped and defenseless, as the mother refuses to intervene on his or her behalf. The reality of the child’s life is typically denied (disbelieved, rationalized, sentimentalized) by family and outsiders alike. Having reached a breaking point over the course of many years, the child—typically a teenager who is white, male, middle class, and otherwise well-behaved with no criminal record or history of juvenile delinquency—at last explodes with lethal vengeance. See Paul Mones, When A Child Kills: Abused Children Who Kill Their Parents (Simon & Schuster, 1991); Kathleen M. Heide, Why Kids Kill Parents: Child Abuse and Adolescent Homicide (Ohio State University Press, 1992).