On the Pet Sounds album of 1966, Brian would sing, “I keep looking for a place to fit in / where I can speak my mind.” If such a place ever existed for Brian—in the concrete, physical world— it was the professional recording studio. Pet Sounds itself would be evidence of that. And looking back retrospectively, it seems that in 1963, three full years prior to the recording of Pet Sounds (and “I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times”), Brian was gravitating toward that place, and away from life as a touring musician performing live across the country. For Brian it was a matter of both personal well-being and creative necessity.

By mid-1963, as the Beach Boys were riding the first wave of nationwide success, circumstances had evolved to benefit Brian in two ways. First, Brian had (unconsciously, or instinctively) devised a sly way to exempt himself from touring with the Beach Boys: just don’t tell anybody that you’re not going to show up for duty and instead invite Al Jardine back into the band to perform in your place. Second, Brian was winning greater autonomy in the studio as the Beach Boys’ record producer.

While Brian’s father Murry strongly objected to Brian’s reluctance to tour, he was nevertheless willing to help liberate Brian from Capitol’s studio oversight. (Murry would never be so willing to do the same with respect to his own control over Brian.) These developments were discussed in the preceding entry of A History of Brian Wilson.

By the end of summer 1963, the constant intra-group turbulence manifested itself in a dispute between Murry Wilson and young rhythm guitarist David Marks. By October or so, Marks was out of the band, and Brian was forced back out onto the road. For Brian, this was an unwelcome turn, but the good news for him at this time was that Capitol Records was willing to allow him, at age 21, to be sole producer of the Beach Boys’ records. The band’s second album of 1963, Surfer Girl, had been the first to bear the credit, “produced by Brian Wilson.”

Part 14:

The Beach Boys’ third album of 1963 would be called Little Deuce Coupe. Sessions had already begun before the previous album, Surfer Girl, was released, and Capitol Records would quickly put out Little Deuce Coupe less than a month after Surfer Girl. The fact that these two albums would appear within about three weeks of each other shows that Capitol had no qualms about saturating the market with Beach Boys “product.” The fear was what would happen if the label didn’t do that.

The Beach Boys had proven to be a good investment for Capitol, but it could only be in the short-term. Anyone could see that no matter how talented, this was a fad group, and as such, its lifespan would be short. The label’s natural strategy was to pump-and-dump, extracting maximum revenue before the kids got sick of the Beach Boys and either grew up or moved on to something else. The group had successfully sold itself as “Beach Boys”—boys from the beach—and had lived up to the name. Surfer Girl had been their best-sounding collection of songs to date, and it relied heavily on the beach hook. Most of the album’s tracks evoked beach culture, with five of them using the word “surf” in the very title.

In these days, Brian would have openly admitted that the Beach Boys made “teenage music.” He never had a problem with that, and was probably even proud of it; a few years later he would exalt the idea of youth music with his description of Smile as a “teenage symphony to God.” What Brian in 1963 may have been less willing to admit was that he was making fad music. However, notwithstanding the Beach Boys’ talent and the quality of the records, he basically was. And that was perfectly okay, at the time. It was even to be expected.

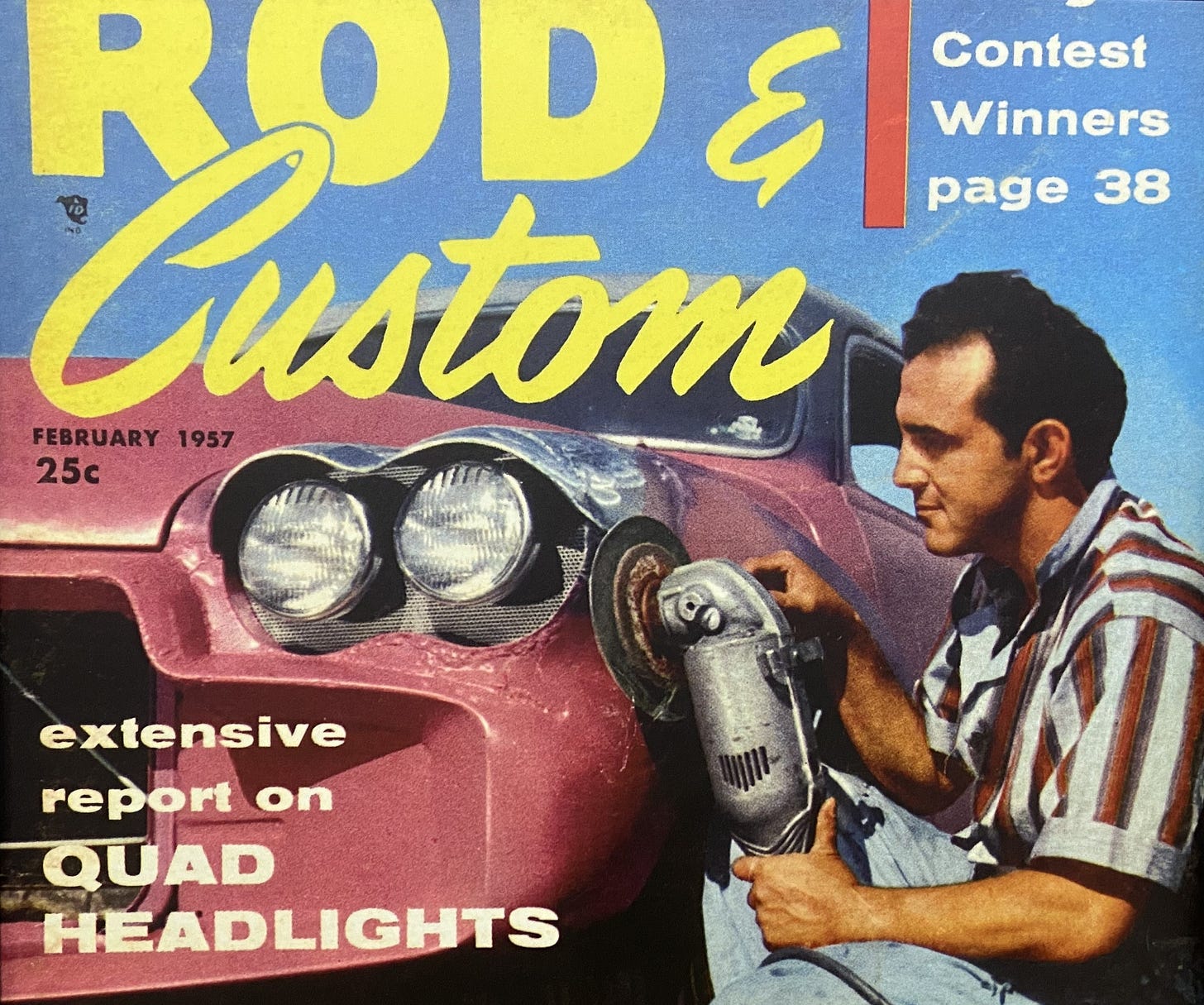

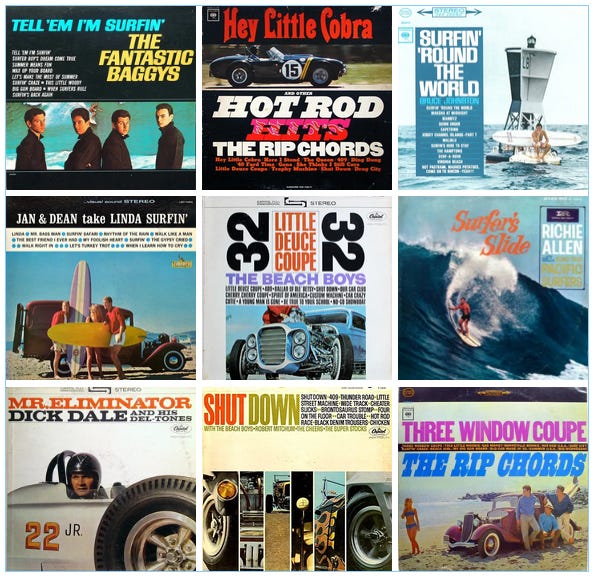

As of 1963, the Beach Boys-Capitol team was purposefully working according to the fad model, and doing so quite shrewdly: even before reaching the heights of the surf craze with “Surfin’ U.S.A.,” the Beach Boys had already brought lyricist and car-aficionado Roger Christian into the organization for the express purpose of writing car-themed songs with Brian. In other words, as of early 1963, Brian, Murry, the Beach Boys and Capitol were aligned under a general plan of action: a bunch of beach songs, the sameness of which to be mitigated by the occasional car song. Or, alternatively, the plan was more bifurcated: a barrage of beach-and-surf tunes to be followed by a barrage of car songs, in effect replacing one fad with another. Within the fad-model of songwriting and record-making, this is what constituted creativity, flexibility, and variety.

So it might not have been only Capitol’s corporate shortsightedness that prompted the release of two Beach Boys albums within one month. Maybe it could have been justified as a rational strategy for the marketing of a fad group like the Beach Boys—whose success was seen as attributable not just to the talent of the members, but the trends and crazes they sang about. The general idea: before the kids in the audience can take even a moment to realize that the Boys had been hawking the same theme over and over (and on Surfer Girl, running it into the ground), strike while the iron is hot, hitting ‘em with a bunch of fun records about cars. Maybe. In any case, it seems that sound business judgment dictated that it was time for the Beach Boys to get off the beach and into the auto-shop, as others were doing, even surf guitar king Dick Dale.

Going back to “Rocket 88” and the beginnings of rock ‘n’ roll itself, the car-song (often written to capitalize on built-in sexual metaphors) has always been a natural fit for the music. Any number of well-known and respected popular artists—Chuck Berry, Bruce Springsteen, NRBQ, Joni Mitchell, Prince, Van Halen, Ry Cooder, Harry Nilsson, Neil Young and the Beatles—have done fine songs that trade in car & driving imagery. But only the Beach Boys did so many of them in so compacted a period, for during the early Beach Boys peak of 1962-63, car songs were indeed an outright fad. And again, the Beach Boys were then a fad group—seemingly well-positioned to both catalyze new teen fads and then capitalize on them with a batch of tunes written on the theme in a very literal manner.

With Gary Usher, Brian had already written “409”—not the best Beach Boys car song, but maybe the purest. Brian also wrote a couple of car songs with Mike Love, and maintained his partnership with Roger Christian for songs like the hit “Little Deuce Coupe” that rolled off the assembly line outfitted with gearhead lingo. The boundaries of the Brian-Roger collaboration were more clearly delineated than those with Usher, and Christian seems to have gotten along well in the Beach Boys organization; he later remembered his song publisher Murry Wilson as “one of the finest men I’ve ever known.” Over a period of maybe no more than six months, the Beach Boys would do as many as 15 car-themed tunes, including their widely-known Christmas variation, “Little Saint Nick.”

This was the practical, business-driven model upon which the Beach Boys established their popularity. It would prove to be a problem for Brian Wilson, particularly between 1964 and 1967 when he would try, in fits and starts, to steer the Beach Boys toward a musical stance that could be taken more seriously. 1963, however, was a time during which fad songs still made sense. Indeed, the entire genre of rock ‘n’ roll itself could then be reasonably heard as a transient youth-fad (not unlike the way people would view rap/hip-hop in the mid-1980s). It is worth noting further that drag racing, cruising, dry-lake speed trials and street-rod customization were, like surfing, very real components of Southern California boom-culture. As with the surfing songs, this inherently restrictive—and yes, financially motivated—subject matter sounded genuine when expressed in the voices of Southern California’s Beach Boys. In these days Brian and the Beach Boys had both the opportunity and ability to make commercial pragmatism sound utterly pure.

The Little Deuce Coupe album featured a bunch of car songs, some of which are fine examples of how musically inventive Brian’s music had become and how good the Beach Boys sounded on record in the fall of 1963. Still, most of these songs would never have the staying power of an “In My Room.” Any song that adhered to an obviously fad-driven car concept would have difficulty living and breathing for listeners of later years.

Yet nobody really cared about that. A normal, sensible person was unlikely to have given a thought to whether future listeners of say, 1966 or 1969 (let alone 2025) would be able to relate to songs like “Little Deuce Coupe” or “Custom Machine.” Brian took his music seriously, but that didn’t mean that it was, by default, serious music. It wasn’t.

Today, about 60 years onward, the Beach Boys’ music is well-respected; the band’s best records are commonly recognized as among the best ever made, their vocal harmony understood to be inimitable. In his later years, Brian Wilson himself received medals, was inducted into various Halls of Fame, and was name-checked with admiration by symphony conductors. People now consider him to have been a genius. In short, a time would eventually arrive when Beach Boys music could be a matter of serious inquiry, mainly because Brian Wilson himself would be seen to have done enduring work—some of it indeed very serious—worthy of study and historical recognition.

This time had most certainly not yet arrived in the 1960s, especially during the surf and car song-era of 1963. While the Beach Boys were then recognized as leaders in their class, the class itself was fairly circumscribed.

It wasn’t music, but success in the music business—the selling of records—that was serious. As it ever was or would be, the game was to “move units,” and no matter how well-made the recordings were, they were disposable. Capitol Records handled the Beach Boys not as art or even craft but a volume business; whatever the creative process might have entailed was irrelevant. The prospect of someone like Brian Wilson wanting to express something on record—a feeling, an opinion, an insight—was scarcely conceivable. That was the territory of someone like the serious young folk musician Bob Dylan out in New York, or better yet, Peter, Paul and Mary, who could take Dylan’s message on “Blowin’ in the Wind” and get it on the hit parade at Billboard No. 2.1

For their part, Brian and the Beach Boys wanted their stuff to sound better than the competition, but they had all entered the business with the goal of chart success. They were naïve in many ways but did seem to know from the start that this was indeed a business (which therefore did not differ entirely from their fathers’ trade in sheet metal, lathes, and drill presses). Brian had written as a musically creative businessman since the very beginning, and had struck out when he strayed from the beach or blacktop. The trick then, was simple to describe, but hard to achieve: stay ahead of the curve with next fad that the kids were going to be into, and then do the best work possible against that constraint.

Equipped with talent and good timing, the Beach Boys were able to do this in 1962 and 1963. They made the best surfing and car songs of the era. Yet for Brian, things were going to become more complicated than the already-challenging game of reading trends and scoring hit singles.

For more, see Part 15 of A History of Brian Wilson

Return to preceding chapter (Part 13)

Selected References for Part 14

Hoskyns, Barney. Waiting for the Sun: Strange Days, Weird Scenes and the Sound of Los Angeles. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1996.

Leaf, David. The Beach Boys and the California Myth. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1978.

Selvin, Joel. Hollywood Eden: Electric Guitars, Fast Cars, and the Myth of the California Paradise. Toronto: House of Anansi, 2021.

Bob Dylan was then understood to be a “folk” artist, not a rock ‘n’ roller or pop act. It was acceptable in the business for a folker like Dylan to be “serious” but he couldn’t be “pop” at the same time. Therefore, if “Blowin’ In the Wind” was to be a hit, another act, Peter, Paul and Mary, was needed to step in and cover the tune in a more pop-oriented style. (The canny Albert Grossman managed both acts.) Meanwhile, though Brian Wilson was recognized and respected in the business, it was only as a maker of commercially successful but insubstantial teen and surf records. Brian was presumed to have absolutely nothing to say—and moreover, to not even want to say anything. (And if he did, then what the hell was he doing making all that dough with surf and car records in Hollywood?) These were the presumptive rules, and they were workable and acceptable to Brian as of this point in mid-1963. However, by no later than the middle of the following year, Brian would begin gravitating toward more mature, introspective themes, only to be confronted with the reality that they were unsuitable to be delivered as “teenage music” under the Beach Boys name.