Before returning to the goings-on of 1964, here is the second part of this comment on “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” and other songs on growing up and the passage of time.

Part 1 of this comment listed several songs that are about the transition from adolescence to adulthood and the passing of time. It was a loose compare-contrast exercise; a means to think about what, if any, other songs contain the same unique combination of characteristics as the Beach Boys’ “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man).” Most of the songs dated from the mid-1960s, and were written by major artists of the rock ‘n’ roll/singer-songwriter era.

Part 2 touches on the distinction between Brian Wilson and some of these other musicians, with a focus on how Brian and the Beach Boys were perceived within the mainstream rock ‘n’ roll culture of the late-1960s through the 1990s. The post concludes with some thoughts about a possible connection between the Beach Boys’ image problem and Brian Wilson’s style of songwriting and production—an approach that happens to be demonstrated quite well in a recording like “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man).”

Back to first part of “Child/Adult”

Second Part:

The previous post featured a gallery of six photos in which a young Brian Wilson was grouped alongside other well-known musicians:

The image was meant to convey a basic equivalence between Brian (pictured at around 21-years-old, in his parents’ house and probably several months before making “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)”) and other famous songwriters, with the main point of similarity being how, during the 1960s, they all wrote or released songs about growing up and/or the adult-child divide.

However, at a more specific historic or cultural level, this collage is not entirely accurate. As either an individual musician or stand-in for the Beach Boys group, Brian Wilson doesn’t quite fit with the others. As readers probably know, Brian and the Beach Boys have, for the better part of a half-century, not been viewed in quite the same way as Dylan, Townshend, the Beatles, Byrds, Neil Young, et al.

This is not to say Brian’s music with and for the Beach Boys hasn’t always had a place in the rock ‘n’ roll culture.1 It has. However, that culture (as something distinct from rock ‘n’ roll music itself) came into being only in the late 1960s, the point when rock ‘n’ roll first became recognized as an established form of popular music instead of a transient teenage fad that listeners were expected to grow out of. This occurred while the Beach Boys were in the throes of reputational and commercial decline. By the time rock ‘n’ roll “grew up,” the Beach Boys were off the scene, relegated to, at best, a historical position in the culture.

For at least 30 years (approximately the mid-1960s to the mid-1990s if not later) the band remained known for what it had done in the first half of the 1960s, not for what it did (or didn’t do) in the latter decade, or in the Seventies, Eighties and beyond. The Beach Boys had been good enough, and popular enough, to be enjoyed retrospectively: from time to time, they would experience a resurgence when, for whatever reason, a nostalgia-craze kicked in and the public wanted to go “back to the beach”—as it did in the mid-1970s, and for a moment the late 1980s when “Kokomo” became a No. 1 hit. With a handful of exceptions (like “Good Vibrations”), these periodic revivals never concerned any music Brian Wilson or the Beach Boys did after 1965. It took a long time for even Pet Sounds to find a mass audience and become widely recognized as one the best albums of the entire rock ‘n’ roll era.

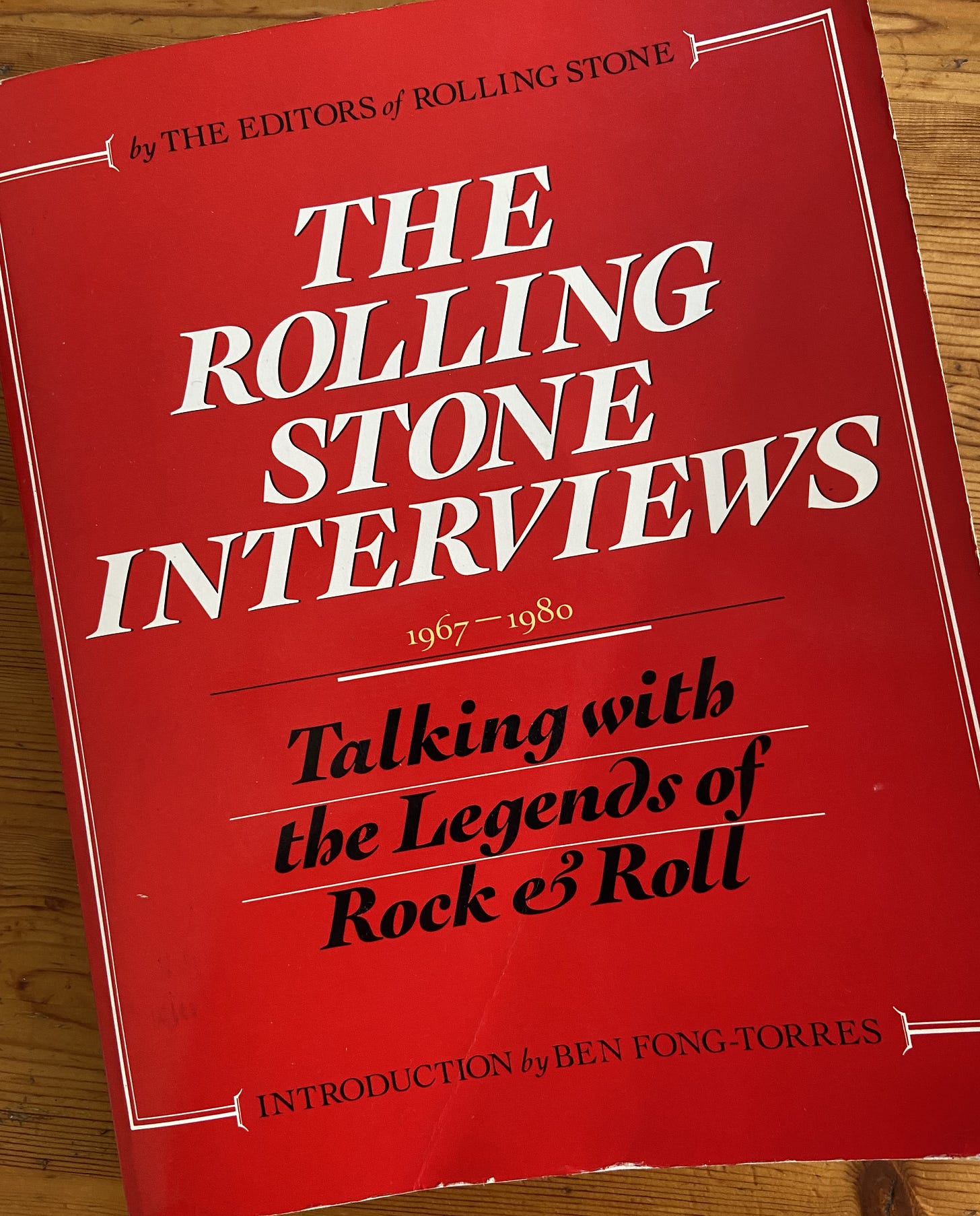

Even in their recognized position as beloved historical figures of rock ‘n’ roll, neither the Beach Boys nor Brian Wilson were viewed, in the main, as being terribly important. As evidence, here is a book I stumbled on recently (July, 2024) at a used record store:

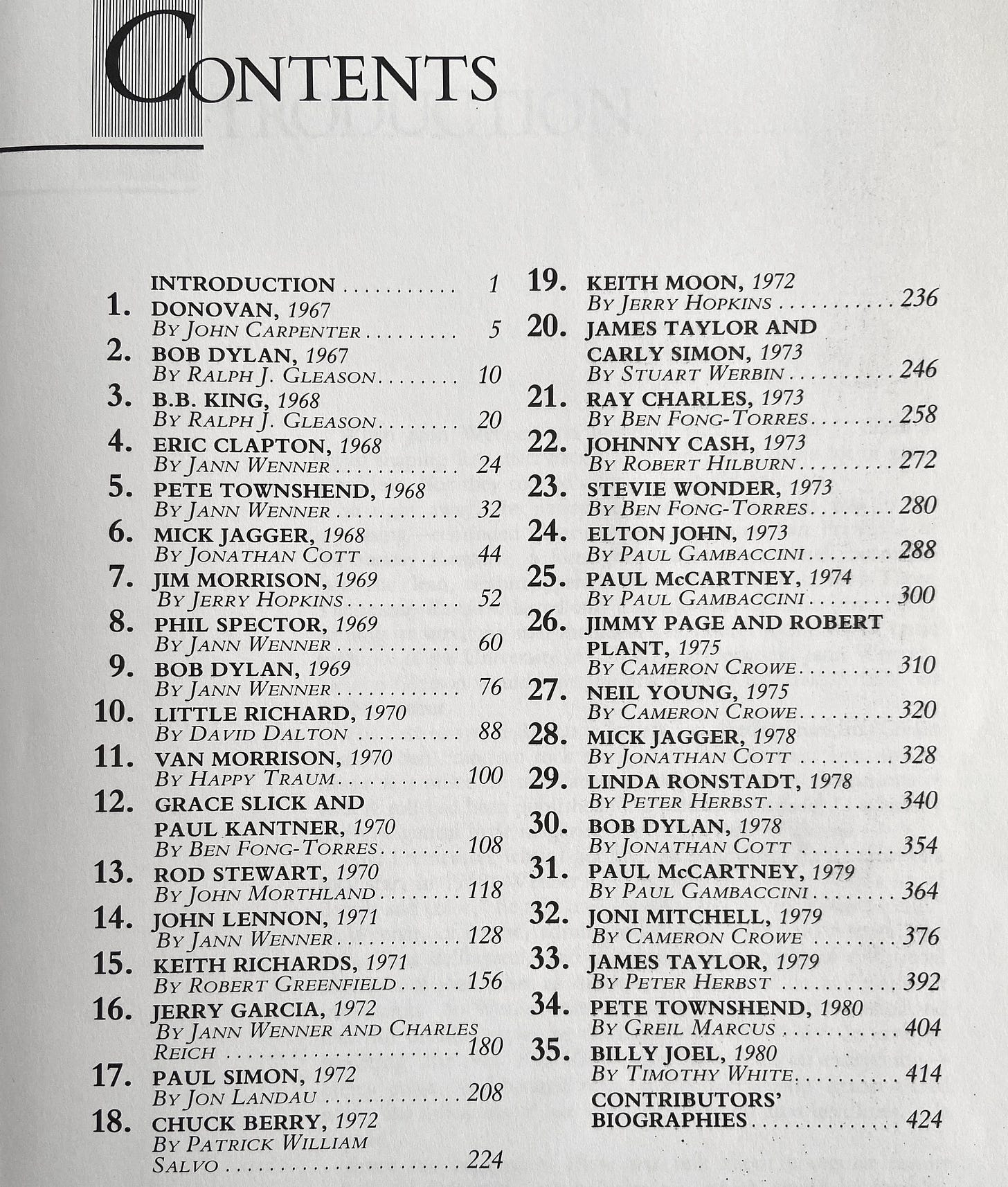

This book was published in 1981. Here is its list of interviews:

If this was intended as a representation of the most significant musicians and songwriters of rock ‘n’ roll (as of 1981), we can now say that Brian and the Beach Boys are conspicuously absent. (So is Ray Davies of the Kinks, another group that (for different reasons) failed to remain in step with the musical and cultural changes of the late ‘60s.) By itself, the omission of a Brian Wilson/Beach Boys entry doesn’t prove that their music had been downgraded, but nevertheless indicates that neither Brian individually nor the group as a unit rated inclusion among this class of artists.2

Conventional wisdom locates the origin of the problem in mid-1967, when Brian failed to deliver a completed Smile album and the Beach Boys backed out of the Monterey Pop Festival, the event that effectively served as the coming-out party for Sixties rock culture. That’s true, but the sunny, Southern California image that had worked so well for the Beach Boys between 1962 and 1964 (and extending, improbably, into 1965 with “California Girls”) had already begun to exhaust itself before Monterey.

On March 17, 1966, the Beach Boys (whose most recent single, the regressive “Barbara Ann,” had peaked at No. 2 at the end of January) headlined at the University of Dayton (Ohio), during their first collegiate tour. John Sebastian and his band the Lovin’ Spoonful was the opener, and received a better audience response.3 Occurring at a time when Brian was in Los Angeles working on Pet Sounds, and before “Good Vibrations” or the Smile drama, this is one of the earliest indications that the Beach Boys would fall from the public’s good graces in the second half of the 1960s. According to Smile lyricist Van Dyke Parks, later that year (around the time “Surf’s Up” was written), Dennis Wilson reported that the group had been jeered during a performance. It’s possible that the Beach Boys’ absence from Monterey in 1967 only confirmed something that was already in motion, if not predestined.

But why? There are many, many reasons (far too many to explore here) for the Beach Boys’ exclusion from rock’s upper echelon. Suffice to say it has something to do with the musical, aesthetic and cultural preferences of a couple of generations of rock ‘n’ roll fans who, for reasons both good and bad, rejected the Beach Boys and what they had to offer. There’s plenty of evidence too, that the Beach Boys in fact preferred to be associated with the past: a year after the Monterey festival, they released their beach song “Do It Again,” which wasn’t really about surfing or going to the beach, but returning to the beach from which the group supposedly originated. That tune nicely encapsulated the idea that the Beach Boys’ present identity was to be found in their past. And the public agreed—the mediocre “Do It Again” did tolerably well as a stand-alone single (No. 20) while at that very same moment, the group’s outstanding and properly up-to-date album Friends bombed miserably.4

It wasn’t only a matter of musical and lyrical substance, but form too—the way the Beach Boys presented and performed their music. Even at their best and most popular, the Beach Boys always stood apart from whatever could be safely categorized as “rock ‘n’ roll,” a genre which by the late ‘60s was defined by two main reference points: (1) the rock-band prototype of the Beatles and (2) the singer-songwriter model of Bob Dylan. Neither the Beach Boys nor Brian Wilson ever fit comfortably within either category.5 In the early 1970s, at a time when the Beach Boys seem to have had no other options, they tried to reconstitute their ungainly organization as a “rock band,” but it didn’t work. The Beach Boys had never been, and never could be, that kind of group.

Finally, there’s the issue of maturity. Brian and the Beach Boys built their name not just by writing and performing for a teenage audience, but by playing to them as teenagers, pandering to them, purposefully crafting songs that reflected a presumed “teenage lifestyle.” It was a double-edged sword. It was great when it worked, but even during their successful years, the Beach Boys were like Woody, Buzz Lightyear and the other toys in Toy Story, always on the precipice of rejection and obsolescence once their “owners” (fans) grew up, found a new toy (fad, craze, new band) or otherwise got sick of playing with them.

Because the Beach Boys made great teenage records so convincingly, it was inconceivable that they could ever do anything else. The fans may have loved the Beach Boys, but didn’t respect them or trust them to make music that could communicate an evolving, young-adult sensibility. (Pet Sounds was far too sophisticated and made no sense to the fans as an album; Smile would have been even further beyond; Smiley Smile signaled failure to keep up with the times.) In the late 1960s, the kids grew up and took their new rock music along with them. Rock ‘n’ roll would survive, but the Beach Boys didn’t quite make it. They got left behind, in childhood.

From a Brian Wilson perspective, the irony is especially wicked. Brian, after all, was the one who first tried to direct the kids toward adulthood, way back in August of 1964, on “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man).”

At that point, Brian was looking to break out from the restrictive teen genre, but it was tricky: the underlying subject matter of “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” was sophisticated, but the presentation was not. Brian was still writing down to the kids, even as he was trying at the same time to pull them (and himself) forward, toward maturity.

In the end, “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” may not have landed the way Brian hoped. It somehow got to No. 9 on the singles chart, but had no life whatsoever, becoming, at best, an interesting anomaly within the Beach Boys ‘60s discography. As Beach Boys music, it was easily overshadowed by the more well-known Beach Boys hits of 1963, ‘64 and ‘65. As a song about growing up, it became overlooked—at least when compared to the songs listed in the first part of this comment.

The existence of those songs indicates that coming-of-age or passing-into-adulthood would become an acceptable theme among the rock ‘n’ roll/singer-songwriter crowd and its fans—provided that it was treated with some combination of artistry, musical quality, sincerity, and coolness. Even better if the song was delivered from the appropriately mature, retrospective outlook of a young adult.

For the rock ‘n’ roll/Rolling Stone generation(s), “Sugar Mountain” and “The Circle Game” are perhaps the most widely-known and celebrated tunes on this theme. Starting from the late 1970s, anytime Neil Young broke out his Martin guitar and started picking the opening phrase of “Sugar Mountain,” an entire arena of rock fans would erupt in cheers.6 “The Circle Game”—lovely, but not the best work from Joni Mitchell’s folky days—was for a time so widely known and respected that it became a teaching song, drilled into the consciousness of 1970s children left to the mercy of guitar-strumming parents, teachers, and hippie camp counselors. Meanwhile, the more lyrically dense “My Back Pages” has always been considered classic Bob Dylan poetry on the theme growing up (by staying young), and Pete Townshend’s “My Generation” is a staple of rock ‘n’ roll defiance, the definitive song of inter-generational aggression.

It would be crazy to say that “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” is better than any of these songs. It’s not. The concept had depth, but the lyrics were not sophisticated. Nor was the delivery. The lead voices—both Mike and Brian—sound immature. “My Generation”—likewise sung in the voice of a teenager—would surely have flattered the Who’s young male fans, making them feel tough and rebellious. If anything, “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” would have done the opposite. The tag—when I grow up / to be / a man, with Brian singing way up high—is actively uncool. Who sounds like that? What teenage boy of any era would want to sound like that, or be flattered by the idea that this is what he sounds like? In a nutshell, the awkward, pubescent character of “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” is likely the main reason the song never made it with the rock ‘n’ roll crowd or even the Beach Boys’ own fans.

However, right or wrong, Brian Wilson believed that “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” told the truth about what kids are really like on the inside. It could also have reflected how he himself was feeling. Accordingly, “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” sounds the way it does. It conveys no penetrating insight on the circle of life; no declaratory statement about growing older. Grown-ups might have that kind wisdom to share, but kids don’t, because they don’t have the perspective. And because kids don’t know about that stuff, the song doesn’t know either. The listener isn’t going to learn anything from “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” or feel more grown up or adult for having heard it.

Is the song therefore “dumb,” lame,” or “embarrassing,” or does it only make you feel a little embarrassed to listen to it? These are two different questions.

Feel is the key. The songs by Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, John Lennon, et al. convey their messages about growing-up through lyrics. With Brian Wilson, it’s a musical feeling, more than an intellectual or conceptual insight that is captured. (With Brian, the feeling is the insight.) With the help of the Beach Boys on the vocals and Mike Love on the lyrics, Brian puts you inside the feelings of a certain kind of 14-, 15- or 16-year-old boy. If “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” is dumb or lame—unworthy to be classified among some of these other songs of the 1960s—it’s because it’s too intimate and too real.

In “The Circle Game,” Joni Mitchell sang about the “seasons going ‘round and ‘round” and how we’re all “captive on the carousel of time.” On “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys eschewed lyrical elegance and just stuck the listener right on the carousel itself—during the bridge and especially the fade out, when the Beach Boys count off the years as they quickly expire in succession. Both songs say that time is too powerful, and there’s nothing you can do about it. Joni Mitchell tells you something about the seasons and the years, and it certainly works—the chorus of “The Circle Game” is truthful. Meanwhile, Brian communicates in a different way, making the listener feel the message through instrumental and vocal arrangement, which is then buttressed by a good-enough (not great) lyric.

Brian’s approach is an unintellectual, but very musical and artful method of pop songwriting, appearing time and time again throughout his Beach Boys and solo discography. It was intentional, too. Even at that relatively early stage of his career during which he made “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man),” Brian had awareness of what he was doing as a writer and record producer. In fall 1964 he said:

My ideas for the [Beach Boys] are to combine music that strikes a deep emotional response among listeners and still maintains a somewhat untrained and teen-age sound.7

If Brian Wilson’s life, career, and music can be said to be important, then this is one of the most important statements he ever made in the press. It explains an awful lot—why Brian and the Beach Boys succeeded, and also why so much of Brian’s music was (and perhaps remains) misunderstood or misinterpreted.

However, did Brian know why he was inclined to write songs and make records this way? That is an entirely different subject.

For my purposes, “rock culture” or “rock ‘n’ roll culture” is shorthand for the mainstreaming (and the eventual, and ongoing, corporatization) of the Sixties counterculture.

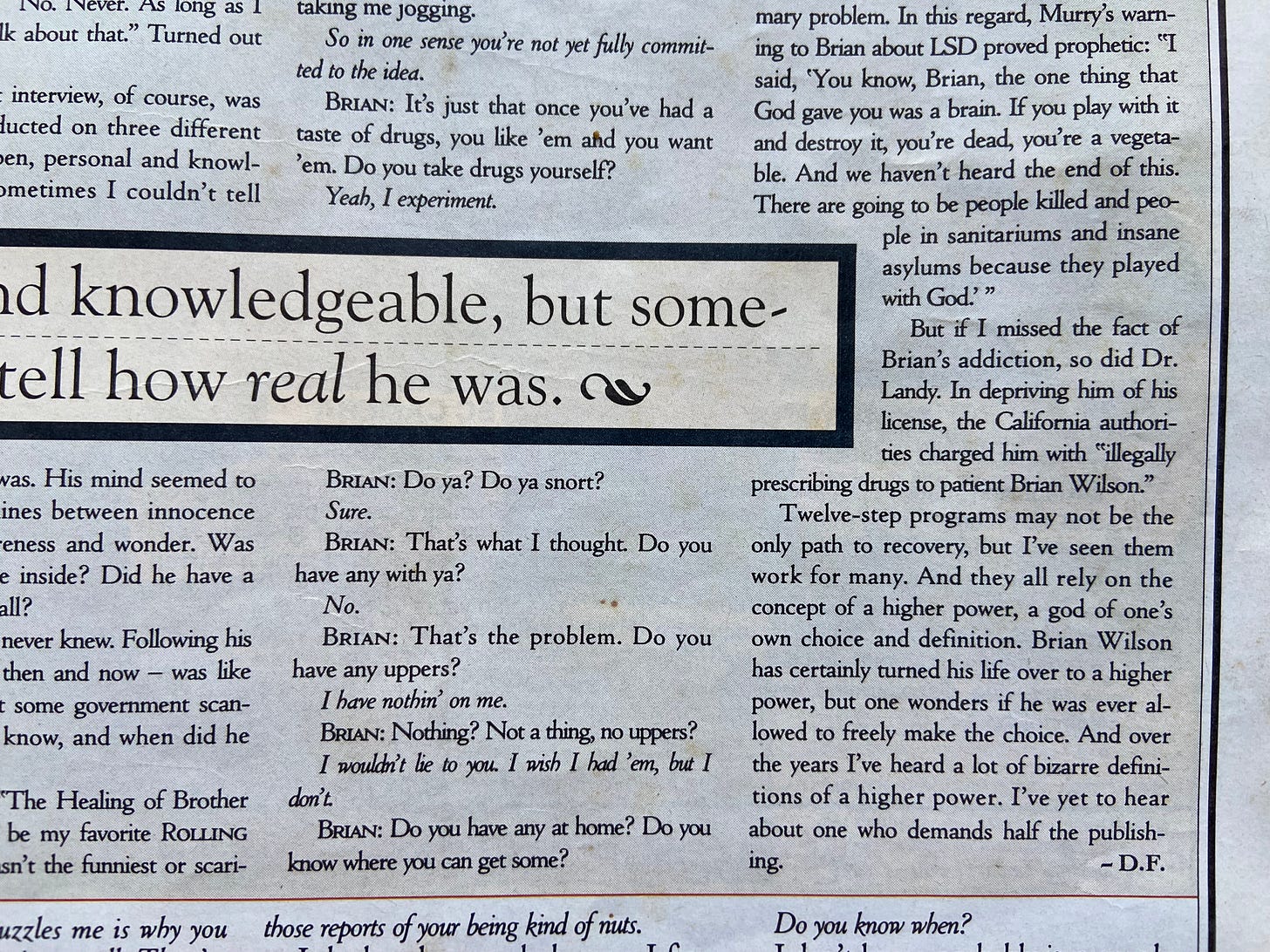

In Rolling Stone’s defense, the magazine duly conducted an interview of Brian and the entire Beach Boys band-family in 1976. However, as Ben Fong-Torres says in his introduction to the 1981 book, Rolling Stone prided itself on interviews with “probing questions” and “thoughtful responses” that necessitated a relaxed, conversational back-and-forth between artist and journalist. Even at a time when the Beach Boys were riding high as a concert attraction, the 1976 Rolling Stone piece revealed, at best, a shambolic family organization whose best days were behind it, and with a very troubled person at its center. (This is the notorious interview in which Brian asks interviewer David Felton if he has any drugs to share.) Addressing the various omissions from the 1981 interview collection, Fong-Torres explained that some artists were better suited for a “personality profile” instead of a Q & A. He then acknowledged the absence of “some important people” from the collection—namely Elvis Presley, Jimi Hendrix, and Janis Joplin. Excerpts from Brian’s 1976 Q & A were included in another interview collection gathered for the October 15, 1992 issue of Rolling Stone, along with updated commentary from Felton:

This was noted in Claude Hall’s “Collegiate Circuit” column in the April 23, 1966 issue of Billboard.

Among other things, the commercial disparity between “Do It Again” and Friends reflects Brian Wilson’s failure to achieve one of his mid-1960s goals: to transform the Beach Boys from a singles band to an album band.

In the recent Beach Boys documentary film (Disney+, 2024), Al Jardine candidly states that the Beach Boys were “singers” while the Beatles (and therefore virtually every notable band that followed) were “players.” The Beach Boys could (and did) play their instruments, but like their true predecessors the Four Freshmen, they were conceived as a vocal group, and this was the mode through which they established their musical identity. The four- (or three-, or five-) piece bands couldn’t do what the Beach Boys did, but they were leaner and more flexible. Meanwhile, as individuals, the Beach Boys lacked that post-Dylan singer-songwriter quality; there’s little evidence that Brian Wilson was ever inclined to sit down at the piano and just put a song over on the strength of the concept, the music, the lyric, the delivery, and the attitude. (Beach Boys Party! (1965) is not a serious album, but there are moments on Wild Honey (1967) when the Beach Boys seem to be doing a group-version of stripped-down music, just piano and harmony vocals.) Brian was of course a singer-songwriter insofar as he wrote songs and then sang them. However, he went about it in a different way, using the studio environment as a songwriting tool; “performing” his songs by releasing records. Brian was not really a singer-songwriter in the more common sense of the term.

The life cycle of “Sugar Mountain” is interesting. Having first been written in 1964 or ‘65, it took about 13 or 14 years for it to become a “hit” (fan favorite) in the late 1970s. Because “Sugar Mountain” first achieved widespread notoriety when Neil Young was a well-established artist in his thirties, the youthful uncertainty and vulnerability with which it was originally written became obscured. Not so with “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” which in its definitive, August ‘64 version is very much tied to the emotional context in which it was conceived and written.

The quote comes from the October 1964 issue of Capitol Records’ promotional magazine The Teen Set.