The previous post, Part 7, tried to get inside the unspoken psychological relationship between Brian Wilson and his father Murry. The relationship was strong, the bond was tight, but the whole thing was founded on violence and lack of trust. As such, the father-son relationship was inherently one of conflict; the only question was how the conflict would manifest itself as time passed and family circumstances evolved. Once the Beach Boys got going, what issues might Brian and Murry battle over? Could those conflicts ever be resolved, and if so, how?

Here, Part 8 introduces a new point of dispute into the story: the matter of the “the outsider” in Beach Boys and Wilson family politics. Those already familiar with Beach Boys history are aware of the recurring theme of the problematic outsider and the band-family’s frustration with—and ultimately, opposition to—Brian’s habit of looking beyond the family for sympathetic musical collaborators. The following post introduces Gary Usher, who in 1962 became the first significant outsider to write songs with Brian.

Part 8:

One day early in 1962, the Beach Boys were rehearsing at the Wilson home in Hawthorne. The music could be heard around the neighborhood and caught the ear of Gary Usher, an aspiring singer and songwriter who happened to be visiting relatives who were the Wilsons’ neighbors.1 Usher, an aspiring musician-songwriter who worked days as a bank teller, had been trying to establish a foothold in the L.A. pop scene and had already recorded a couple of go-nowhere independent singles under his own name. He dropped by the Wilson home and introduced himself. Within hours he and Brian had written a spare, moving ballad called “Lonely Sea.”

This collaboration speaks for itself. It says that Brian was, at the very least, receptive to writing with somebody outside the not-fully-formed Beach Boys. And that he believed it was his prerogative. It may very well have his preference too. Usher and Brian first met in January 1962, the same month Brian and Mike Love penned “Surfin’ Safari” (the natural follow-up to “Surfin’”), which would (after its eventual recording and release) become a staple of early’ 60s rock ‘n’ roll. In hindsight, it appears that once he connected with Usher, Brian was faced with a choice of collaborators, and that through his actions, he expressed a preference for the outsider: Brian and Gary would soon write a number of songs together and begin discussing the idea of starting their own company to publish them. Usher, who was 23 to Brian’s 19, had seen enough of the business to know that if a songwriter really wanted to reap the financial benefit of his work, it was in the publishing. That’s where the money was.2

Wilson-Usher was a commercial songwriting team that wanted to write hits. Today, rock ‘n’ roll music is enjoyed by very old people. But in 1962, making commercial rock ‘n’ roll—to the extent rock ‘n’ roll was a viable genre—meant doing something that adolescents (if not outright children) would like. The surfing theme had worked well for the Beach Boys their first time out but for some reason Brian and Gary stayed off the beach entirely. Their list of songs suggests that they got together and spitballed cute, frivolous themes: “Cuckoo Clock,” “Heads You Win, Tails I Lose,” “County Fair,” “Ten Little Indians,” and “Chug-A-Lug,” a song about drinking lots of root beer.

These tunes would eventually appear on the Beach Boys’ first album, Surfin’ Safari, later that year. Judged by later pop standards (or even those of the era) the songs are a bit empty, but as Beach Boy David Marks—a child himself when he played rhythm guitar on these recordings—once noted, they were honest and sincere. This is what Brian wanted to do with the Beach Boys in 1962. He was 19 or 20 years old and had only just begun writing in earnest. At this point, the main pre-conceived expectation regarding subject matter was just that the songs be kid-friendly; Brian wouldn’t have felt too pressed to write exclusively about surfing and the beach. (That would occur the following year). There is a naïve, youthful humor in the early Wilson-Usher songs—even a little teenage cleverness here and there—but not much else.

Anyway, Brian and Gary did better when they stopped pandering and looked to their own lives for material. Usher’s interest in fast cars yielded the Beach Boys’ spare, garage-rock track “409,” while Brian’s emotions would become the source material for the classic “In My Room.” This song (which was probably written at the end of 1962 and would not appear on record until the latter portion of 1963) was unusual—a pop ballad that was wholly about the solitary, inner life, without reference to romance or boy-girl relationships.3 However, it’s doubtful anyone picked up on the song’s uniqueness at the time, or was sensitive to the unidentified source of the “fears” referenced in the lyrics.

“In My Room” is a lineal ancestor of Brian’s celebrated Pet Sounds album, and it was written the same way: Brian discusses personal issues with an outside collaborator who is neither a family member nor a Beach Boy. Brian then writes the music, and the outsider helps by translating Brian’s intentions into lyrics. Subsequent Beach Boys history shows that Brian would for a time be able to collaborate with cousin Mike Love on external, prefabricated concepts, sales pitches, teen-lifestyle songs, maybe even a boy-girl ballad here and there. That is, Brian and Mike could (and did) collaborate successfully as craftsmen and businessmen. But if Brian ever wanted to do work like “In My Room,” he would have to write the words himself or locate an outsider.

More than 25 years later, in his autobiography Wouldn’t It Be Nice: My Story (a less-than-100%-reliable work stained by Brian’s psychological merger with his Murryesque psychotherapist Eugene Landy), Brian remembered that he and Usher

told things to each other that we wouldn’t share with our families or our girlfriends, secrets we wouldn’t discuss with anyone else. We understood each other without having to explain. Both of us felt an urgent, panicky need to prove ourselves, believing that the acclaim of success would heal our wounds or at least make us forget them.

As of the time that book was published in 1991, Brian may have been motivated to idealize his past with Usher, contrasting their youthful bond with what he perceived to be his mistreatment and exploitation at the hands of his own family. But even taking that into account, the recollection is essentially accurate. What Brian described was the kind of relationship that could produce an “In My Room.” There was a baseline trust in the working relationship Brian had with Gary Usher. “In My Room” is proof of it. Brian would never share that kind of creative trust with any member of his family.

When “In My Room” was written, Brian could very well have still been living (and/or composing music) in his parents’ house. It will likely never be known what, exactly, Brian shared with Usher (who died in 1990) about his life. Usher could certainly sense the obvious—that Murry was an ill-tempered blowhard who had a messed-up relationship with his son; that he viewed Usher as an interloper in a family business. But Usher may not have been aware that Murry was not just another strict father on a power trip. Murry was a deranged man whose status as “father” had given him cover to commit atrocities against his children—things that had taken place in the very same house in which Brian and Gary had written (at least some of) their songs.

Usher is unlikely to have understood that Murry was threatened not just by him, but even more so by Brian. Murry was, at best, ambivalent about the idea of Brian having a career in music—especially as a songwriter. Given that Brian had nevertheless found his way into the business and was now developing a fledgling profile as a writer, it had become imperative for Murry to constrain Brian, reducing him to the lowly status of implement to be owned, shaped, and controlled for Murry’s own purposes. Usher’s meddling presence could only obstruct Murry’s efforts in this regard. From Murry’s perspective, the Brian Wilson-Gary Usher partnership existed between a disloyal, disobedient traitor and a thieving trespasser.

When the purposefully cruel treatment of children occurs behind the veneer of a healthy, intact nuclear family, the perpetrators will ensure that the family nevertheless remains close and tightly-knit. (In such cases, it is really the abuse itself that holds the family together. If the abuse truly comes to an end, the family is no more.) When the recipients of such treatment are still kids, the maintenance of strong intra-family ties ensures that the torment can continue without discovery by outsiders. Once the children are physically grown (as Brian was in 1962), the game shifts, with the purpose not only to preserve the status quo, but to ensure that the adult child never comes to understand what was (and continues to be) done to him.

Guilt, denial, and abject fear are commonly used to keep battered kids close to home, but there is also the child’s natural and otherwise healthy inclination toward family loyalty and pride. To this end, abusers will commonly instill distrust of the non-family member or outsider. The result is that the insularity of the violent or oppressive family system—as differentiated from the sufficiently healthy family unit that is the foundation of any civil society—mirrors that of death cults, bloodthirsty religious sects, chauvinistic racial-identity groups and oppressive, paranoid nation-states.

In Murry’s own words, Gary Usher was “an evil influence on our family.” And Murry was right—if “family” is code for the status quo whereby Murry reigned autocratically, free to abuse and exploit his sons (especially Brian) in perpetuity. In other words, when Murry characterized Usher as “evil,” he was acknowledging (unintentionally, of course) that Gary had been a good and positive influence on Brian Wilson the young man. And for Murry, that was intolerable.4

As had been the case months earlier when Brian and the boys surreptitiously formed the Beach Boys behind Murry’s back, Murry could not avail himself of his preferred methods of violent suppression. Notwithstanding Brian’s non-violent nature, it would have been too dangerous for Murry to assault him the way he used to. (As a chronic child-batterer, Murry was a physical coward, and Brian was now about 20 years old and stood 6’ 3.”) So Brian was now writing and bonding with the outsider Gary Usher, and Murry couldn’t put a stop to it as easily as he would have liked.

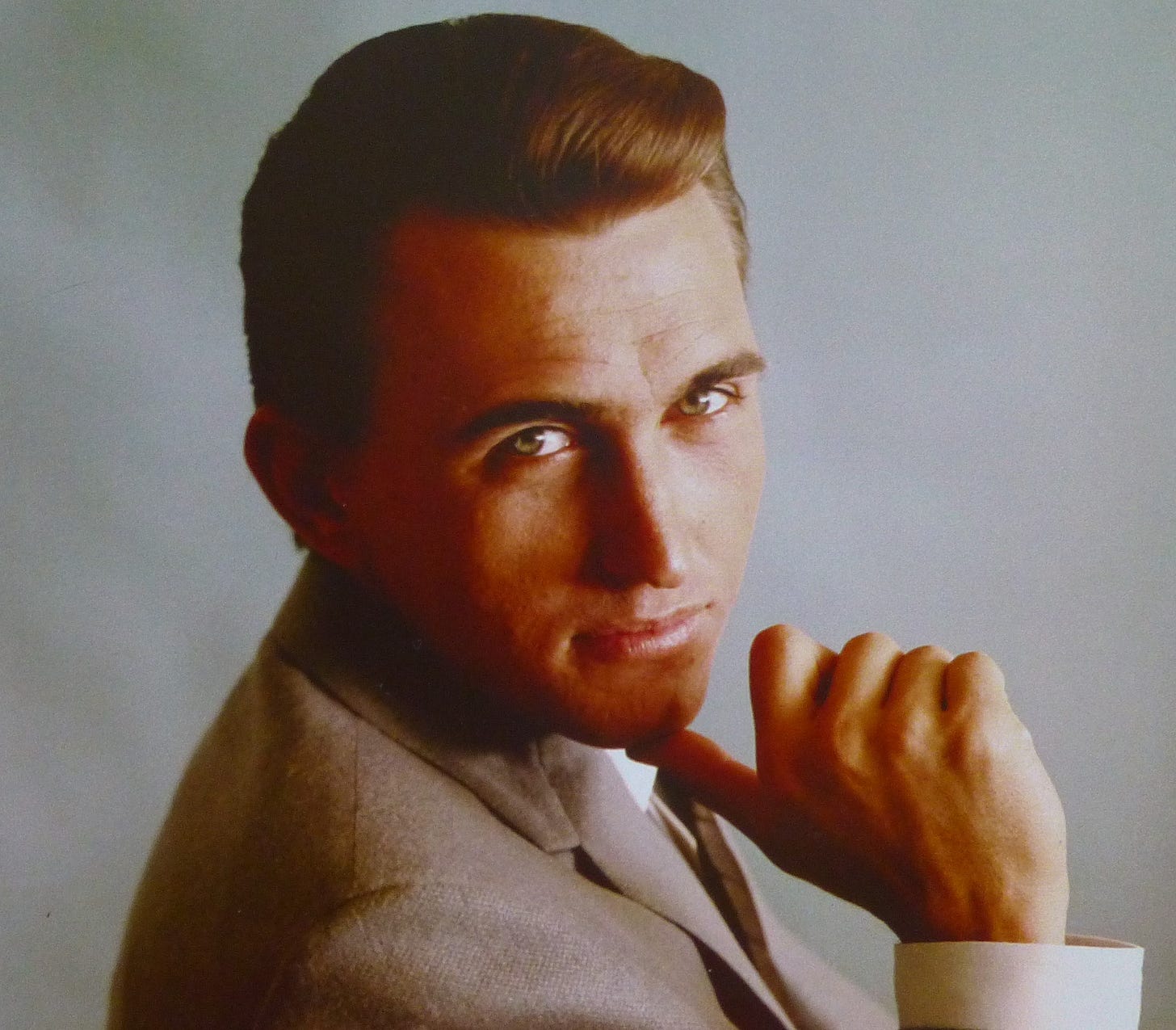

Given his warped subjectivity, Murry had no choice but to castigate Brian, badmouth Gary, and denigrate their collaboration. Usher was an older male who wrote songs with Brian while Murry did not. Usher had released his own singles, attained some business knowledge, and whatever contacts he maintained existed free and clear of Murry’s influence. He was handsome, confident, and ambitious—par for the course in Hollywood—and the kind of guy who would, of his own volition, knock on a stranger’s door and network. Usher had never been beaten, humiliated, or terrified by Murry during childhood, and Murry was not married to Usher’s mother. It was therefore easier for Usher, as outsider, to see Murry for what he really was.

Usher indeed made no secret of his dislike of Murry and his songs, even foolishly criticizing them while a guest in Murry’s home. According to biographer Steven Gaines (who interviewed Usher, perhaps multiple times), during a writing session Murry simply kicked Usher out of the house. As he walked back down the street to where his relatives lived, Usher could hear Murry screaming at Brian. Obviously, Gary Usher’s days as an adjunct Beach Boy were numbered.

The narrative continues in A History of Brian Wilson, Part 9—click here to keep reading

Selected References for Part 8

Gaines, Steven. Heroes and Villains: The True Story of the Beach Boys. New York: Signet/New American Library, 1986.

Herman, Judith. Trauma and Recovery. New York: Basic Books, 1997.

Lambert, Philip. Inside The Music of Brian Wilson: The Songs, Sounds and Influences of the Beach Boys' Founding Genius. New York: Continuum International, 2007.

Leaf, David. The Beach Boys and the California Myth. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1978.

Love, Mike, with James S. Hirsch. Good Vibrations: My Life as a Beach Boy. New York: Penguin/Blue Rider, 2016.

McParland, Stephen J. The Wilson Project. Editions Berlot, 2012.

Murphy, James B. Becoming the Beach Boys 1961-1963. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2015.

Rusten, Ian, and Jon Stebbins. The Beach Boys in Concert: The Ultimate History of America's Band on Tour and on Stage. Milwaukee: Backbeat Books, 2013.

Sharp, Ken. “Brian Wilson: God’s Messenger.” American Songwriter, January 2, 2009. At: web.archive.org/web/20111225045200/http:/www.americansongwriter.com/2009/01/brian-wilson-gods-messenger/ (last accessed November 17, 2023)

Stebbins, Jon. The Lost Beach Boy. London: Virgin Books, 2007.

Storr, Anthony. Feet of Clay: Saints, Sinners, and Madmen: A Study of Gurus. New York: The Free Press, 1996.

Wilson, Brian, with Todd Gold. Wouldn't It Be Nice: My Own Story. New York: HarperCollins, 1991.

It is possible that Usher had already heard the Beach Boys on the radio with “Surfin’” and knew very well who was making all the noise. Brian Wilson said as much in his 1991 autobiography, Wouldn’t It Be Nice: My Own Story.

By choosing to work creatively with Usher rather than the family exclusively, Brian was arguably expressing his preference for a specific type of career in music: to be a songwriter-producer (and publisher) rather than a performer or pop star. He was also demonstrating a native instinct toward personal health, for by putting space between himself and the barely-formed Beach Boys, he would be putting space between himself and his father and what his father represented. But personal health isn’t the same as financial or career well-being; subsequent events would show that if Brian wanted to get a foothold in the business at this early stage, the best bet was to stick with the family, with Mike, and the surfing-concept that had earned Brian his first local hit. This Brian would do, but not before trying to wedge Gary Usher into the Beach Boys family business, as discussed in this and subsequent posts.

Unlike “409,” “In My Room” was likely written at the tail-end of the Usher-Wilson partnership in late 1962, maybe even early 1963. (?) With all due respect to Brian and Gary, the outstanding “In My Room” would probably not have been conceived were it not for Carole King’s and Gerry Goffin’s meaningful and thematically similar “Up On the Roof” for the Drifters in 1962. (Though unlike Wilson and Usher, Goffin-King still allotted “room enough for two” on the roof. The singer in “In My Room” is alone.) “Up On the Roof” only first appeared on the singles chart in December 1962, soon after the Beach Boys put out Wilson-Usher’s “Ten Little Indians.” Brian and Gary would not only have admired “Up on the Roof” on its merits, but also noticed how it climbed the charts while their own “Ten Little Indians” stiffed. The writing of “In My Room” might therefore be taken as evidence that Brian and Gary had absorbed a lesson about maturity in pop songwriting. For a number of reasons, it would be a while before Brian would return to the “In My Room” mode of songwriting in full force and create his greatest work.

Usher would prove to be a positive influence on Brian Wilson the middle-aged man, too. During the 1980s, Usher re-entered Brian’s chaotic life and would play an important role in the effort to wrest Brian from the control of Eugene Landy (aka Murry Wilson with a Ph.D.) See Stephen J. McParland’s The Wilson Project. For a less charitable view of Usher and his interference in the Wilson-Landy relationship, see Brian’s own Wouldn’t It Be Nice: My Own Story. However, its relevant passages were likely colored by Landy’s influence over Brian, perhaps being the product of Landy’s own editorial hand. Given the then-current legal wrangling, the criticism of Usher in the 1991 book is unconvincing. These matters are otherwise beyond the scope of this historical narrative.