Among other subjects, the last post, Part 3 of A History of Brian Wilson, revisited Brian’s exposure to music during childhood and adolescence. It left off with Brian’s special affinity for the Four Freshmen, a male vocal group of the 1950s whose stylistic trademark was a stacked, multi-part vocal harmony.

To continue:

It was through his exposure to the Four Freshmen that Brian really got hip to the craft of vocal arranging. He experimented, creating his own arrangements of other people’s songs and recording them on a small reel-to-reel rig that his father had bought for him. Brian knew all the parts, and would apportion them among his family—Mom, Dad, Carl, himself—with the end result being an expression of familial harmony put to tape. Even if wayward Dennis was less involved in Brian’s more formal efforts, he too absorbed music, picking up some piano and singing with his brothers in their shared bedroom—Brian leading a three-part version of the ‘50s tune “Ivory Tower”—and in the backseat of the family car. Brian was not just having fun here. Consciously or unconsciously, he was applying his skill toward the creation of a genuine family unity when otherwise, there would have been none.

A few miles north, in the Baldwin Hills section of Los Angeles, Mike Love and his siblings were also being raised in a musical household. So when Murry and his sister Emily Glee would get their families together on special occasions, music was happening. There was more playing, more singing, and more harmony.

And more ugliness too. At one gathering, after Dennis pilfered some booze, the extended family watched as Murry picked him up and threw him against a wall. At another, during which a pre-pubescent Brian sang a song that his young cousin Mike had written, Murry hijacked the tune, rewrote the lyrics, then directed Brian to sing the revised version.

This incident provides an early glimpse into Murry Wilson’s state of mind with respect to Brian and his musical prospects. It points to the degree to which Murry jealously guarded his proprietary interest in Brian’s talent: if Brian was ever to express himself in music—even if only as a performer, and as a child in the innocuous setting of a family gathering—Murry must always be present and in control, dictating the terms and conditions. The idea that Brian could become not just a singer but an actual composer of music was likely inconceivable to Murry at this early stage, but that would prove to be an even bigger problem for him in later years. In the future, any of Brian’s non-Murry collaborators (barring those approved by Murry) would always be viewed with suspicion, if not outright hostility.

Murry’s usurpation of Mike’s song is an early example too of the chronic pattern whereby Murry attempts to appropriate (or take credit for, or steal outright) the work of Brian and the Beach Boys and claim it as his own property. (In this he would ultimately succeed.) In later years the Beach Boys would be plagued by a dysfunctional strain that manifested itself in, among other things, battles between Brian Wilson, Mike Love and Murry Wilson over songwriting credits and publishing. It seems those particular storm clouds were gathering as far back as the early 1950s.

Back in those days, however, before things turned sour for Brian Wilson and Mike Love, it was more or less good times. The oldest of the pack of Wilson cousins (and therefore naturally positioned as leaders), Brian and Mike shared an interest in popular music. They would listen to, and learn from, the radio during family get-togethers, sleepovers, and later, in their cars. Mike wasn’t a Four Freshmen acolyte like Brian, but they shared common ground in other harmony styles like doo-wop and the two-part singing of the Everly Brothers. There was also Atlantic Records-style rhythm & blues, with which Mike is said to have developed a familiarity while a student at Dorsey High School in Central Los Angeles.

Meanwhile, Brian was down at Hawthorne High, leading what would have been an outwardly normal existence for a middle-class Southern California lad of the 1950s. Brian was neither an outcast, nor bigshot on campus, nor an artsy, junior-beatnik. His grades were fine and he didn’t cause trouble. Once he turned 16 and got his driver’s license, his parents got him a clunky hand-me-down car to get around in. Brian’s circle of friends and acquaintances were guys who, like himself, played sports and enjoyed singing. (Brian found a way to do both at once, singing to himself while playing centerfield.) The girls were pretty and had names like Carole, Pat and Glenda. These were white kids with Midwestern ancestry growing up during the Cold War, against a backdrop of regional industry: aeronautics, national defense, fossil fuel extraction and tire manufacture, with the latter two directly linked to the car culture (and smog) in which the kids were being raised. Family life was built around the affordable single-family home—a physical, street-level symbol of America’s respect for the individual. Then as now, the home was a freestanding setting in which parents could raise their girls and boys up right, and do so in all the privacy afforded by law.

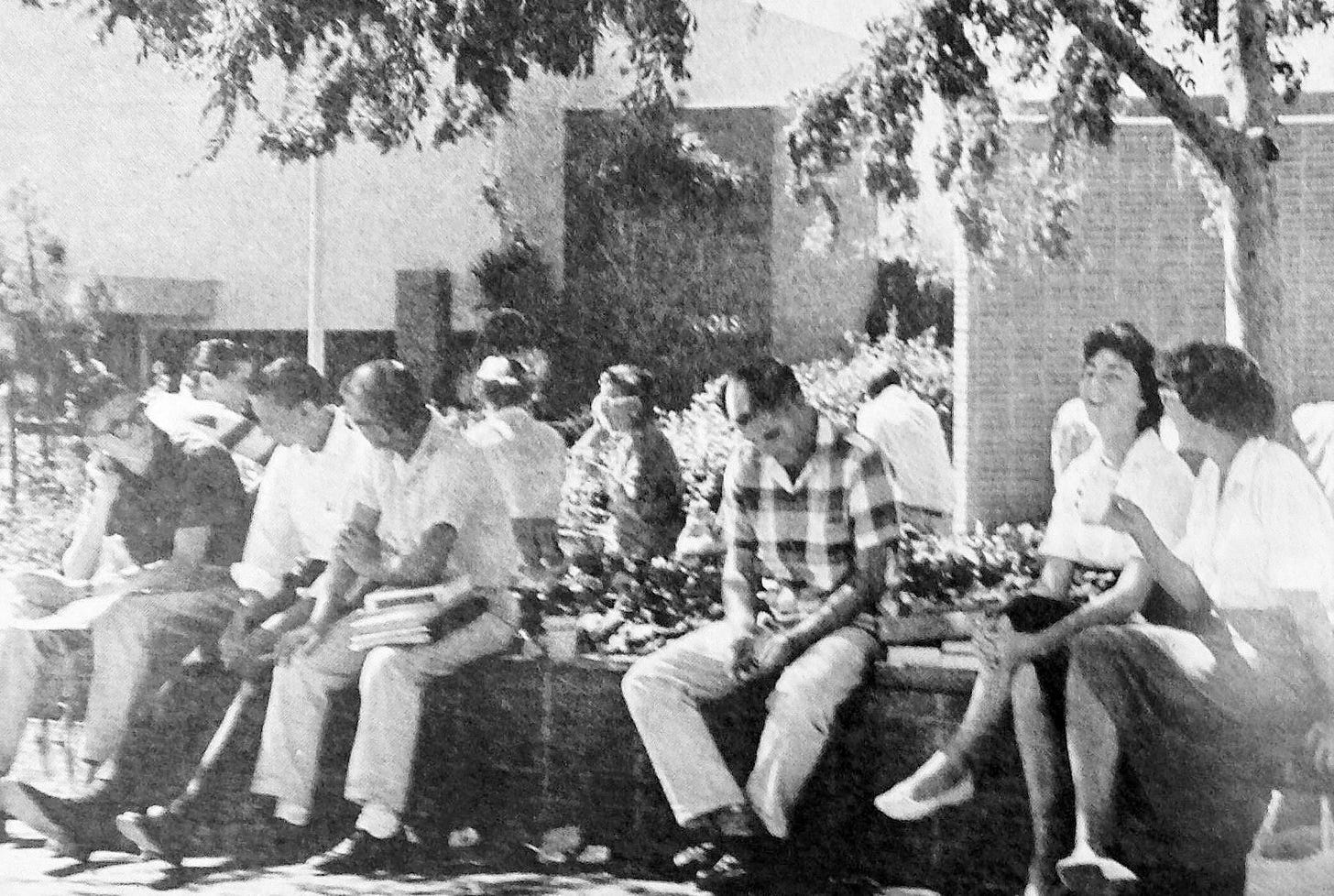

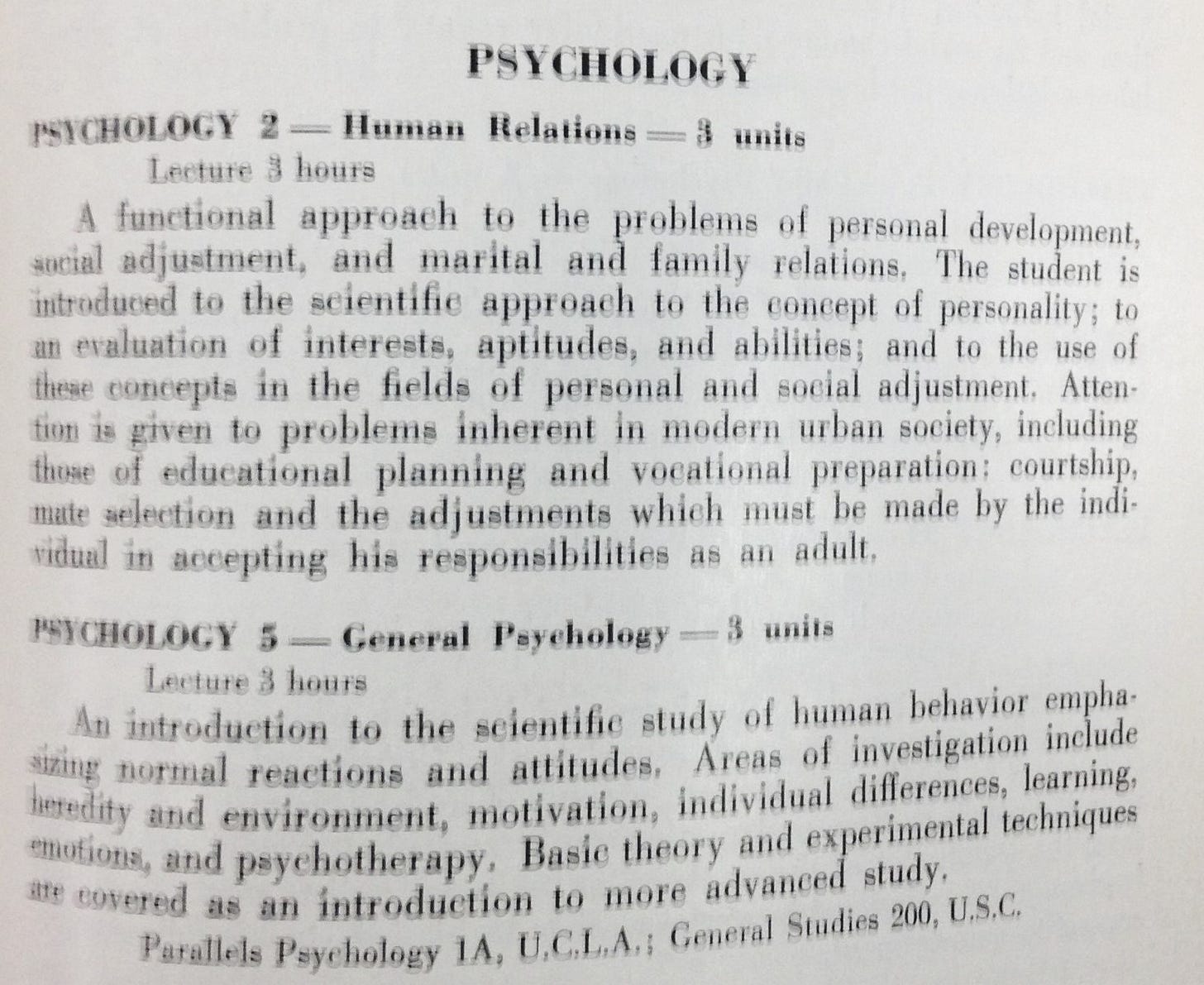

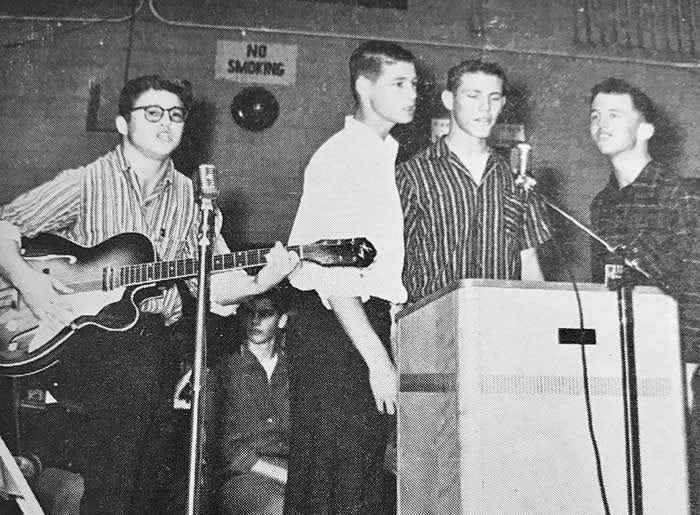

As of his senior year at Hawthorne High, Brian was harmonizing with friends in group format on stage at school assemblies, and had already come to sense that in some way, music would be his life’s work. He graduated in the spring of 1960 and in the fall enrolled at El Camino College, the two-year school serving the South Bay communities. Brian took classes in music and psychology—subjects that would merge later in life to legendary effect. El Camino’s music department offered four courses in “Music Listening and Appreciation.” Brian took at least one of these, finding it stuffy and unduly prejudiced against the pop music he loved. Beyond that, it’s unknown what classes Brian took, but he would have been able to choose from courses like “Vocal Ensembles,” “Creative Musicianship” and “Fundamentals of Counterpoint.”

Meanwhile, El Camino’s handful of psych classes, including “Child Psychology” and “Human Relations,” offered a formal point of entry to subjects like motivation, nature vs. nurture, “the psychological development of the child” and “the problems of personal development, social adjustment, and marital and family relations.” El Camino was conveniently located a few miles down the road from the Wilson home in which Brian continued to live with his parents, Dennis and Carl.

As of the time Brian was in college, the rock ‘n’ roll scene was in a state of awkward transition, not yet the mega-business it would later become. The first wave of rock ‘n’ roll—a form of popular music that was birthed in the 1950s with greats like Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly—had receded, and there was no surplus of outstanding rock ‘n’ roll being made. Los Angeles was home to labels which recorded West Coast-style jazz (which appealed to young college-types), and of course, big-time Capitol Records in Hollywood, whose roster included popular, jazz-rooted singers like Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra and the Four Freshmen.

Rock ‘n’ roll was understood to be kids’ music—simple, crude and dumb—and at a label like Capitol there was scarcely any personnel dedicated to it. In Los Angeles, the genre was instead the territory of small independent firms that had proliferated after the Second World War and lay scattered around the Hollywood flats. Their business model was capitalist but not corporate: various sources present an image of small operations run by chainsmoking, brylcreemed men who “lived above the store,” and ran volume businesses on the cheap. They signed hungry, naïve young talent to lopsided recording and publishing contracts. The performers recorded a song or two, and a 45-rpm single got pressed and distributed locally. Maybe something would stick.

Within this music ecosystem, the local high schools could serve as a natural talent pool. With some initiative, musical kids from schools like Fairfax, Uni, Hollywood, Pali and Westchester could leverage their geographical proximity to Hollywood and whatever personal connections they had and end up with an audition, maybe even a single.

Alan Jardine, a friendly acquaintance of Brian’s from Hawthorne High, fit this profile. Jardine’s thing wasn’t the Four Freshmen sound, or rock ‘n’ roll or R&B, but he was still into vocal harmony, as expressed via the “folk trio” format. This style, exemplified by the then-very popular Kingston Trio, was a polished folk-pop hybrid built around acoustic instruments, strummy arrangements, and a polite vocal blend. Jardine wanted to record his folk trio professionally, and needed a way in. One potential lead was the family of his former high school classmate Brian Wilson. Al Jardine knew that Brian’s dad was a songwriter who had some contacts up in Hollywood.

As far as the Wilson family was concerned, Murry wasn’t just a songwriter. He was the songwriter. Although Brian had developed into an excellent singer with a great ear and uncanny talent for arranging vocals, he was not a writer. The pulling of melodies from thin air was Murry’s province, and everybody knew it. Back in the early 1950s when his tunes first began to sell, Murry’s sister Emily Glee even threw a party, the point of which was to honor Murry and his songs. (She hired professional musicians to play Murry’s music live.) Murry’s writing never quite took off; it would remain an avocation. Still, this one-eyed guy from nowhere had legitimately achieved something, and he had tangible proof in the form of commercial vinyl with his name on the label as credited writer.

Murry also had the showbiz contacts—not with the big labels, but the little guys—namely the husband-and-wife team of Hite and Dorinda Morgan, who ran the tiny company that had published (i.e., owned) Murry’s songs since the early ‘50s. The Morgans’ company, Guild Music, was literally a mom & pop outfit. It included a small studio for demo recordings that the Morgans would own and then pitch to the labels.

When he decided to contact the Wilson family for help, Al Jardine set in motion a very curious sequence of events.

To continue, go to A History of Brian Wilson, Part 5

Selected References for Part 4

Gaines, Steven. Heroes and Villains: The True Story of the Beach Boys. New York: Signet/New American Library, 1986.

Hoskyns, Barney. Waiting for the Sun: Strange Days, Weird Scenes and the Sound of Los Angeles. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1996.

Leaf, Earl. “The Beach Boys.” The Teen Set, Vol. 1, October 1964.

Love, Mike, with James S. Hirsch. Good Vibrations: My Life as a Beach Boy. New York: Penguin/Blue Rider, 2016.

McParland, Stephen J. Murry: The Many Moods of a Beach Boy Dad. CMusic Books, 2022.

Murphy, James B. Becoming the Beach Boys 1961-1963. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2015.

Nolan, Tom. "The Beach Boys: Tales of Hawthorne" Rolling Stone, November 11, 1971. As republished in Kingsley Abbott, ed. Back to the Beach: A Brian Wilson and The Beach Boys Reader. London: Helter Skelter Publishing, 1999.

Selvin, Joel. Hollywood Eden: Electric Guitars, Fast Cars, and the Myth of the California Paradise. Toronto: House of Anansi, 2021.

Shaw, Greg. “The Instrumental Groups.” In Anthony DeCurtis, James Henke and Holly George-Warren, eds. The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll. New York: Random House, 1992.

Starr, Kevin. Golden Dreams: California in an Age of Abundance 1950-1963. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

White, Timothy. “Brian Wilson.” In Rock Lives: Profiles and Interviews. New York: Henry Holt, 1990.

Zanes, Warren. Revolutions in Sound: Warner Bros. Records The First Fifty Years. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2008.

Wilson, Brian, with Ben Greenman. I Am Brian Wilson. Boston: Da Capo Press, 2016.