The previous entry in this series, Part 2 of A History of Brian Wilson, offered an unpleasant but necessary introduction to life in the Wilson home during the 1940s and ‘50s. During those years, brothers Brian, Dennis, and Carl Wilson were raised in what would now be described euphemistically as a “dysfunctional” home environment.

This essay series takes the abuse to be a factual and historical reality. It happened. And with that foundational assumption, the History of Brian Wilson continues here, in Part 3:

At this point, a moment should be taken to remember that the Wilson boys were always separate individuals. They were brothers born to the same set of parents and raised in the same home, but were not simple replicas of one another. It is fair to speculate as to the distinct temperament each brother would have possessed—an unspecific, but recognizable, orientation toward emotion, sensation, the surrounding environment, and other people. As something distinct from the later formation of a full-fledged personality, a given temperament might have been noticeable in each brother as early as infancy or toddlerhood, with certain aspects remaining somewhat constant throughout their lives.

Human temperament is a somewhat mysterious field of inquiry, one that would seem far too complex, subjective, and metaphysical to be nailed down as an exact science. Still, temperament is commonly thought to be influenced by genetic predisposition. If that is true however, it must not be confused with the lazy, mechanical idea that “genetics” governed the lives of Brian Wilson and his brothers. It would be wrong, for example, to presume that Brian Wilson’s crippling experience with fear, anxiety and auditory-verbal hallucinations, or Dennis Wilson’s penchant for dangerous and self-destructive behavior, were preordained by their respective genetic coding. Nor for that matter should Murry Wilson’s status as a child-batterer be assumed to be a hereditary fait accompli, passed on to him through the blood by his own violent father.

The concept of temperament ought to serve only as a reminder that when children like Brian, Dennis and Carl Wilson are confronted with certain daily living circumstances—both the good and the bad—they may be naturally inclined to respond in different ways. As Brian Wilson has commented with respect to the brothers’ negative childhood experiences, “we all had to deal with it, though we all had our own ways of dealing with it.” Brian could have added that his parents then had their own ways of dealing with the ways their sons were dealing with the abuse. Things get complicated in the family.

The long and the short of it is that three brothers were isolated and unprotected in an extremely abusive home. Like all children who are violated by their caretakers, they had nowhere to go, nobody to turn to, and were left to their own devices to cope physically and psychologically over a period of many years. They would have to adapt to the situation they were born into.

Today, the layman is familiar with the fight-or-flight stress response, with which other options—“freeze” and “submit”—are now commonly grouped. Presumably influenced to some degree by their biological predisposition and/or temperament, Brian, Dennis and Carl adapted in textbook fashion. While the process of environmental adaptation implicates the complex neurochemistry of the central nervous system, each brother must be thought of as a human being—something more than a mere aggregation of cells, tissues and neural pathways reacting to external stimuli. Brian, Dennis and Carl adapted and survived not as “organisms” or “data points,” but as people. And they did so in the real world, not a controlled laboratory environment.

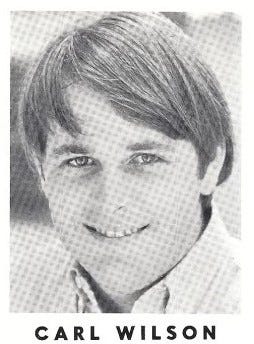

The process of survival led the brothers to develop distinct qualities as they grew; qualities that would solidify into established personalities and eventually shape the arc of the Beach Boy saga. Youngest child Carl was by all accounts balanced and stable, equipped with an ability to negotiate family strife. The supposed benefits for him included an exemption from Murry’s violent and perverse assaults, as well as a special closeness with his mother that his older brothers would never have.

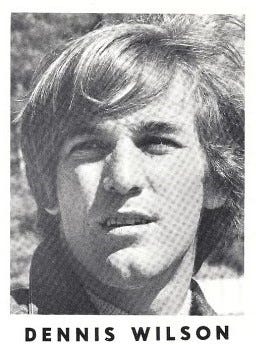

By contrast, Dennis was the prototypical rebellious, restless child. An image that has persisted over years of Beach Boys reportage is that of a very young Dennis sitting alone with his face pressed against the screen door at the front of the house as he looked out at the world beyond. As Dennis got older, his anxiousness found expression in delinquency, vandalism, fighting, and petty crime.

Oldest brother Brian possessed qualities that put him somewhere else entirely, distanced from both Dennis’s aggression and Carl’s equanimity. Whereas Dennis charged out into the world with reckless physicality, Brian went the opposite direction, turning inward to a place where intellect and emotion intersect. Yet unlike the temperate Carl, Brian for some reason remained unable to summon his father’s mercy or ingratiate himself with his mother. By all accounts, Brian was a nice, well-behaved boy who did well in school and athletics. Yet there was something about him that, like a magnet, pulled forth the old man’s rage and aggression. What was it about Brian? The vicious circle of violence between Murry and Dennis is clearer—Dennis responded to the abuse with physical rebellion and misbehavior, thereby gifting Murry with a pretext for still more violence. That father-son conflict was out in the open, visible not only to family members, but neighbors and casual observers. It may be theorized that between Murry and Brian, something else was going on, but under the surface.

Along with the abuse that continued unabated in the Wilson home, there was music. As it had been for earlier generations of the family, listening, singing and playing were activities that everybody engaged in at one time or another, and it’s probably true that music was the means through which Murry and Audree put their best feet forward. They were both music lovers who could play some piano, their mutual interest being one of the things that drew them to each other in the first place. While Audree was more naturally gifted with a musical ear, Murry was creatively inclined. He earned his living in hard industries like tire manufacture and machinery, but strove to become a professional songwriter. He picked out tunes on the piano, hustled and networked. As of the early 1950s, Murry was registering his songs with BMI and had at least a few of them recorded (to little success or notoriety) by performers on labels like RCA-Victor, Decca and L.A.-based Specialty Records.

Murry and Audree’s musicality was good news for Brian. It should be noted that Brian was neither a child prodigy nor was music rammed down his throat in the resentful, pedagogical mode of “tiger parenting.” There is no evidence that Brian’s affinity for music was anything other than genuine; an expression of his truest self. He had been drawn to music from a very early age, and his parents’ shared appreciation meant that he was left sufficiently free to pursue something that legitimately interested him.

Brian traces his involvement with music back to his earliest, pre-verbal childhood during which he responded—emotionally, internally—to a recording of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. He later took some formal lessons for a bit, sang in church and at school, and also picked up some piano from his parents and an uncle, in particular a boogie-woogie style that would influence his writing in the future. He listened to and absorbed the popular music of the ‘50s—stuff like vocally-oriented R&B and doo-wop groups, early rock ‘n’ roll, and the jazz and pop singing of Rosemary Clooney.

There was also The Four Freshmen, a group that sang vocal-harmony arrangements of well-known “standards” from the pre-R&B and rock era. The Freshmen were instrumentally capable—guitar, drums, horns—but didn’t come at these tunes like jazz instrumentalists or the typical solo jazz vocalist. The instrumentation was arranged to allow space for a carefully constructed, multi-part vocal harmony that added up to something more than the sum of its parts. In the 1960s, Brian Wilson referred to this as the Freshmen’s “groovy sectional sound.”

By the time he first heard the Four Freshmen in his early or mid-teens, Brian had been deaf in his right ear for at least several years. Brian’s hearing loss is a critical element of his story, not just because it meant he had only one ear with which to make his mark in music, but because, as he himself has stated now and again, the injury may have been the result of a ferocious blow to the head dealt by Murry at a time when Brian was too young to fully remember it. To date, Murry’s theft of Brian’s hearing is the only instance of abuse that has ever been reasonably called into question, for it is Brian himself who has vacillated, alternately attributing the damage to his father and a birth defect.

It might be assumed that Brian has been haunted by not knowing how, or why, he lost his hearing, but in 2016 he appeared to have settled the issue (or further muddied the waters) by tracing the injury to a new source: a villainous neighborhood youth named “Seymour” who clobbered Brian in the head with, oddly enough, a lead pipe. In any case, Brian had one healthy ear through which to absorb his musical influences.

During his teenage years, he spent countless hours with his Four Freshmen vinyl, a turntable and a piano (or organ), painstakingly and obsessively training his ear by breaking apart the Freshmen’s vocal arrangements part by part, note by note. For a significant chunk of Brian’s teen years this was basically what he did. He trained his voice by learning to sing each part on who knows how many Freshmen recordings, and eventually committed them to memory.

It is difficult to imagine the Four Freshmen’s careful treatment of old standards being very popular with teenage boys of the 1950s. Though the Freshmen were not as old-fashioned as they might appear from a more current perspective, they were whitebread, even by the relatively conservative standards of the day. Yet for Brian, there was something in the music that moved him. The Freshmen didn’t just provide him with listening pleasure, or even a D.I.Y. master-class in singing and vocal harmony. These records affected his very existence. Decades later, Brian looked back on that time and said that the Four Freshmen had given him “spiritual strength.” As he explained, “I purged all kinds of bullshit, and picked up the Freshmen.”

Brian of course needed spiritual strength because his spirit was under assault; the stakes were very high in the Wilson household. It makes sense that as he went about the process of negotiating a brutal, capriciously violent home life, Brian would want to go to a place where he could drill down into the interstices of the Freshmen recordings to learn where this strength came from. It came from music and, in the particular case of the Four Freshmen, vocal harmony. It is likely that these were the years of Brian’s life during which music began to merge with the process of brute survival—which is to say, with life itself.

To be continued in A History of Brian Wilson, Part 4

Selected References for Part 3

Bishop, Stephen. Songs in the Rough: Rock’s Greatest Songs in Rough-Draft Form. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

Ford, Julian D. “Neurobiological and Developmental Research: Clinical Implications.” In Christine A. Courtois and Julian D. Ford, eds. Treating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorders: Scientific Foundations and Therapeutic Models. New York: The Guilford Press, 2009.

Granata, Charles L. Wouldn’t It Be Nice: Brian Wilson and the Making of the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds. Chicago: A Cappella Books, 2003.

I Just Wasn't Made For These Times. Directed by Don Was. Palomar Pictures, 1995. DVD: Artisan Entertainment.

Jung, C.G. Psychological Types (Collected Works, Vol. 6). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1971.

Kagan, Jerome. Galen’s Prophecy: Temperament in Human Nature. New York: Basic Books, 1994.

Karr-Morse, Robin, and Meredith S. Wiley. Ghosts from the Nursery: Tracing the Roots of Violence. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2013.

Lawson, Christine Ann. Understanding the Borderline Mother. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004.

Maté, Gabor. In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2010.

Murphy, James B. Becoming the Beach Boys 1961-1963. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2015.

Pewter, Jim. “Brian Wilson Tells Jim Pewter All About the Early Days!” Bomp! Winter, 1976-77.

Wilson, Brian, with Ben Greenman. I Am Brian Wilson. Boston: Da Capo Press, 2016.

Winnicott, D.W. The Family and Individual Development. New York: Routledge, 1989.