Kansas-by-the-Sea

Part 1 of A History of Brian Wilson: the Wilson family arrives in Southern California in the 1920s.

This is the first in a series of posts tracing the stages of Brian Wilson’s life, from approximately 1942 (the year of his birth) through 1967. Relying heavily on the research of Timothy White, this post concerns the Wilson family’s migration from Kansas to Southern California, in the years before Brian’s birth.

In January 1988, at a hotel in New York City, the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame held ceremonies celebrating its third class of inductees. The previous two years had seen the induction of the legendary artists who had pioneered rock ‘n’ roll during the 1950s, and ‘88 was the year in which the music business would begin the process of recognizing the big names of the 1960s era. In addition to Bob Dylan and members of the Supremes, the Beatles, and the Drifters, the Beach Boys were present this night to receive the honor.

The ceremony was more or less intended as a private party for the music business and wasn’t televised. But the Hall of Fame filmed it, and has since made the Beach Boys’ induction—consisting of introductory remarks from Elton John and speeches from the Beach Boys themselves—available for viewing on the internet, where the moment remains fresh and lively.

With their respective speeches, Beach Boys Brian Wilson and Mike Love dutifully presented themselves as symbols of the schism within the Beach Boys which by that point had afflicted the group for more than 20 years. As of early 1988, Brian Wilson had not been creatively involved with the Beach Boys in any meaningful way for around 15 years (at least) and was struggling in life—deeply enmeshed with his ravenous psychotherapist, business partner, and life coach Eugene Landy. Nevertheless, the bespectacled, 45-year-old Brian managed to carry himself with a measure of poise. Stiffly reading his speech off a piece of paper while the other Beach Boys stood around him, he spoke about the group’s origins in 1961, and how music can make people “happier, stronger and kinder.”

By the time Mike Love took his turn at the microphone, he was alone. The other Beach Boys had stepped away—perhaps for a photo-op—and Mike literally had the spotlight to himself. He used the opportunity to pick up where Brian had left off, on a positive note. Speaking extemporaneously, he began by discussing the element of harmony in the Beach Boys’ music, and its enduring appeal. This naturally led him to the subject of disharmony, at which point his remarks mutated into sarcasm, abrasiveness and resentment. In an apparent effort to say something about priorities and global perspective, he shot from the hip, and ended up betraying—at least as of that moment in 1988—a bitter and defensive contempt for the Beach Boys’ presumed competitors in rock ‘n’ roll, and dissatisfaction with his position in the business itself. He wanted to stress harmony and positivity, but couldn’t pull it off.

The most interesting part of Mike’s speech occurred when his stream of consciousness steered him briefly to his father, and then his mother and her side of the family. That is the side Mike shares with his cousin Brian Wilson and Brian’s now-deceased brothers, Beach Boys Dennis and Carl Wilson. While Brian’s speech flagged 1961 as the year it all began for the Beach Boys, Mike reached back another generation or two to the people he referred to as “Kansas Dustbowl Swedes,” who had emigrated to Southern California from the Midwest in the earlier part of the twentieth century. When they arrived in California in the 1920s, these people were short on money and essentially homeless. So, as Mike Love made a point of stating that night at the Hall of Fame, they lived in a tent on the beach. In practical terms, that beach is where the story of the Beach Boys begins.

The most detailed publicly-accessible source of information about the Beach Boys’ family history is the 1994 book The Nearest Faraway Place, written and researched by the late Timothy White. White reports that the common set of grandparents Mike Love shared with Brian, Dennis and Carl Wilson were named Buddy and Edith Wilson. They lived in Kansas. Like his father, Buddy was a plumber by trade, although members of the family had apparently taken a stab at farming in California years before, growing fruit and transporting it back by rail to be sold in Kansas. That didn’t pan out, and as of 1914, the year Buddy and Edith were married, Kansas remained home.

About nine months after the marriage, Buddy and Edith’s first child was born. Their third, Murry, was born in 1917, and the fourth, a daughter named Emily Glee, arrived in 1919. More would follow in later years. A restless man, Buddy was often away from home, on the road, traveling back and forth between California and Kansas. Though he may have been something of an absentee father in these years, he does not appear to have been running from or abandoning his young family. He was instead searching for a different locale in which to put roots down.

Notwithstanding Mike Love’s characterization of his migrant ancestors as “Dustbowl Swedes,” they did not come to California fleeing environmental catastrophe or some other act of God. Nor was it a matter of being unable to earn a living wage in Kansas, for Buddy Wilson was a skilled worker and employment was available working alongside (that is, for) his father in the family plumbing business. Maybe it was a matter of seeking increased wealth, or California’s friendlier climate, or plain, youthful wanderlust. Whatever it was Buddy wanted, the prospect of attaining it out in California outweighed what he had in Kansas where, as Timothy White reports, he had grown “resentful” of his “headstrong” father. In any event, as White tells the story, Buddy wanted out.

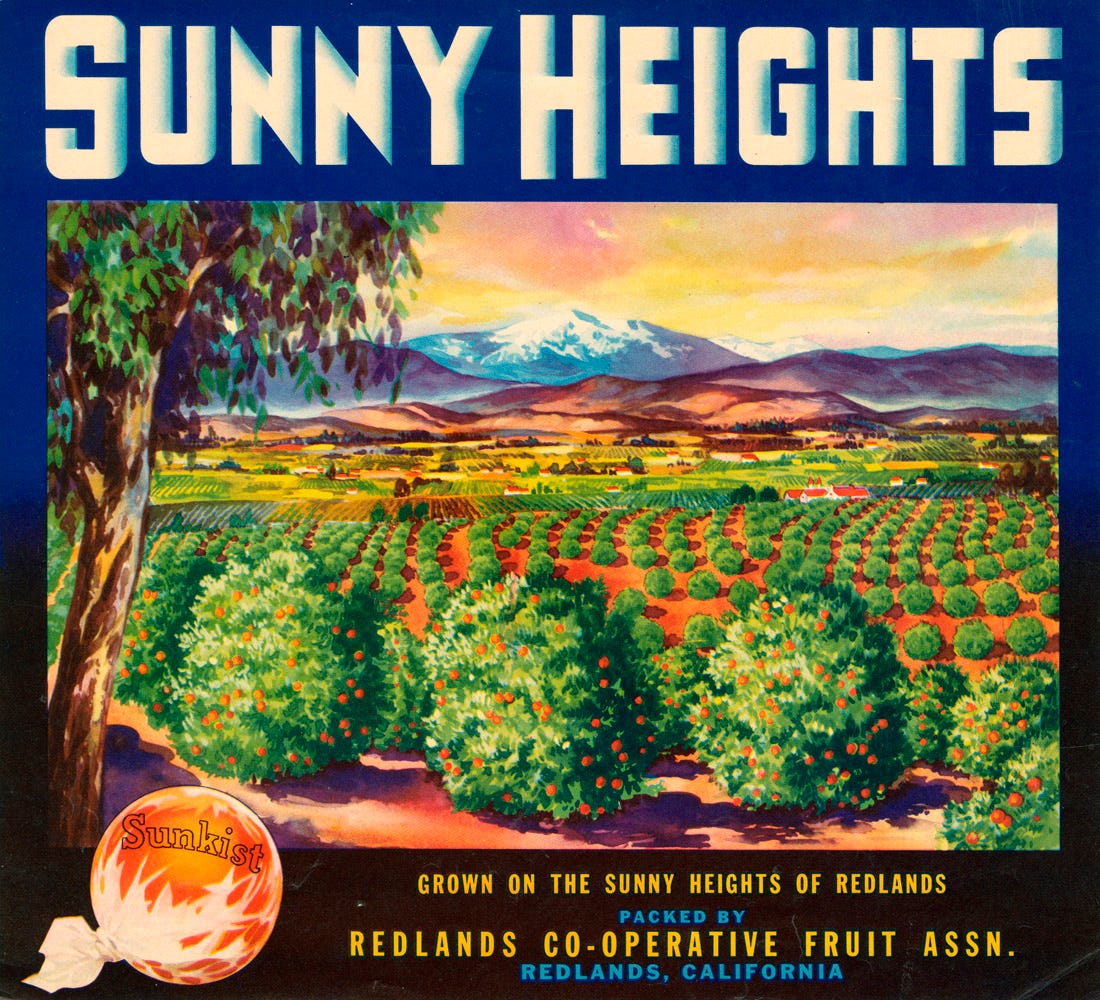

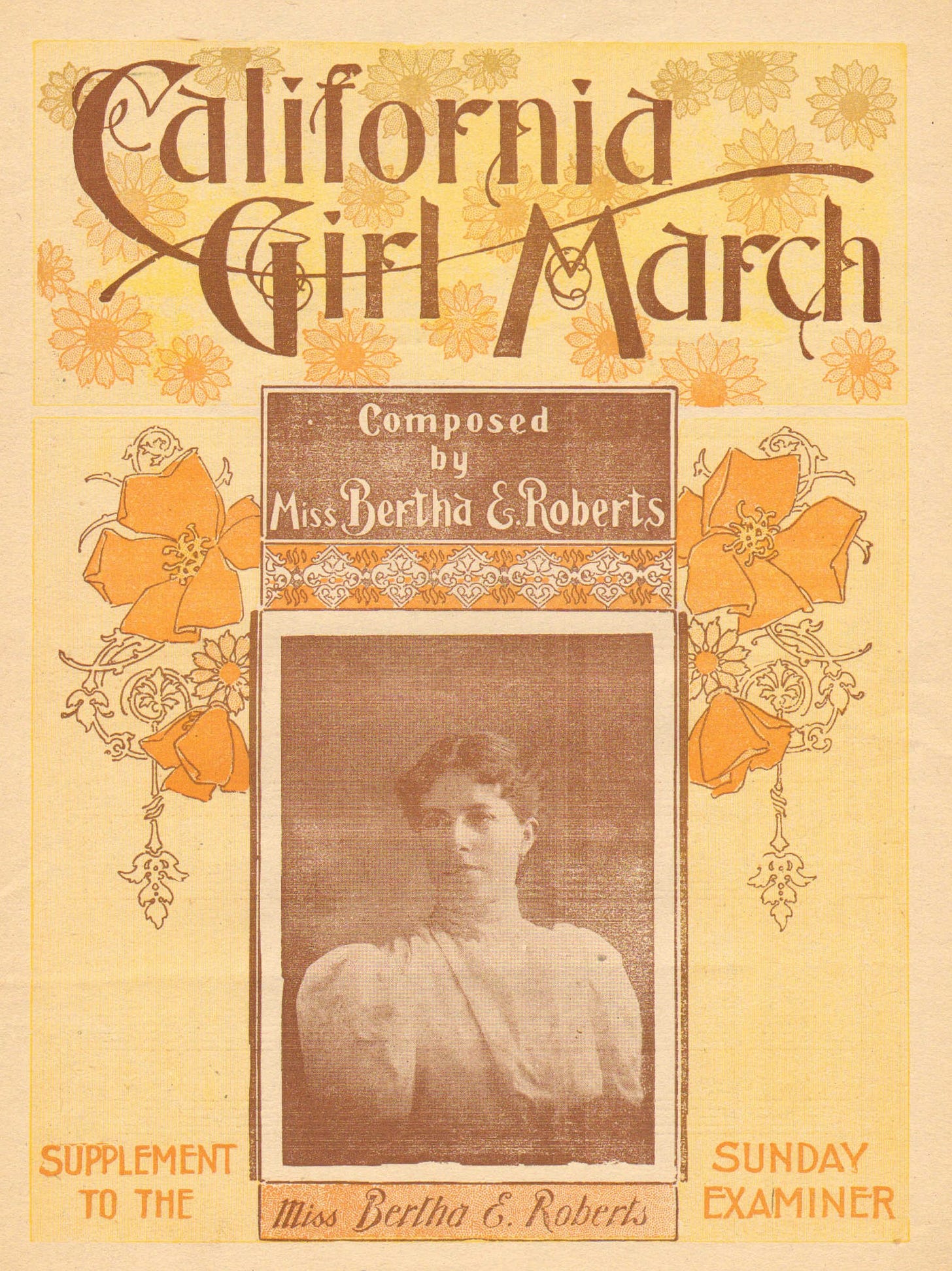

In those days, Southern California was wide open—vast and underpopulated, with much of the region, including the City of Los Angeles, covered by farmland. The local business powers (land owners, railroad magnates), who had arrived and prospered in previous decades, sought to inform the American public that opportunity awaited out West. The Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce opened satellite offices in the Midwest; newspaper advertisements and highway billboards in other parts of the country heralded the warm promise of Southern California; alluring artwork was affixed to the wooden packing crates that carried produce from California to points East. There was music too. Tourists, retirees, and prospective migrants learned about Southern California through songs about the region, whose sheet music often featured idealized imagery—Spanish mission-style architecture, orange groves, prototypical California Girls, and the locomotives and railroad cars that served as the means to get there and have it all.

In the early 1920s, Buddy Wilson was again scouting around in California; he at last sent word back home instructing the family to pack up and travel west to join him permanently. Edith and her kids then joined the great Midwestern migration of the era, departing by rail on the Santa Fe line and disembarking at Cardiff-by-the-Sea, a quiet seaside stop in San Diego County. There they discovered that they indeed were not in Kansas anymore, for here was the Pacific Ocean, and the beach (immediately adjacent to the “Swami’s” point-break that the Beach Boys would name-check in “Surfin’ U.S.A.”) where the family would live for a few weeks before finding permanent housing.

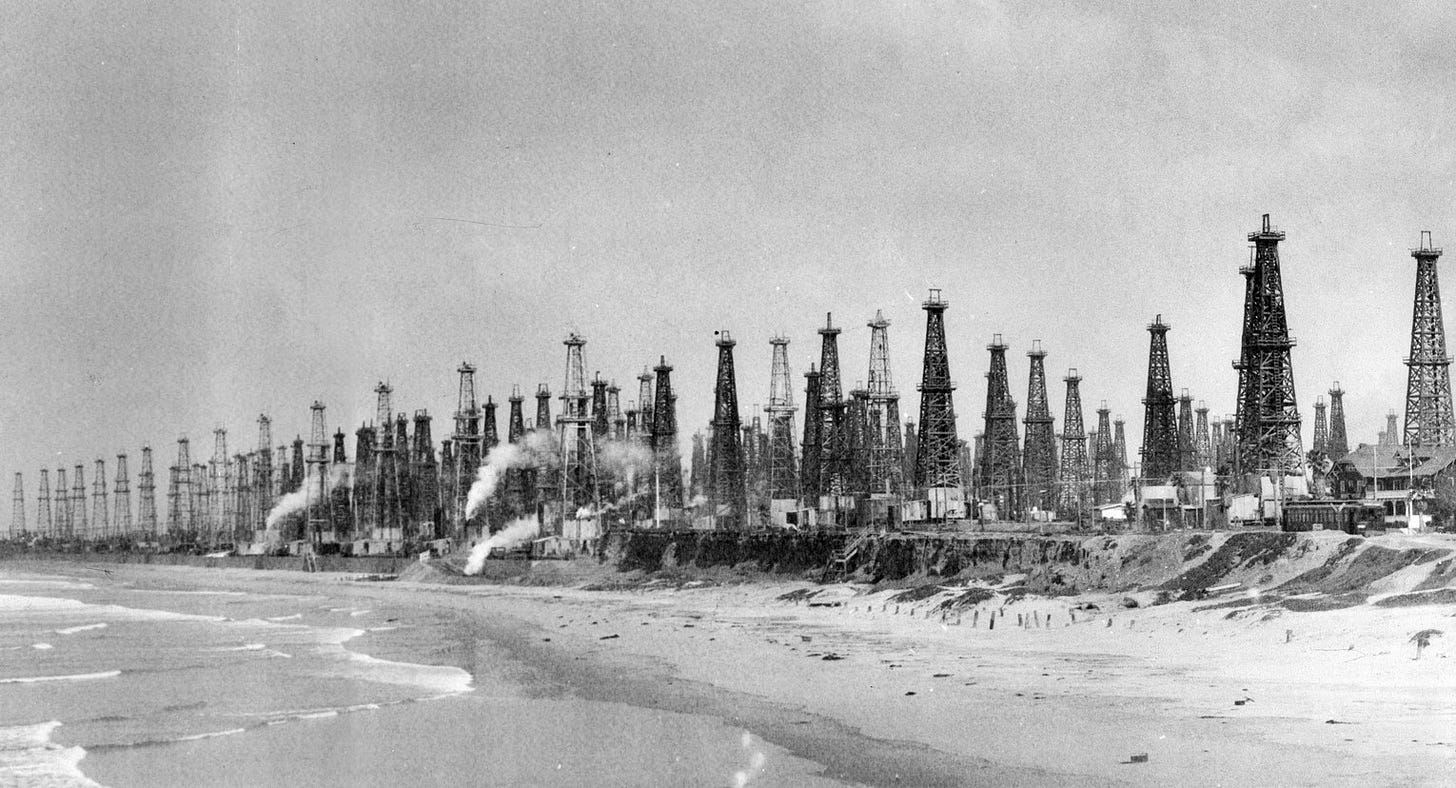

The Midwestern folk who migrated to Southern California in the early twentieth century had been enticed by scenes of blossoming orange groves stretching out below the distant, snow-capped San Gabriel Mountains. The Los Angeles business boosters had been sure to craft the most idyllic image of the region as possible. Prosperity, peace of mind and the finer things were within reach, all to be enjoyed while living in a temperate climate. Earthquakes were de-emphasized (or denied outright as a geological impossibility in Los Angeles) as was the fact that oil had been struck in the 1890s. In fact, by the time the Wilsons settled in Southern California the region was in the midst of an oil boom, rapidly evolving from sun-kissed agriculture to the grit and grime of hard industry. So, having made the decision to extricate himself and his family from Kansas, Buddy found himself amongst the legion of men drilling wells at the Huntington Beach oil fields. He was therefore separated from the family for days at a time. In his book, Timothy White wrote of the life-threatening nature of the work as well as the sordid and violent culture that developed within the boomtown ecosystem.

The family would soon migrate north, eventually settling in the humble, residential borderlands where the City of Los Angeles gives way to smaller incorporated communities like Torrance, Inglewood and Hawthorne. Buddy’s oil-work didn’t last long; steady full-time employment didn’t come easily for him. His restiveness impelled him to skip from job to job, including a stint up in the Eastern Sierra as a transient worker repairing the infamous L.A. City pipelines that had been sabotaged in the water wars. To pick up the slack, Edith also worked outside the home, as did the kids when they were old enough. Everybody worked, but there was still time for some leisure activity, including trips to the nearby L.A. County beaches and music in the home: guitar, piano and singing.

Life in the Wilson home was violent. Family recollections, as filtered and transmitted through various sources, include savage beatings Buddy laid on his sons, particularly Murry. Nobody has ever suggested that Emily Glee or the other daughters ever received this sort of treatment, but if the girls were spared the various forms of physical brutality, they were nevertheless forced to witness it, and often. According to Timothy White’s research, the violence was “chronic,” meaning that it occurred time and time again, and therefore became part of workaday life in the Wilson home.

And if this wasn’t bad enough, all the children, boys and girls alike, watched as their father also went after their mother. This was an outrage. More than anything else, it was Buddy’s treatment of Edith that would earn him the enduring enmity of his children. In a courageous gesture of love and devotion to his mother, Murry often battled his father, physically, to shield her from attack, a task White correctly describes as “ghastly.” Murry received merciless treatment in return. One account has his father retaliating with a baseball bat. Nevertheless a young and stalwart Murry did what was necessary to support his family—to keep it together. After graduating from high school in the mid-1930s, he secured full-time work (in the midst of the Great Depression) and brought his paycheck back to the home of his parents, with whom he continued to live. Brian Wilson would later learn of an incident that would have occurred during this time, in which 19-year-old Murry again physically intercedes to protect his mother, only to be subsequently ambushed in his bedroom by his father who—then in his mid-forties—used a lead pipe to nearly hack off one of Murry’s ears.

The good news for Murry was that somewhere along the line he had met a girl named Audree. They wed in 1938, when they were both 20 years old. Murry and Audree moved into their own place after they wed. They surely married for the right reasons—to give and receive love—although for Murry at least, marriage may have also helped extricate him from the oppressive circumstances of his family life—a common-enough pattern that Brian Wilson would address in subtle, digestible form with Beach Boys songs such as “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” and “We’ll Run Away.” That same year Murry’s younger sister Emily Glee also married, to a young man named Milton Love.

While their parents had conceived their first child around the time of their wedding, for whatever reason Murry, Emily Glee and their respective spouses waited longer to have their first. Murry and Audree lived together as childless newlyweds for about 3 ½ years before conceiving their first child, Brian, who was born in June 1942. Dennis Wilson was born in 1944, and youngest child Carl Wilson followed in 1946. Mike Love, born in 1941, was the first of Glee and Milton’s children.

To be continued in Part 2 of A History of Brian Wilson

Selected References for Part 1

“Beach Boys accept award Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductions 1988.” At YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oZSAQX2uuUY

Bowman, Lynn. Los Angeles: Epic of a City. Berkeley: Howell-North Books, 1974.

Gaines, Steven. Heroes and Villains: The True Story of the Beach Boys. New York: Signet/New American Library, 1986.

Kun, Josh. Songs in the Key of Los Angeles. Santa Monica, CA: Angel City Press, 2013.

Starr, Kevin. Material Dreams: Southern California Through the 1920s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

White, Timothy. The Nearest Faraway Place: Brian Wilson, the Beach Boys and the Southern California Experience. New York: Henry Holt, 1994.

Zimmerman, Tom. Paradise Promoted: The Booster Campaign that Created Los Angeles 1870-1930. Santa Monica, CA: Angel City Press, 2008.